| ||

Getting on the horse

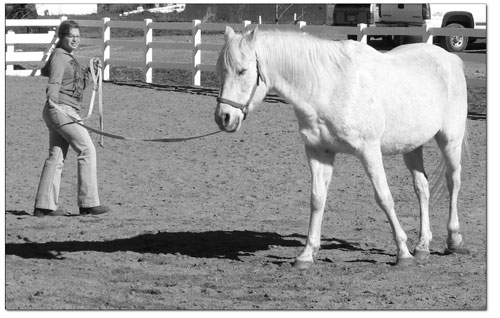

by Shawna Bethell At an arena just off East Animas Road, a female high school student with sandy blonde hair walks a horse around bright orange cones and through a maze of pipes. She then turns to the maple-colored quarter horse that looms over her and attempts to coax him backwards. He refuses to move. Again and again, she meets the determination of the large animal before tears come, and the two women standing beside her step forward. They ask her questions about her frustration, about the problem before her, about her options. After a deep breath and a nod, the girl turns back to the horse and starts again. He steps gingerly backward at her touch. Anyone remembering those agonizing years of adolescence can recall how it felt to not quite fit, to be unsure of your talents, to not know how to ask for what you needed, and to not know what to do with the frustrations that developed from those experiences. Luckily for Durango youth, the Mancos-based Medicine Horse Center now offers its Circle of Healing Foal Project to the local community. This new therapeutic program teams troubled adolescents with horses, and teaches the youth – through horsemanship classes – how to communicate, problem solve, ask for help and control their anger. It is hoped that as students master these life skills, their self-esteem increases and they are able to utilize these new abilities in other areas of their lives. “This program has been a blessing,” said one mother of a participant in the Medicine Horse program. “My daughter and I are communicating better than we ever have. The horse’s energy just evokes a sense of calm, and the exercises bring forth a strength in her she didn’t know she was capable of.” Lynne Howarth, director of Medicine Horse, explains the concept of the program, saying, “It is not about riding. It is about relationships and socialization. Many of our kids are so plugged in that they don’t know how to interact; they don’t have to. This program is experiential. It is a place for them to be accepted for who they are, a place for them to learn to relate to others.” Trish Lemke, program director, sees the support that a group like Medicine Horse can provide. “It’s as though the horse is the catalyst. When we sit in group, no one wants to say anything about what’s happening, but one person might say she was afraid to ride a horse, then everyone starts talking, and we take that subject of overcoming fear and apply it to other areas.” In Medicine Horse’s “Circle of Healing Foal Project,” a “team” works together, made up of the student, the therapist, the horse trainer and the horse (which often is the deciding factor.) The student learns to work with the horse, getting it to maneuver through a course, learning to ride it, etc. As the student faces difficulty, the therapist steps in to discuss anger-management or problem-solving techniques while the horse trainer reads the horse’s behavior and body language. The student learns and hopefully takes those lessons to school or other scenarios where he or she is less confident. “Horses are a great equalizer,” said Howarth. “They are big and powerful, yet they are gentle. You can’t force a horse; you can’t get angry and hit the horse; you can’t lie to a horse.” Howarth believes there is a particular energy of understanding that comes from horses, and she tells the story of Elvin, a show horse who was donated to the program after an injury, who was able read a young girl’s misery. “We had just finished the program, and the girls were sitting in a circle discussing the morning,” she says. “The horses were across the paddock. One girl just had a meltdown about what was happening in her family. Elvin walked up behind the girl, placed his hooves and legs directly against her back and leaned forward, his whole neck and head hanging down over her. He stood there until she was calm.” As Lemke explains, the program is not just for adolescent girls. However, most often, it is young women who need to learn to be assertive and increase their self-esteem, and who seem most drawn to the horses, she says. But the effect of the horses can be equally powerful on the boys, says Howarth. “Those big guys who come out from the high school may be the tough ones who have seen a lot of violence in their homes,” she says. “Pretty soon you will watch them take the horse off to a corner to have some time, and then you’ll see them hug the horse’s neck. The horse allows them to soften. There’s no judgment.” •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel