| ||||||

The power of the ring

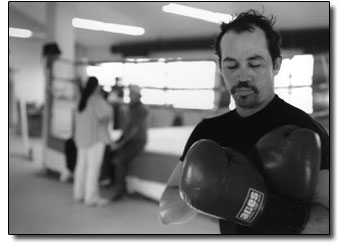

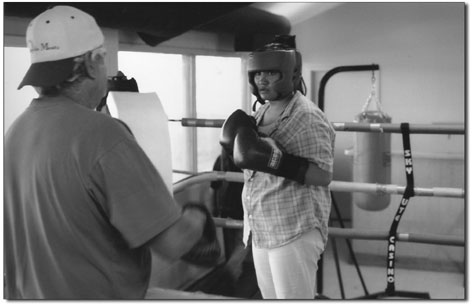

by Shawna Bethell "C’mon! Put the pads on,” Katrina Martinez, 15, taunts Ernie Trujillo. Waving gloved fists, the girl draws Trujillo, her sparring coach, into the ring. With makeup, long black hair and a shy smile, her outside ring persona is incongruous with her in-ring punch. Martinez is one of 18 on the roster at George’s Independent Boxing Club, an Ignacio, club that has churned out several champions over the years. Turning his cap backward and putting on pads resembling catcher’s mitts, Trujillo climbs casually into the ring. “Boom, boom, boom,” he says as her punches hit a rhythm on the pads. Looking on is owner George Manzanares, who opened his first boxing club in 1969. “I will take her to champion,” Manzanares says later of Martinez. He looks fondly at her, the way he looks at all his kids – part coach, part mentor, part father. “If I don’t get too old first,” he laughs. At 72, Manzanares still climbs into the ring with his boxers, from the beginners to the pros. “It keeps me young,” he says. Manzanares started boxing at 8, back during World War II, at a club started by Durango’s Chuck Hildebrandt. By the time Manzanares went to Korea with the military, he’d become a good fighter and was be pulled off the front lines to train in Satoshi, Japan. He then boxed for the military, his dream of becoming a world champion ended by a combat injury. With his eyesight diminished and injuries to his left arm and leg, he decided instead to coach, taking others to the professional level. Successful in his career change, national and international champions have come up through the ranks of George’s Independent Boxing Club. “I can see a boxer real quick,” he says. “It’s his demeanor, the way he holds himself. A lot of guys come in, and they don’t have the look in their eyes, but some are naturals. Some become boxers.” Back in the gym, Evergito Martin Barcia’s red shoes brush the surface of the padded ring as he moves around the square lightly and quickly, throwing and dodging punches. He is small and wiry, focused and intense. Barcia, a.k.a. “The Nicaraguan Nightmare,” plans to go pro. “I had a vision,” he says. “I saw snowy mountains in my dreams, and my hands in front of me, like I was boxing.” He holds up bare fists in a fighter’s stance. His green eyes are youthful in his excitement. A carpenter living in Durango, Barcia had heard of Manzanares, so he drove to Ignacio and started asking around. He finally found his soon-to-be coach in the grocery store. At age 34, Barcia is pushing the age barrier to go pro, but he is determined and feels he is still fit enough to push his body to the limit. He boxed as an amateur in the Nicaraguan military before coming to the States. Now, he feels, is his time. His first pro-level fight is scheduled for the end of this month. The irony of this seemingly violent sport is that it has been a saving grace for many kids who have come to Manzanares, whose ultimate goal is to help kids who may be headed down the wrong path. “My desire is to have this gym packed with every little kid who’s in trouble,” he says. “So many kids get caught up in drugs and alcohol, or maybe their home life is bad, this is a way to get them off the streets.”

His efforts have been recognized by his community. In 2000, Manzanares was nominated for and received the Points of Light Foundation Award for his volunteer work with kids. “I believe there is something good in everyone,” he explains, looking across the gym, but also remembering the many lives he’s encountered over the years. “There is a human aspect to everything you do. When I was working in law enforcement, I dealt with people of all kinds, but I always treated them with respect.” He pauses. “I don’t care if someone is absolutely the worst person in the world, there has got to be something good in them somewhere.” Katrina Martinez is one of those kids who found help. “It helps me have confidence,” she says of boxing. “It helps me get out my emotions.” She also feels that after a year working with Manzanares, she has learned self control and how to think before she acts. But in the end, she gives that shy smile and says, “It’s just fun.” In her other world, the one outside the ring, the 15-year-old is Southern Ute Royalty and travels to pow-wows representing the tribe and the state of Colorado. She also participates in traditional dancing. “It’s funny. Everybody wants to know what it’s like being a boxer. They want to know if it hurts to get hit.” But Martinez walks the line between the “girly girl” and the “boyish girl” well, and sometimes uses it to her advantage. “When I go to weigh-in for a match, I do my hair and makeup and the other girls think I’ll be easy to fight … but then they figure it out in the ring.” Her coach shakes his head at the girl. “No,” Manzanares confirms. “The other girls in our club won’t even spar her.” Micco Wesley, a Muskoke tribal member from Tulsa, Okla., began boxing two years ago while attending Pueblo Community College, but at the time could not be fully dedicated to the sport. “It’s all about perspective,” says Wesley. “People think boxing is violent; they think we are getting hurt. But our bodies are ready for it. It’s why we train so hard.” Wesley further explains that in the ring a boxer should remain relaxed so the body can better absorb the punch. He says it is a mental sport, knowing how to pace one’s self, understanding the opponent. He likens training to attending school. If you sit out for a while, you get out of the rhythm of training like you get out of the habit of studying. But since February, he has had the time to focus on his potential boxing career. Now it becomes second nature, the rhythm of the bag, which he makes appear effortless, and the instincts of the sport. Leaning against the back wall of the gym, watching the boxers being instructed by Manzanares, Trujillo echoes the sentiments of the younger man. “If you don’t make this ring your world,” he says. “You’ll never be a champion.” •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel