|

| ||||||

| From neurosurgeon to photographer

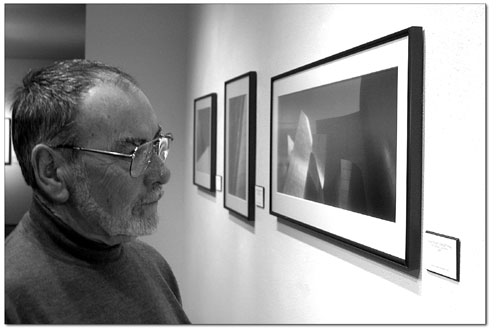

by Jules Masterjohn What do neurosurgery and photography have in common? For retired neurosurgeon Joel White, the similarity has to do with his approach to the endeavor. “I am never totally happy with the results,” he told me as we sipped coffee at the local photographer’s hang out, Durango Coffee Co. White is referring to his ever-present search for a better way: how could a surgical procedure have been conducted differently or in what other ways could a photographic image been printed to realize similar effect? When I suggested that perhaps this was a perfectionist tendency, he chuckled and offered that I was “very kind.” The description he prefers is “anal compulsive.” In a medical practitioner, either of these descriptions is a comforting attribute for a patient, indicating the kind of mental focus one wants in his or her physician. Paying very close attention to the details is a very good thing during brain surgery. As a photographer, White’s penchant for perfection is equally appreciated. White jokes that he took up neurosurgery as a profession to support his photography habit, which has been an obsession for more than half his life. A self-taught photographer, he was introduced to the medium by his father who was an “ardent amateur” and had a darkroom in their home. Since these early days, the photographic world has exploded with new technologies. Initially White was skeptical about the merits of the digital darkroom, aka the computer. He tells a story about attending a workshop presented by the publisher of a well-known photography magazine, Shutterbug. The workshop was a basic introduction to the use of Photoshop, computer software that allows for the creation and enhancement of images much in the same way that the traditional “wet” chemical process affords. At first skeptical, White’s dubiousness slowly broke, and he acknowledged that Photoshop could achieve results that were virtually impossible with the darkroom processes he had been using. White’s insatiable desire to learn drives him to continue photographing and furthering his expertise with the digital media. He has absorbed the new information with zeal. “The learning curve with Photoshop is nearly straight up,” he told me. Today, White not only has a traditional darkroom in his home, he also has a “dimroom,” as he calls it. This is the room where his computer and printer reside, with an ambient light level that is appropriately low to assist in accurate viewing light and dark values within images on his computer screen.

Regardless of the technical processes he utilizes in making his final photographs, he consistently employs a vocabulary that is foundational to the visual arts. Currently on display at the Fort Lewis College Art Gallery is “Shape, Line and Tone,” a selection of White’s black and white photographs taken over the last 30 years. As the title suggests, these pictures concern themselves with the aesthetic formal elements, showing the interplay of line, shape, light, value and texture, arranged to create phenomena like movement, balance, repetition and unity. While living in Los Angeles for 30 years before his relocation to Durango, White found satisfaction in photographing the urban landscape. He likes the shapes, lines and textures present in the structures produced by human civilizations. The wearing effects of human interaction on these buildings and streets – the decay, debris and destruction – all invited him to “get out and shoot.” In the pursuit of “things that life has made its make upon,” White has photographed places millennia old and those just born. From his “Dubrovnik Croatia,” an image of shadows cast upon a well-trodden stone-paved street, to “Tin Man,” a head shot of a giant replica of the Wizard of Oz character, to his architecturally based “Walt Disney Concert Hall” studies, White’s images capture more than the visual elements. Each photograph whispers – or shouts – of a past, present and future, reminding me of the unstoppable continuity in life. Though no humans are pictured, I can hear their presence. I hear the slow shuffle of aging feet upon the Dubrovnik road, a sound that has echoed, and will continue, for centuries. I hear children’s excited voices as they stand below a towering metal and silver fabric Tin Man, a reminder of the wonder that is held in every generation, by those young of heart. If I listen carefully, I can hear a crescendo in the ocean breeze’s melody playing off the curving architectural features of the concert hall’s roof. Please, don’t believe me – go listen for yourself.

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel