|

| ||

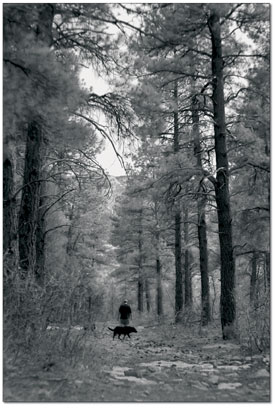

| Balancing trails and trees

by Will Sands Efforts to eliminate wildfire are increasingly stepping into Durango’s back yard. As a result, forest thinning and recreation are also meeting head-on on the outskirts of the city. With logging currently taking place on the popular Log Chutes trails and plans forming to log Animas Mountain this summer, the Forest Service is doing its best to balance forest safety and user concerns. In the summer of 2002, 15,770 separate wildfires burned more that 1.2 million acres throughout the West. Among the blazes was Durango’s devastating Missionary Ridge fire, which charred nearly 71,000 acres north of town and claimed 56 homes. In 2003, the Bush administration responded with the Healthy Forests Restoration Act and the National Fire Plan was born. Among the plan’s mandates is that the Forest Service thin trees in the Wildland Urban Interface, the edge of the forest in proximity to communities and homes. “The danger is obviously having big fire years like we had in 2002, 2004 and 2006,” explained Pam Wilson, fire information officer for the San Juan National Forest. “Because of excessive drought and fuels buildup we have some areas on the forest that are increasingly in danger. In addition, more people are building right on the edge or within the forest.” Since 1990, nearly 135,000 acres of San Juan Forest and 24,000 acres of Bureau of Land Management lands in the vicinity of Durango have been treated. The local Forest Service uses three approaches to curbing fire threat – prescribed burning, hand thinning and a relatively new practice known as hydromowing, where a large spinning drum with carbide teeth eliminates small trees and brush. “Hydromowing is a fairly cost-effective way to treat a lot of acres,” Wilson explained. “Hand thinning is very, very expensive and prescribed burning has been marginal since we’ve been in this drought and overall fire danger has been so high.” Some conflicts have arisen because of these fire mitigation efforts, however. The Wildland Urban Interface is also an area popular with local trail users, and last summer, a fuels mitigation effort north of Durango in Hidden Valley raised objections. In addition, the Forest Service is currently logging and hydromowing a portion of the Log Chutes trail system. As a result, portions of the trail will be turned back into logging roads and temporarily closed. Wilson argues that the Forest Service is doing its best to maintain recreation resources while addressing threats to public safety. “We did our best to work very closely with user groups on the Hidden Valley project, and we tried to keep most of the work between the trails and worked during slower times of the year,” Wilson said. “With Log Chutes, there was an understanding that someday there would be changes to those trails. There could be some temporary closures there and we do plan to rehabilitate the trails when the work is done.” The most controversial project may still be on the horizon, however. San Juan Public Lands plans to treat the upper portions of Animas Mountain, located immediately north of Durango, this summer. Though the details remain vague, there is a chance portions of the popular trail could be turned back into roads so hydromowers can be used. Wilson said that the BLM will explain the details of the project to a group of stakeholders next Monday. Among the stakeholders that will be present Monday is the trails advocacy group, Trails 2000. Mary Monroe, the group’s director, commented that it is crucial for users to raise their concerns and interests prior to the beginning of the project. “One issue is that it’s hard for people to visualize the impact of a fuels project until they actually see the degradation of a trail,” she said. “It’s before we see the impacts to the trails that we need to come up with plans to reduce those impacts.” That said, Monroe acknowledged that the Forest Service and the BLM do their best to address public concerns, but she stressed that the local trail network is also a public resource that needs to be preserved. “I think the Forest Service and BLM understand that figuring out fuels mitigation in the urban interface is a fine balance,” she said. “There are lots of homes as well as a great deal of recreation. I feel that it’s my job to remind them about the importance of trails, particularly to this county, as these projects go forward.” The conservation group, San Juan Citizens Alliance, will also be present at the coming stakeholders meeting. On the one hand, Amber Clark, public lands coordinator for the alliance, said she appreciates the need for fire mitigation in the interface. On the other, she added that particular care must be taken in a widely used and popular area like Animas Mountain. “In general, we think the appropriate place for fuels mitigation projects to occur is close to communities, because that’s where the greatest danger is,” Clark said. “We definitely plan to learn more about the proposed project on Animas Mountain because it is so widely used and there will probably be a number of concerns.” Courtesy of the National Fire Plan, thinning projects are often “categorically excluded” from environmental review and exempt from public comment. Clark commented that she is also concerned by that trend. “I does seem like there are a lot of fuels projects that go through the process quickly,” she said. “We hope the Animas Mountain project will be available to public so there aren’t any surprises down the road.” Like San Juan Citizens Alliance, the conservation group Colorado Wild favors fire mitigation in the Wildland Urban Interface. “The most important issue is protecting communities, homes and infrastructure from fire,” said Ryan Demmy Bidwell, Colorado Wild’s executive director. “Research on fire protection shows that treatment is most effective in the first 100 feet of so immediately surrounding homes.” However, Bidwell also urged the Forest Service and BLM to be inclusive and engage the public on the Animas Mountain project. “Particularly on a project that has the potential to be controversial like Animas Mountain, it makes sense for the Forest Service to engage the public, bring people to the table and resolve any concerns before the project begins,” he said. Wilson argued that the agencies are doing their best to do just that, and Monday’s stakeholders meeting is evidence. “It’s a balancing act, and I know it takes a little getting used to for people, but we’re trying very hard to keep everyone happy,” she said. “It’s one of the reasons we’re bringing groups together when we present our plans for Animas Mountain.” Wilson then added that scorched ground and burned forest and homes remain the agency’s biggest concern, saying, “I would hope people would want to protect these trails and continuing using them rather than go hiking through areas that are filled with a bunch of ash and black sticks.” •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel