| ||

| The persistence of drought Study suggests that driest times lie ahead SideStory: A regional approach to global warming: 5 Western states agree to cut greenhouse gases

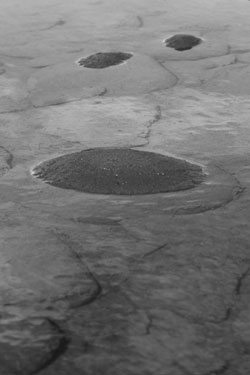

by Will Sands Tree rings along the Colorado River have a strong message to share – the Southwest is more prone to drought than was widely believed. In a recent report, the National Research Council revealed that protracted droughts are historic and common occurrences for the region. Plus, the group is also sending a strong message to the region’s water users – “Be prepared.” Future droughts look to be longer and more severe because of a regional warming trend that shows no signs of dissipating, Drawing water from the Rockies through tributaries like the Animas River, the Colorado River is a resource for tens of millions of Americans as it draws water from the Rockies. Southwest residents use the water for drinking and other household uses along with agriculture, hydroelectric power and recreation. The river also is home to diverse ecological habitats. For these reasons, exceptionally dry conditions in much of the Colorado River Basin in recent years are cause for concern, and in response the Research Council convened a committee to examine how climatic trends might affect the river’s future flows. With this study, the group departed from the conventional examination of stream gages, opting instead for a deeper historic context via tree ring data. The new information is telling, showing that the Colorado River traditionally shifts into decades-long periods where the flows can be below average. While some may argue that the findings downplay the effects of global warming, the report disagrees. The tree-ring data, coupled with temperature trends and projections, suggest that extended droughts will recur and may be more severe than recent dry spells. “The report doesn’t downplay global warming, it complicates it,” explained Kelly Redmond, one of the study’s authors and the deputy director of the Western Regional Climate Center. “It’s a little hard to know exactly what to expect from climate change, but we have much more confidence in increasing temperatures than anything else.” Many different climate models point to a warmer future for the Colorado River region, according to Redmond. Projections of future precipitation are more uncertain and if anything, warmer temperatures are moving peak run-off to earlier times in the year increasing water demand from downstream. “In the headwaters regions, the precipitation forecasts are actually for amounts not that different than they are today,” Redmond noted. “What matters is when that precipitation falls and melts. Winter snowfall is much more valuable to the watershed than spring rain.” Based on the evidence, the report suggests that rising temperatures will ultimately reduce flows in the Colorado and its tributaries and drop stored water supplies. Rapid population growth throughout the Southwest further exacerbates the situation. “This should not be surprising for people, but there is a looming collision between increased demands on the river and changes in the way water is being used,” Redmond said. “Cities are now driving more of what’s happening in the West. Unlike agriculture, cities cannot lay fallow during dry years. The demand is not very flexible.” Curiously, the tree ring data also made for another disturbing revelation, showing that the years between 1905 and 1920 were exceptionally wet. This is significant because the Colorado River Compact – the document governing the allocation between upper basin and lower basin states – was signed in 1922. Population across the Southwestern states has also grown rapidly in recent decades. Since 1990, Colorado’s population has risen by 30 percent. Arizona saw a roughly 40 percent rise during the same period. Plus, consumption is going up dramatically as evidenced by a doubling of water use in Las Vegas between 1985 and 2000. The combination of limited water supplies, rapidly increasing populations, warmer temperatures and the likelihood of recurrent drought point to the need for conservation. “We are urging that more attention be paid to the demand side of this equation,” Redmond said. “If we can lighten our demand on the river, we can buy ourselves some time while we come up with real solutions and start looking at the river more wholistically.” The committee is calling for a collaborative, comprehensive basin-wide study of urban water practices and pressing issues in water supply and demand. The hope is that this information can be used in preparing action-oriented water planning, and that collaborative efforts could aid in better communication between federal agencies, states and municipalities. Redmond concluded that as another drought summer takes shape in the greater Colorado River Basin, the message should be clear. All water users need to start taking action immediately. “The fact that we may be in for one more drought year emphasizes the need to start finding solutions,” he said. “We only have so much more wiggle room on this issue.” • The complete Colorado River Basin Water Management report is available online at http: //books.nap.edu/catalog/11857.html.

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel