| ||

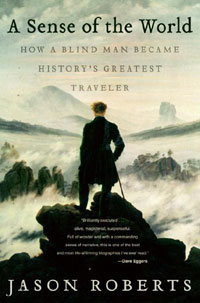

The blind traveler by Joe Foster A Sense of the World, by Jason Roberts. Harper Collins 2006. Biographies give me gas. There’s something about the whole genre that makes my skin crawl, and I can’t help but equate biography readers to the people who slow down next to a car accident hoping to see something gruesome. What, I wonder, is the appeal? There seems to be something fundamentally attractive about the fact that a story is based on actual events, while the truth of the matter is, most biographies contain as much fiction as any great novel. (In this train of thought, then, maybe all fiction is merely a biography of someone that has never existed.) Maybe the biography’s appeal is just reading about someone that did it, whatever that big “it” was in their life, they did it. They refused to settle comfortably into their mediocrity, but did something, or became somebody worth reading about. No small feat. Maybe we read such things as instruction manuals, a how-to-not-live-quietly mission statement. There are people that have done extraordinary things. One of these is a guy named James Holman. The author of this biography, Jason Roberts, saw references in a few texts about a man known simply as “The Blind Traveler.” After digging wherever biog

raphers dig for such information, probably libraries and stuff, he found that , James Holman, quietly and obscurely became the most widely traveled person in the world in the time span reaching from 1786 to 1857, and he didn’t get his nickname because he sold window coverings in Indonesia. He was blind, he traveled alone, usually without enough money, and he went farther longer than anyone else in history. He was imprisoned in Siberia, helped map the Australian outback, hunted rogue elephants (successfully) in the East Indies, trekked the Andes and circumnavigated the globe; all without prior knowledge or research about any of the countries he visited. Darwin and Sir Francis Bacon were amazed by him. But you’ve never heard of him. Why? Because of the very thing that made his life all the more awe-inspiring – his blindness. He wrote some pretty hefty books about his travels, meticulously documenting everything he experienced, but nobody really took him that seriously, insisting that he could never have really experienced what he did in any credible way because he couldn’t actually see his surroundings, to which Holman would reply, “I see better with my feet.” The book contains an anecdote that displays just how aware Holman was of his surroundings. He met two friends at a busy London restaurant. They arrived first and when he came in one whispered to the other to stay quiet to see if Holman could find them. Without pausing, he made his way through the restaurant, dodging bustling waiters, and set his hands on the shoulders of his friends, with an amused smile on his face. Shocked and impressed, they asked him how he knew where they were seated. He replied that he could hear them whispering as he came through the door. Throughout the book his abilities are repeatedly doubted, and he consistently and quietly amazes and converts those that seek to protect him from himself. The fact that James Holman died in obscurity is a heinous betrayal of a truly inspiring human being, which is probably the reason that A Sense of the World was a featured selection for the Civil Rights Book Club. I’ve read no other story that makes me feel as if I’m missing out on worlds of sensations because I’m so dependant on my eyesight. This is one of the only biographies I’ve read that didn’t have me reaching for the Bean-o. Pick it up and check it out, and get a look into the world through the senses of a man driven to experience everything our world could offer. •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel