| ||

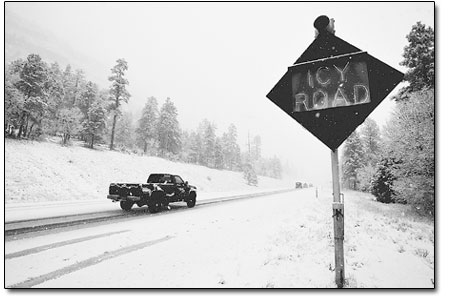

| A frightening forecast New findings spotlight increases in extreme storms and drought SideStory: A systemwide storm: Heavy snows hit nearly 20,000 electric customers

by Will Sands Violent and severe weather is increasingly making its way onto the weather map in Colorado and throughout the Rocky Mountain West. A recent study has linked global warming and a surge in extreme storms in Colorado. While some may hail the findings as cause for celebration, scientists are bracing for the worst. Climatologists, watchdogs and officials have been discussing the link between greenhouse gases and the frequency of major storms for years. With global temperatures increasing by an average of 1.1 degrees Fahrenheit over the last century, major storm cycles are also on the rise. The phenomenon has been especially significant for the Centennial State, according to a new report by the conservation group Environment Colorado. Violent storms in Colorado are up by 30 percent over only 60 years ago, according to the new study “When it Rains, it Pours: Global Warming and the Rising Frequency of Extreme Precipitation in the United States.” “At the rate we’re going, what was once the storm of the decade will soon seem like just another downpour,” said Keith Hay, energy advocate at Environment Colorado. For the report, analysts with Environment Colorado examined large rain and snow events through the continental United States between 1948 and 2006. The group filtered data from 3,000 different weather stations through a technique devised by the National Climatic Data Center and the Illinois State Water Survey. When complete, the study related a nationwide jump in extreme precipitation. It also pointed to a 25 percent increase in the frequency of extreme weather events in the Mountain West, and Colorado boasted one of the top increases in the nation, clocking in at a 30 percent growth in severe storms during the nearly 60-year test period. Taking an even closer look, “When it Rains, it Pours” cited an even more dramatic jump in Colorado’s high-desert regions. For example, it noted that storms with heavy precipitation had increased by a staggering 53 percent in the Grand Junction area. This heavy precipitation is most often coming as rainfall and that is not good news, according to Hay. “More frequent downpours, fueled by global warming, will hurt Colorado’s water quality and leave Colorado even more vulnerable to dangerous flooding in years to come,” he said. Similar conclusions were reached by none other than the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). In August of this year, NASA scientists put the finishing touches on a new climate model that points to violent storms and tornadoes becoming more common as Earth’s temperatures warm. Researchers Tony Del Genio, Mao-Sung Yao and Jeff Jonas established a link between warmer temperatures and “severe thunderstorms” in particular. They went on to predict that a warmer climate will make for more severe weather events but fewer storms overall. While many may view severe weather events as good news for the Rocky Mountains, Del Genio commented that the West is particularly threatened by the changes. He noted that few overall storms and more violent thunderstorms will lead directly to higher threats of wildfires. “These findings may seem to imply that fewer storms in the future will be good news for disastrous Western U.S. wildfires,” he said. “But drier conditions near the ground combined with higher lightning flash rates per storm may end up intensifying wildfire damage instead.” Higher temperatures and increased storm activity also mean more violent rainstorms and fewer snow showers, a phenomenon Durango residents have experienced firsthand in the last two weeks. A study earlier this year by the National Research Council looked at tree rings along the Colorado River that revealed a long history of drought in the Southwest. Fewer and more violent storms coupled with more rain and less snow could mean longer and more devastating droughts, according to the authors. “The report doesn’t downplay global warming, it complicates it,” explained Kelly Redmond, one of the study’s authors and the deputy director of the Western Regional Climate Center. “It’s a little hard to know exactly what to expect from climate change, but we have much more confidence in increasing temperatures than anything else.” Redmond added that future precipitation projections are becoming more uncertain and warmer temperatures are moving peak run-off to earlier times in the year and increasing downstream water demand. “In the headwaters regions, the precipitation forecasts are actually for amounts not that different than they are today,” Redmond noted. “What matters is when that precipitation falls and melts. Winter snowfall is much more valuable to the watershed than spring rain.” Both the National Research Council and Environment Colorado argue that the findings point toward a need for solutions. Redmond predicted a “looming collision” between reduced water supply and increasing population throughout the Southwest. With this in mind, he called for immediate conservation as a stop-gap measure. “We are urging that more attention be paid to the demand side of this equation,” he said. “If we can lighten our demand on the river, we can buy ourselves some time while we come up with real solutions and start looking at the river more holistically.” Environment Colorado took it one step further and suggested that reversing global warming is the “real” solution. Like Redmond, Hay noted that an increase in extreme thunderstorms does not mean more water will be available. Instead, scientists expect longer periods of dryness between the storms and increasing risks of protracted drought. “How serious this problem gets is largely within our control,” Hay said, “but only if we act boldly to reduce the pollution that fuels global warming.” The conservation group argued that the United States must reduce its total global warming emissions by at least 15 percent by 2020 and by at least 80 percent by 2050 in order to prevent the worst effects of global warming. The leap may seem daunting, but Hay concluded that it is actually well within grasp. “Steep reductions in global warming pollution are challenging but achievable,” he said, “and we already have the energy efficiency and renewable energy technologies we need to get started.” •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel