|

| ||

| My summer vacation: from the silly to sublime

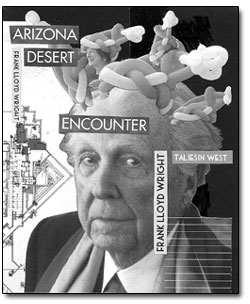

by Jules Masterjohn Summer can be a time for engaging in activities that are lightweight … like taking a vacation and washing the car. A few weeks back, I stopped to get my dusty transport vehicle hosed off at a local automated car wash. Not intending to have an art experience, I was tickled to find that a “Tri-color Wash” was offered. As one who leans toward the aesthetic, even if it doesn’t make fiscal sense, I chose the colored detergent wash and slipped my crisp 10 spot into the vending machine. As the weakly-hued pink, green and whitish foam made a lattice pattern across my windshield, I chuckled out loud with the realization that I had expected something, perhaps transcendent, from this new art encounter. Here the elements of line, color and pattern, borrowed from 35,000 years of art-making, were used in the service of attracting buyers like me. Throughout history, these same visual elements have been used to create works of incredible inspiration and meaning: here the commercial world had delivered a puny aesthetic event. Frankly, I was unimpressed. As the high-powered sprayers made their passes around my car, I reminisced on a riotous utilization of color and shape made into the form of balloon hats worn by guests at a recent party. In this case, the same inspiration that put colored foam detergent in a car wash – to infuse our world with a bit of artistic flair – was raucously successful. Imagine local writer Judith Reynolds wearing a blue, grey and black balloon chapeau twisted into a seriously silly headdress, resting on the source of her considerable intellectual abilities! In the hands of balloon artist and Catch-It-Quick juggler Michael Taylor, simple, air-filled latex tubes became psychic extensions of each wearer and a delightful representation of a fun interaction between art and consumer culture. Out of the car wash and back on the road, I made a U-turn in my mind and created a mental list of ways in which art and commerce interact. The first example that sprang to mind was the art of Andy Warhol. His silk-screened images of Campbell’s soup cans and Coca-Cola bottles, as well as the images of Marilyn Monroe, represent Warhol’s commentary on mass culture and its concerns: selling products and icons. Warhol took these pedestrian goods used in daily life and “elevated” them by introducing them into the fine art realm. Frank Lloyd Wright, on the other hand, took art concepts and integrated them into his designs for daily living. Wright’s innovative use of materials and new concepts of utilizing space within domestic and public buildings have profoundly affected how today’s living environments look, feel and function. Earlier this summer on a trip to Scottsdale, Ariz., I toured Taliesin West, unarguably Wright’s most ambitious project. Serving as the Wright family’s winter residence for more than 20 years, and the current location of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Taliesin West is perhaps one of the world’s most profound modern architectural works. Even though I have seen photographs of its architectural novelty and know of Wright’s influence as America’s pre-eminent architect, I was unprepared for the quiet, sublime beauty of the place. Wright’s intention, as he put it, was to “build ourselves into the life of the desert according to the life and character of the great desert itself.” He accomplished this by “capturing” the landscape inside of the building using what he called his “desert masonry,” rock and concrete walls that feel as if the desert itself had made them. The name “Taliesin,” meaning “shining brow,” well describes Wright’s placement of ample windows within open interior spaces, offering vistas of the surrounding valley. Situated on a rocky rise, the views from Taliesin West allow us to understand our place within the context of the vast and rugged landscape. While on the tour, I came to understand how significantly Wright’s vision and experiments in the Arizona desert influence our everyday lives. According to the docent who guided our group through the extensive building complex, Wright was the first architect to explore and implement recessed lighting, both in ceilings and floors, as well as to design the first aisle or pathway lighting. He also pioneered the use of glass as the primary material in doors as well as created corner windows. Perhaps the most far-reaching design concept created by Wright was the open floor plan, a layout with a large living area common to many homes built today. A strict believer in “form following function,” Wright’s purpose in designing a large living area was to encourage individuals to gather together, to create a space for community exchange. While sitting in the large open living room of Taliesin West, with its 5-foot high raw rock and concrete walls, and translucent ceiling panels that allow daylight to softly filter in, I could almost hear the excited conversations among the apprentices that would have gathered there in 1940, to celebrate the completion of the building of Taliesin West. Not only was Taliesin West the chosen location for Wright’s seasonal home, a place for him and his family to escape the severity of Wisconsin winters, it also served as the school and residence for the apprentices who helped in the building process. Sometimes up to 30 individuals would be at the “desert camp” at once, studying, working and living together. In 1938, when Wright and his family and dozens of apprentices settled into their canvas tent encampment to begin their first winter of building Taliesin West, Wright was 70 years old. Responding to the creative energy innate in him, Wright followed a vision, a desire, and deep commitment to learn from the desert environment. Later, Wright wrote in his autobiography, “Our Arizona camp is something one can’t describe, just doesn’t care to talk about. Something in respect to excellence … .” Taliesin West is one of 49 of Wright’s public and private buildings that can be toured. • Go to www.franklloydwright.org or call (480) 860-8810 for tour information.

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel