| ||

| Taking on tamarisk Invasive tree begins to take root locally SideStory: The federal fight against tamarisk: Noxious tree bill awaits Senate’s approval

|

by Will Sands

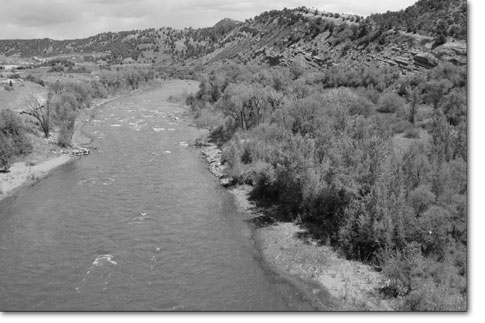

An unwelcome resident is beginning to settle in and take over the banks of the Animas River. Tamarisk, the “poster child” of non-native plants, is making a strong appearance locally. However, several local groups are intervening on the environment’s behalf and grappling with what amounts to a large-scale weed infestation.

Tamarisk, or salt cedar, is actually Eurasian in origin and has been sold by nurseries as a hardy, attractive, quick grower. A lack of natural predators make the trees a threat to everything around them, and left unchecked, they spread rampantly from front yards into river corridors and beyond.

The tenacious plant has already seeded itself all over the West, displacing 1.6 million acres of native vegetation. It also is estimated that each year the thirsty trees consume 2 to 4.5 million acre-feet of water from western rivers, water that could meet the needs of 20 million people or 1 million acres of irrigated farmland.

“Tamarisk outcompetes our native plants and takes habitat away from our bird species,” explained Dave Wegner, of the Friends of the Animas River. “It also outcompetes the native grass species and basically sterilizes the ground beneath it. Most significantly, tamarisk sucks up water like crazy.”

Tim Carlson, executive director of the Grand Junction-based Tamarisk Coalition, added, “The big issue is the drought in the West. Tamarisk has a well-deserved reputation for being thirsty, and the concern is that as it spreads, it uses more of that valuable water.”

Tamarisk is now making a forceful entrance into the Animas River valley, joining Russian olive and Siberian elm, two invasive trees that have been on the local landscape for many years. The tree has long been a fact of life on the Colorado and San Juan rivers but is a relative newcomer to the higher, local watershed. Wegner noted that changes in climate have opened the door to the tree.

“Historically, tamarisk has been a really bad problem at lower elevations along the Colorado River,” he said. “But it’s migrating up the rivers. As climate changes with the continued drought, tamarisk is moving into places it traditionally hasn’t been seen.”

Tamarisk is also moving into the local watershed from local yards and gardens. Many Durango homes have ornamental tamarisk on site, and those pet trees contain millions of seeds that blow into and flourish in the wet flood plains of rivers.

“The problem is a lot of tamarisk has been planted in Durango, and it’s getting ready to bloom right now,” Wegner said. “Each tree has millions of tiny seeds and all it takes is a little wind to spread them.”

Barry Rhea, of Rhea Environmental Consulting, has spearheaded efforts to turn back the Russian olive invasion in recent years. He advocated tackling the tamarisk problem as soon as is possible. “Tamarisk is still not as prevalent as Russian olive in the Animas River valley,” he said. “But with any noxious weed, once you recognize you have a problem, it’s good to get on it as soon as possible.”

Controlling the spread of tamarisk is a daunting task. It can be accomplished mechanically by cutting down and poisoning trees or biologically with the introduction of a leaf beetle that feeds only on tamarisk. However, any effort must go beyond killing trees, according to Carlson. Native habitat must also be restored after the tamarisk is gone.

“The objective is not just to kill them, but to also restore native vegetation,” he said. “The rivers of Colorado have been very hard hit by this tree.”

Rhea also argued that any effort needs to go beyond tamarisk and target all invasives. “If anyone is contemplating an exotic shrub campaign, it should not exclude any species and should include tamarisk, Russian olive as well as other weeds,” he said.

Several local groups, including the Friends of the Animas River, are taking up the challenge. Wegner noted that FOAR’s existing Russian olive effort is being augmented to include tamarisk, saying, “Friends of the Animas River is currently expanding our Russian Olive Initiative to include a Tamarisk Removal Initiative.”

A coordinated, basin-wide approach is also in the works. On Tues., May 2, nearly a dozen groups and agencies met at the San Juan Public Lands Center with tamarisk control at the top of the agenda. When the day concluded, the Greater San Juan Basin Watershed Group had formed with the goal of eradicating tamarisk from the entire San Juan River Basin. The Tamarisk Coalition’s Carlson noted that the new group might be on to something. “It’s a serious problem, and it needs to be addressed,” he said. “The best way to do that is involving as many groups and stakeholders as possible and addressing the entire watershed.”

Looking to the coming weeks when the trees go to seed, Wegner argued that local residents need to consider themselves part of the process. “We can do our best to tackle it in the river corridor, but just two blocks from my office there’s a stand of tamarisk in someone’s yard,” he said. “That’s about to go to seed, and we all know where the seeds are going. Education might just be the most important step in this.”

For more information on local tamarisk remediation, contact the Friends of the Animas River at 259-2510.

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel