| ||

Girthing your shallots

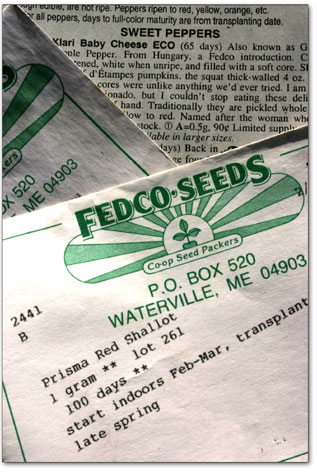

by Chef Boy Ari Winter pow-pow, summer nudity, autumn reflections, spring’s promise … we all have our reasons for liking our seasons. Me? Well, with a gastrointestinal tract that doubles as my central nervous system, I rate the seasons by their flavor. Summer for fresh stir-fry, salad and berry pie. Autumn is for all-out feasting and stocking up for winter, which is for chewing fat, forgetting about summer and, believe it or not, starting seeds ahead of spring. I used to want to grow my own food and live off the land. But I’m coming to grips with the fact that I am not a homesteader, and that’s OK. Living in community is a beautiful thing in many different ways, if done right, and the world isn’t big enough for us all to have our own back 40. I still raise a big garden, but I’ve adapted my plantings away from self-sufficiency, with an eye toward ensuring myself the things that my community doesn’t usually provide, such as a tomato picked five minutes ago, instant parsley or certain crop varieties that farmers around here don’t usually sell, like Klari Baby Cheese sweet peppers, borage flowers and asparagus. Crops like squash, potatoes, beets and corn I leave entirely to the farmers, and when they’re in season I acquire them, either on the open market or via private negotiation. I acquire enough to get me through the year. There are also crops that I grow a modest amount of, like kale or peppers, so I can always run to the garden and grab some for any meal, but I also buy the same things in bulk at the end of the summer to freeze or pickle, respectively, and eat on all winter. Doing business with the growers in my neighborhood does wonders for my social life, since farmers are among my favorite people. I get to meet them and give them money, which makes them like me. I also acquire recipes, observations great and small, and really good, tasteless jokes, at no extra charge. When you take into your body the food that someone has cared for, a bond grows. There are, however, a few items that I do grow in vast, perhaps absurd quantities, despite the fact that many fine local farmers grow them, too. Raising these crops – all of them, interestingly, members of the lily family – is a little piece of my old homestead fantasy, giving me the year-round belly rub with the land that I still yearn for. I never buy garlic. Ever! Except in highly unusual circumstances, or when I’m far from home. When I’m in my kitchen, if I need garlic I go to the garage where it hangs, grab what I need, and it makes me very happy. With shallots at six bucks a pound, growing them is partly an economic decision. I grow sweet onions for eating raw and occasionally cooking, but I prefer to cook with shallots. Having leeks standing in the garden from August into winter gives me the option of adding their buttery sweetness to the meal at hand, as well as the possibility of meals that include all my lilies. If you want to be like me, you’re out of luck unless you planted your garlic last fall. If you did, there’s a good chance it’s already poking through the earth, visible under the thick layer of mulch you hopefully spread. If the mulch is really thick, you might need to pull it away from the plants to help them find the sun. Don’t let garden stores convince you to plant your shallots as bulbs. Bulbs are more expensive than seeds for what they yield, and no less work. So plant shallots from seed, with the leeks and the onions, and do it soon. The sooner you start these lilies, the bigger they will grow – and with these guys, bigger is better. The seeds’ first needs are water, warmth and spongy, well-aerated dirt. If you’re hardcore, you can mix your own potting soil out of peat moss, perlite, compost and other goodies. Or you can buy potting soil premixed. Sprinkle the seeds on an open tray of watered potting soil, as evenly spaced as possible – about a centimeter apart – then sprinkle a little more soil on top, and water again. Don’t let the soil dry out, but don’t over-water it, either, and keep the seeds in a warm place – I have mine on heat pads in the basement furnace room. Once they sprout, keep them by the window, in a heated greenhouse, or under grow lights. Every time they get to be about 6 inches tall, grab a pair of scissors and trim them down to about 3 inches, across the tray. This will increase the plant’s girth, and that’s what we want. With these lilies, height means nothing when it comes to bulb size. Girth is everything. Transplant your lilies in late April, about 6 inches apart, with a nice layer of straw mulch in between the plants. By mid-summer, you can start pulling your lilies, though they will keep growing well into fall. If I get my way, I’ll be pulling my lilies ’til I’m pushing up daisies. •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel