| ||

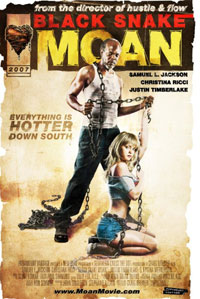

The Lazarus phenomenon by Judith Reynolds When old man Lazarus takes his garbage out in the morning, he unexpectedly sees a body nearby. During the night, someone dumped human garbage on the dirt road near the old man’s house. Lazarus, dead to the world after his wife has left him, rescues a badly beaten teen-age girl and takes it upon himself to bring her back to life. If this sounds faintly Biblical, it is. “Black Snake Moan” is a bizarre fable of betrayal and redemption – obliquely related to the story of Lazarus in John 11:41-44. Here the story is told with a double shot of Southern discomfort. Written and directed by Craig Brewer, the film follows his two other features that have the equally strong themes of frailty and forgiveness: “The Poor & Hungry” and the Sundance award-winner “Hustle & Flow.” The story of “Black Snake Moan” is set in contemporary, rural Tennessee. But before you get to it, there’s a long pre-title sequence. Director Brewer signals the mythic nature of the tale by framing it with an old device – a storyteller. At rise we see the Delta Blues pioneer Son House in a crackly old, black-and-white archival film. “I’m talkin’ bout the blues,” he says, “not monkey junk. There is only one kind of blues that counts. lt’s about the male and the female.” Then in a quick series of cross-cut scenes, we are introduced to the two main characters: Lazarus (Samuel L. Jackson) and Rae (Christina Ricci). Each has been or will be cast adrift by a lover. Lazarus has been abandoned by his wife in a particularly nasty trade off – she’s gone over to his younger brother. Did I say Biblical? Rae loves her boyfriend Ronnie (Justin Timberlake), but as soon as he leaves for boot camp, and presumably Iraq, her true nature emerges. Rae is a wild child, the daughter of neglect and abuse, and known as the town slut. Act One essentially reveals how Rae and Lazarus deal with their abandonment. It’s enough to say both are self destructive. Their lives intertwine on that dirt road where Lazarus puts his weekly garbage. As implausible as the rescue seems, you simply have to accept it as part of the fable. Lazarus is inspired to care for the broken girl and gradually brings her back from serious injury and searing fever.

Then the film takes another imaginative leap; Rae’s feral temperament and repeated escape attempts prompt Lazarus to make her a hostage. Suddenly you’re at the edge of both fantasy and soft porn, an edge the writer-director exploits. Scenes with chains and a scantily clad Ricci have more than a whiff of sadomasochism. Once in the air, they hover over the border of good judgment. It’s worth a debate. (The film would be an interesting choice for the Abbey’s Chick Flick night, sure to ignite discussion). The film is structured like a classic tragedy. The storyteller returns toward the end to remind you of the film’s mythic grounding. Full blackouts stop the action at Act I, II and III intervals. The blackouts enable the director to resume the story with a new tone in a new setting. And like all great tragedies, things get hairy just before the end. Be prepared for an up tick in sound and action. More I will not say. Fables are full of both fantasy and exaggeration, something worth remembering. All I’ll say is that the movie doesn’t fall into a pit it can’t get out of. While Jackson, Ricci and other actors (John Cothran Jr., S. Epatha Merkerson, Michael Raymond-James) execute their roles well to create a believable universe, that can’t be said for Justin Timberlake. He plays Rae’s boot camp boyfriend. Apparently, the pop singer is trying to make a transition into acting. Even though he’s presumably making four films in 2007, he’s wooden and doesn’t seem to have the instincts to slip under the skin of a character. Timberlake tries to make something of the anxiety-ridden Ronnie, who leaves early but returns and punches up the drama later. But ultimately, he fails to bring the bewildered boy alive. The film title comes from a song written by Blind Lemon Jefferson. It refers to the enveloping darkness of the blind as if it were a snake slithering into a room. Filled with fear, the song holds a central place in the film. Part of Lazarus’ symbolic death-via- depression is that the old man has stopped playing his beloved guitar and singing the blues. The rescue of a wounded child-woman brings out his innate tenderness as well as his various guitars. Momentarily, the plot point seems gratuitous – another detail to let be. Jackson does a more than credible job of singing and pretending to play the guitar; the camera carefully crops out his hands as he sings. “Black Snake Moan” is a metaphor, of course, for the blues and has in it a reminder that many a man, Winston Churchill for one, or woman has referred to depression as a black snake or a black dog. •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel