Exhibit sparks debate on cultural appropriation

| | “Honoring the Nez Perce,” by Judy Hayes, is now on display at the Durango Arts Center. The painting is dominated by Native American text and themes and has sparked a local dialogue on whether intermingling of cultures is appropriate in art./Photo by Todd Newcomer. |

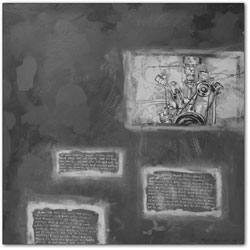

| | Tirzah Camacho’s painting, “Waiting,” hangs on display at the Durango Arts Center as part of the “Earth, Stories, Marks and Memories” show./Photo by Todd Newcomer. |

by Jules Masterjohn We live in a world flavored by an intermingling of cultural traditions. It wasn’t but a mere 125 years ago that cultural exchange, affected by train travel and photography, gave rise to the modern era and changed Western art forever. In early 20th century Europe, the world art center at the time, many images and artifacts from non-European cultures were becoming available to European artistic and intellectual communities. One often-cited example is Pablo Picasso’s painting, “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” in which the artist painted an African mask as the face of one of the French sex workers in his famous group portrait. It is well documented that Picasso’s fascination with African art influenced his aesthetics and nurtured the development of his unique, multi-perspective paintings.

Some say that the artist was “inspired” by the geometric forms of the Dogon ceremonial mask, that its incorporation into his painting reflected an admiration of their aesthetic simplicity. Others claim that Picasso “stole” the image from the African culture. Within this latter perspective, the acquisition by a dominant culture of a minority culture’s heritage – their religion, ceremonies and sacred symbols – can be considered an act of “colonization.” Each of these perspectives describes the slippery, sloping territory of what is called “acculturation” or “cultural appropriation.”

The topic of cultural appropriation is diverse, complex, sensitive and hotly discussed. The debate becomes a wildfire when there is economic gain tied to the appropriation of cultural imagery. Charges of “theft” or culture stealing are lodged, and responses citing oversensitivity are hurled in return.

Last Friday night during the Spring Gallery Walk, some visitors to the Durango Art Center’s exhibit, “Earth, Stories, Marks, and Memories,” stumbled into the rabbit hole of cultural appropriation.

The first to slip into the abyss was one of the exhibiting artists, Tirzah Camacho.

Actually, Camacho grabbed my hand and we slid in together.

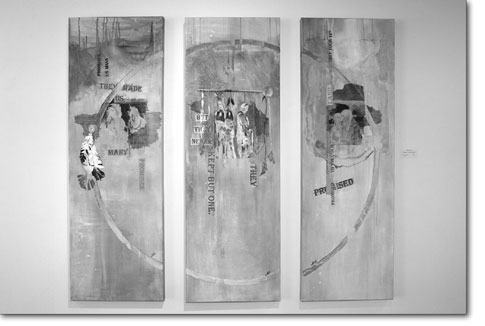

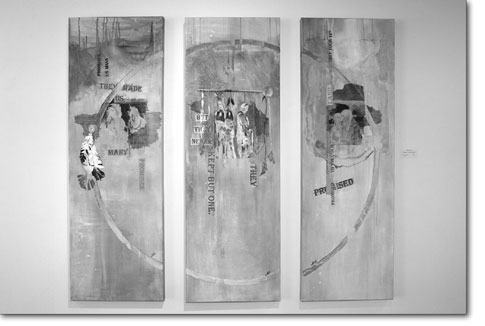

Camacho was standing in front of a large painted triptych, “Homage to the Nez Perce,” its bold imagery and powerful text stating: “They made us many promises but they never kept but one. They promised to take our land … and they took it.” As a Laguna Pueblo, she sometimes 4 uses text in her work but never makes blatant references to her heritage. As I commented on her new subject matter, she was obviously affected. “It’s not my painting,” she replied. I felt embarrassed: The painting’s statement is written in a first-person voice, so I assumed that the painting was created by Camacho, the only Native American displaying paintings in the exhibit.

The rabbit hole grew darker. She told me, “Only Indian people get to use these symbols … it is our birthright as Natives. We have so little left, and even that is being taken from us.” Though she has strong feelings that support her statement, as a contemporary artist, Camacho steers away from stereotypic Indian images – feather, arrows, dancers, etc. She continued, “I feel like that subject matter is dated and there is a fresh approach to be taken. In my paintings and prints, religious icons surface at times but I don’t want them to dominate. When I use Indian symbols, they are undertones that could be understood by someone who is knowledgeable in these things. My fear is that people will expect me to ‘play the Indian card.’ That has happened numerous times tonight.”

A few minutes later, all the artists spoke to the gallery visitors. Judy Hayes, the maker of the Nez Perce painting, told us that she felt that she was Native American in a past life and that her images come to her in dreams. For Hayes, her “Native American” series is heart-felt and offers a poignant message. In the painting “Honoring the Nez Perce,” she makes this clear by using the words of Chief Joseph across her canvas, though no quotation marks or attribution to the elder is apparent. Many people that I talked with at the exhibit mistakenly assumed that those words belonged to the artist. This mattered to some and was irrelevant to others.

Many agreed that Hayes’ painting shows well-developed technical skills through its dynamic composition, contrasting color, illusion of depth and surface texture. Some viewers look to more than the aesthetics of visual elements to find merit in an artwork. Kelly Rogers offered, “If you have the talent and ability to pull the viewer in with the character of the work, which clearly this artist does, you have the responsibility to be clear about the message.”

Artist and graphic designer Mike McPherson added, “A culturally sensitive Caucasian person should not, absolutely not, co-opt sacred elements and designs from Native cultures.”

In contrast, artist Victoria Coe believes, “No one ethnic group owns anything. What matters is what you identify with.”

Artist Alison Goss also appreciated the technical aspects of Hayes painting. When asked about the subject matter, Goss replied, “I have tried to develop my own imagery to show what is authentically mine.”

Goss’ comment echoes the sentiment from Camacho: that being an artist is about creating from one’s personal experiences. Camacho offered, “As a contemporary artist, what interests me is creative commentary about life. What would interest me is to tell me why you think you were an Indian in another life, explain that to me through words and images, not just capitalizing on my culture’s pain. My pain is from this life, not from a past life.”

Jackson Clark, of Toh-Atin Gallery, who specializes in selling Native American and Western art, sheds a different light. “The ethnicity of the originators of any of these ancient symbols is unclear. Maybe a Celtic person carved a Kokopelli figure on a rock and some Athabascan-speaking person saw it, began using it widely, and it became attributed to Native American cultures. A perfect example of this is the swastika. A lot of people see it as a Nazi symbol, yet it goes back to the Greeks and the Byzantines. So, if I use a swastika, who am I stealing from?”

Whatever the “truth” is about who owns what culturally, the debate will likely continue. We are often unaware of how powerfully we impact each other, personally and culturally. No doubt, there will come a time when the differences among us are evened, offenses are righted and wounds are healed. Until then, nurturing our understanding, respect and compassion for another’s experience seems to be the order of the day. n The exhibit “Earth, Stories, Marks and Memories,” is on display at the Durango Arts Center through May 23. Gallery hours are Tuesday – Saturday, 10 a.m. –5 p.m.

|