| ||||

One of the oldest professions

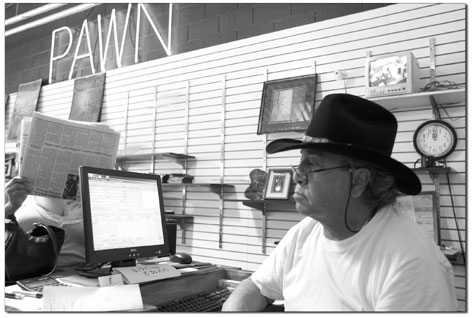

by Jeff Mannix It’s about the money, period. No cute little sticky notes; no nifty key rings or ballpoint pens; no warm-and-fuzzy bears for the kids; no dog bones. It’s all about money in pawn shops: They have it and will lend it in proportion to the value of just about anything you bring to secure repayment. This is banking distilled to its basic elements. There are no credit checks, application forms, waiting periods, insurance requirements. Pawn shops have no cushy waiting areas with coffee and cookies, no pretty attendants or estate planners, no grandiose buildings or lobbies filled with priceless collectables and hundreds-of-thousands-of-dollars worth of furnishings and decor. They’re in strip malls, next to bus stations and liquor stores or converted gas stations. You walk up to a shabby counter with your stash and somebody in jeans and a baseball cap examines your goods and declares its pawn value – take it or leave it. “It’s probably older than language,” says Bruce Dominey, the enthusiastic owner of Rocky Mountain Pawn and Gun at the corner of 32nd Street and East Animas Road. “You want to borrow a spear to hunt lion, you leave three goats and two women until you bring spear back – and I keep the best looking goat or woman in exchange,” chuckles Dominey with the confidence of an old-time sideshow barker. Pawnbroking dates back 3,000 years to China, is mentioned in the Bible, and kept the Middle Ages afloat in defiance of the usury laws of the church. The House of Lombard in England and the Medici family of Italy operated chains of pawnshops in Europe beginning in the 14th century, and Queen Isabella pawned the crown jewels of Spain to finance Columbus’ journeys to the New World. Today, pawnshops can be found in just about every city and hamlet throughout the world, and there are a number of chain pawnshops in the U.S. – Super Pawn, Cash America, EZPawn, Big State – with as many as 1,500 locations. In Durango, we have three locally-owned pawnshops, all offering banking services to the antiestablishment and a virtual candy store to garage-sale minded shoppers. Here’s how it works. Let’s say you’re a “Fort Leisure” college student who owns a souped-up mountain bike that costs $2,500 new. It’s winter, bike riding is out and skiing is in. You need new skis, but you don’t have the cash. You take your mountain bike down to a pawnshop to finance your snow habit. The pawnbroker is an encyclopedia of value, has a bookshelf of reference books for the more obscure items, and became a genuine genius of value with the success of eBay. The used value of your bicycle is now $800 (nearly half the value is left in the retail store where you bought it), so the pawnbroker will give you half its used value: $400. Your loan contract is for 30 days, and you will be expected to pay between 10 and 20 percent per month in interest, depending on the shop and the amount of the loan. You can extend the life of the loan by paying the interest each month, so to store your bike for the winter

and finance a new snowboard, each month you’ll pony up $40. Come April or May you will have paid $200 in interest, and now that the weather has driven you off the snow and it’s time again to pedal the peaks, $400 will get your bike back. It’s tough love, but try going to a bank to borrow $400 for a snowboard at 9 a.m. and be on the slopes by noon. “We take no risk,” says Cole Hyson of Colorado Trading Company on E. 8th Avenue. “We don’t want to own anything; we just want the interest.” Yet pawn shops are full of merchandise that was never redeemed, in effect sold to the pawnbroker at fifty cents on the dollar and retailed at 50 to 60 percent of its cost new. These guys didn’t just fall off a turnip truck; they make money when the goods come in, then make money when the goods go back out if loans aren’t repaid. Everybody wins . . . but the pawnbroker wins a little bigger, not unlike a bank. For Orlando Martinez, manager of College Corner Pawn at 810 East College Dr., pawn is a form of helping people in need. “It’s not so much about what something is worth,” Orlando says in a gentle, patient way. “We usually are told just how much money a customer needs to meet an unexpected bill when he brings in his collateral. We have a lot of repeat customers who just need to get to next week’s paycheck. They’ll bring in a power tool or a rifle that we could lend $200 on, but he needs only $100 to pay his electric bill. We help this customer, and we know he’s coming back to get his stuff.” Orlando and the other pawnbrokers say that their business is 85 percent repeat. Preconception is the limiting factor for pawnshops, according to Dominey at Rocky Mountain Pawn and Gun. “People see pawn shops on TV and in movies, where stolen goods get fenced by junkies and punks,” he says. “Well, we can’t pawn a thing without seeing a photo ID and filling out a form that the police pick up every Friday. Nothing stolen comes through a pawn shop; we’re licensed and inspected more than Bank of America.” But even though pawnbrokers are proud of the service they provide and delighted with the rate of return they get, none are too far away from a loaded gun under the counter and all have eyes in the backs of their heads and practical Ph.D.s in applied psychology. A pawnshop is a seductive place with an air of danger and the tingle of chance. Yet there is something very real about this ancient marketplace, something vital, something honest and pure as dirt. “It’s the oldest profession in the world,” says Dominey. “You might have had to go borrow a few bucks to go see the second oldest profession.” •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel