| ||

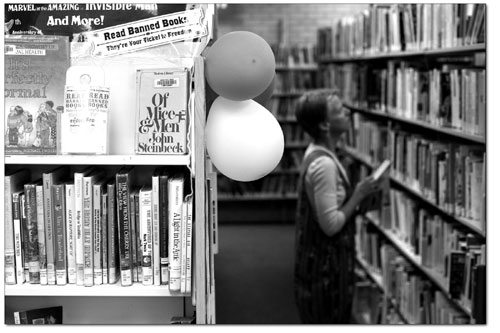

Challenging censorship

by Missy Votel Imagine a childhood without James and his giant peach or the adventures Huck Finn. Or a high school lit. course without Ralph and Piggy, Boo Radley or Holden Caulfield. Or a personal library devoid of Steinbeck, Morrison, Angelou or Vonnegut. Imagine a world without Harry Potter. If such things are unthinkable, think again. According to the American Library Association, books in author J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series were the most challenged in 2004-05, not to mention the most challenged so far this decade. The young sorcerer was in good company, followed closely by such stalwart classics as John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men and Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, not to mention some relative newcomers, such as Judy Bloom’s Forever and Captain Underpants, by Dav Pilkey. According to the nonprofit organization, there were more than 3,000 “challenges,” or attempts to remove or ban books, from schools and public libraries between 2000 and 2005. A challenge is a formal, written complaint filed with a library or school requesting that material be removed because of inappropriate content. The group released the list this week in conjunction with the 25th anniversary of Banned Books Week, Sept. 23-30, which it sponsors along with the American Booksellers Association and the Association of American Publishers, among others. For the crew at Maria’s Bookshop, the list, or topic of banned books in general, is nothing new. In fact, they point out, book burning is as old as Gutenberg himself, with Dante’s The Divine Comedy being burned in 1497 on religious grounds. “Basically, if a book has something to say beyond entertainment, it’s going to be challenged,” said Joe Foster, ordering manager for Maria’s. The downtown independent bookseller has been commemorating Banned Book Week with a display of endangered books for as long as owner Peter Schertz can remember. “We display books that have been either challenged or banned anywhere, either in a school or library,” said Schertz. And the titles gracing the display may be surprising, ranging from Dr. Seuss’ environmental tome The Lorax (banned in California for demonizing the logging industry) to Harper Lee’s Pulitzer Prize-winning civil rights commentary, To Kill a Mockingbird (banned for explicit language.) “It’s such an array of classics – To Kill a Mockingbird is one of the most profound criticisms of racism ever in print,” said Patrick Gaffey, senior bookseller for the store. However, despite the store’s annual participation in Banned Books Week, there are many people who are surprised to find out that such threats to intellectual freedom exist. “The conversations we have with customers … some are appalled at the books that have been banned,” said Foster. “They ask, ‘What year and what country?’ And we tell them, ‘This year, and this country.’” Perhaps the most notorious, recent case took place right in many patrons’ backyards in February 2005. In that incident, the superintendent of Norwood schools removed copies of Rudolf Anaya’s Bless Me Ultima, which was required reading in a high school class, following complaints from a parent. The superintendent, who admitted he never read the book in its entirety, referred to the book – a coming-of-age story about a young New Mexico boy and a traditional healer – as “garbage.” As the staff at Maria’s sees it, it is their role to mount a public awareness campaign, through the annual display, to alert people that such threats exist. “If the book of Chicano literature can be banned because it’s ‘trash,’ then it’s a good thing for booksellers and book-minded people to be aware of,” said Foster. The Durango Public Library also marks the week with a display of its own every year, said Adult Services Supervisor Paula LaFreniere. She said formal challenges at the Durango Library are rare. “I can’t recall one that is recent,” she said. Nevertheless, she said library patrons who are concerned with the appropriateness of a book have a formal avenue by which to voice their objections. “They can fill out a form that asks them specific questions about the book and what they found objectionable,” she said. From there, the complaint is looked over by the library’s director and staff members, who then decide whether or not to pull the book. If the plaintiff is not satisfied with the decision, he or she can appeal the decision to the Library Advisory Board for a final ruling, she said. LaFreniere said staff members are more likely to hear informal complaints at the circulation desk. “Sometimes, people just want to tell us how they feel about a book,” she said, adding that the library likes to get feedback. “We like to hear what people are worried about.” She said the library has a set of criteria it considers when selecting materials and tries to find items that meet various needs – something she reiterates when patrons voice concerns. “We express our philosophy on providing materials to the whole community,” she said. “While they may be offensive to some, they may be helpful to others.” Like Maria’s, LaFreniere said she also sees the library playing a role in public awareness. “Sometimes, people forget how good we have it,” she said. “But (book banning) could happen here.” School District 9-R Spokeswoman Deborah Uroda said there have been no recent efforts to challenge or ban books in the schools. Like the public library, there is a formal complaint process that parents can go through, which is then reviewed by several boards and ultimately decided by the school board, but such complaints are rare, she said. “We haven’t had anything go to that extent in a long, long time,” said Uroda, who hasn’t seen such a complaint in her seven years with the district. Like the public library, Uroda said most objections in the schools are handled on a more informal, case-by-case basis. Last year, she said there was an objection at Escalante Middle School to a scene in a Will Hobbs’ book, which was being read as a class assignment. A few years ago, a parent also voiced objections to a book in the high school library dealing with a gay teen-age boy’s decision to “come out.” She said in the case of the Will Hobbs book, the student was offered an alternative book to read. “We try to respect each parent’s view points,” she said. “Usually, once we have a dialogue, parents are willing to accept there is a diversity of opinions.” It is this diversity and freedom of choice that participants in Banned Book Week say they are trying to advance. Ultimately, LaFreniere, with the Durango Library, said the decision on what to read or not to read should be dictated by the individual, not others or the government. “We have many of the challenged and banned books on display. People should come and check them out and see for themselves,” she said. “It’s interesting to see not only what book was objected to, but why.” Gaffey, of Maria’s, borrows a quote from noted author and luminary Charles G. Bolte to drive his point home: “‘I fear more harm from everybody thinking alike than from some people thinking otherwise’ – to me, that’s the fundamental, bottom line.”

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel