| ||

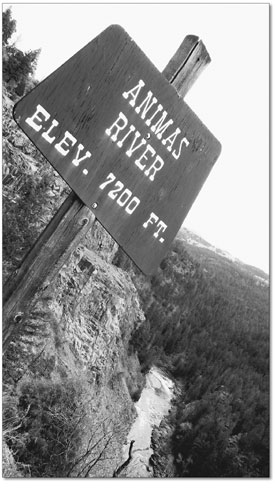

| The quest for Wild and Scenic Effort to protect local rivers moves on several fronts SideStory: Animas River Days flows back into town

by Will Sands Dozens of pristine rivers and creeks flow through the San Juan Mountains, but the prestigious National Wild and Scenic River designation has somehow eluded Southwest Colorado. That may change. Work is now under way on multiple levels to determine if any local waterway is suitably “Wild and Scenic” to merit designation and preservation. In 1968, the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act was signed into law and proclaimed that select rivers and streams should be preserved “in their free-flowing condition to protect the water quality of such rivers and to fulfill other vital national conservation purposes.” The Wild and Scenic Rivers Act has accomplished this goal in some places; forty-seven rivers and streams have been designated and preserved in Oregon alone. Colorado, on the other hand, has but one Wild and Scenic River. After years of negotiations, controversy and in-fighting, the Cache la Poudre River, which flows from its Rocky Mountain National Park headwaters down through Fort Collins, was designated in the mid-1980s. Colorado’s poor record is destined to change, however, and a river in the San Juan Mountains could become the state’s second Wild and Scenic River. The San Juan Public Lands Center is currently revising its management plans and considering which local rivers could be designated as Wild and Scenic. To do this, the Forest Service has looked at the “outstandingly remarkable values” of all of the region’s rivers and streams. These values can be biological, recreational, geologic or archeological. Last year, the agency short-listed dozens of creeks and rivers in the region that have one or more “outstandingly remarkable” value. On the list was everything from the entire Animas and Piedra rivers to the water-deprived Lower Dolores to obscure creeks like Cinnamon, Deer Park and Molas. Currently, the agency is considering “suitability,” a more subjective value related to social needs and constraints. Kay Zillich, a hydrologist with San Juan Public Lands, commented, “From the list of eligible streams, we’re trying to pick out rivers and creeks that are ‘suitable.’ Suitability deals more with the combined social values of a river. For example, maybe the development potential of a stream and its contribution to society outweighs its value as a Wild and Scenic river.” The San Juan Public Lands Center is not alone in the search for Wild and Scenic. A local stakeholders group has formed and is also considering the values of local rivers and streams. Known simply as “The Rivers Work Group,” the broad cross-section of interests is attempting to bring the community into the Wild and Scenic discussion. “The effort is meant to create a forum so the community as a whole can discuss these rivers and discuss what it wants to do with the resource in the future,” said Chuck Wanner, water issues coordinator for San Juan Citizens Alliance. Wanner has a unique perspective on Wild and Scenic Rivers. As president of Preserve Our Poudre, he successfully lobbied for the Cache la Poudre’s designation nearly 20 years ago. Like the Poudre effort, Wanner said a broad stakeholders’ effort is the only hope for a local designation, and the Rivers Work Group represents a good start. In addition to SJCA, the collaborative effort includes representation from the San Juan Public Lands Center, the Colorado Water Conservation Board, the Nature Conservancy, the Southwest Water Conservation District, U.S. Congressman John Salazar and U.S. Senator Ken Salazar’s offices, the Southern Ute Indian Tribe and the Wilderness Support Center. “We’ve worked on a process for looking at rivers that starts with a sweep, which identifies all of the values on rivers,” Wanner said. “We’re also looking at consumptive values like agriculture or drinking water and nonconsumptive scenic or recreational values.” Unlike the San Juan Public Lands Center, the Rivers Work Group has already narrowed the list of potential candidates for Wild and Scenic designation. Hermosa and Vallecito creeks, the East and West Forks of the San Juan, and the Animas, Pine and Piedra rivers have all made the cut. Whether they are deemed suitable is another issue. “Suitability is determined by social and economic factors,” Wanner said. “The question is, ‘Does it make sense to designate a Wild and Scenic river from the perspective of the community and the resource?’” The San Juan Public Lands Center has pledged to consider all user angles as it moves toward releasing a draft environmental impact statement this September. That draft will eventually give way to a final document, and then one of the Salazar brothers would have to take the matter before Congress. “I think it will be a long process,” Zillich commented. “But I think there are some people ho are interested and have the energy to put into it.” Designation or no designation, Southwest Colorado’s rivers and streams will benefit from the process. The Rivers Work Group is taking a holistic approach to each of the rivers and looking at what can be done to protect them regardless of Wild and Scenic status. “The group is looking at a number of ways other than Wild and Scenic designation to protect these streams,” Wanner said. “We’re also looking at each of the rivers as a whole rather than at just the eligible sections.” From the Forest Service perspective, potential designation may be as helpful as actual Wild and Scenic status, a turn that could prevent damage to the watershed over the short term. “Our job is figuring out which rivers have the best chances,” Zillich concluded. “Then we’ll manage them suitably and preserve those outstandingly remarkable values until the other processes kick in.” •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel