|

| ||

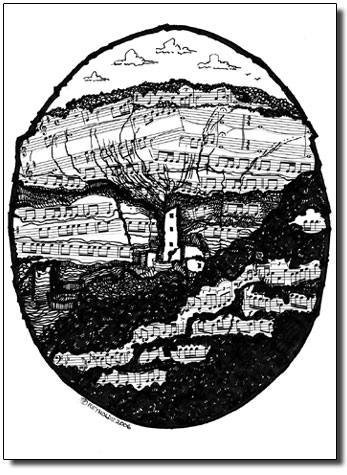

| Breathless in Colorado

by Judith Reynolds Gasping for air, Steven Weger barely makes it through his opening trumpet solo. “I’ll be better tomorrow,” he stammers, “when I’ve adjusted to this altitude.” Co-principal trumpet of the Fort Worth, Texas, Symphony, Weger is in town briefly for a rehearsal of Steven Procter’s new piece, “Mesa Verde Suite.” Commissioned by Music in the Mountains and funded by local philanthropist Betty Haskell, the work has a three-part “world premiere” schedule. The first performance has already taken place (June 29) at the official Mesa Verde centennial celebration. The second will be Sun., July 16, at an upscale dinner/concert at the park’s Spruce Canyon Overlook, formerly known as the Spruce Canyon Parking Lot. (American marketing at work).The third performance will be at the Durango Mountain Resort on July 22, a regular Music in the Mountains concert. But rehearsals come first, as Weger and his colleagues in the Festival Brass Quintet have learned. All five have a love-hate relationship with our thin air. Trumpeters Weger and Stephen Dunn, trombonist Byron Herrington, hornist and composer Procter, and tuba player Stephen Ross have had to adjust to our altitude before. Preparing for Procter’s new piece, the musicians jokingly complain about all the pesky eighth-note rests. For the work’s long, lyrical phrases, brass players need time to take deep breaths. Short rests don’t cut it. After several tries to sustain phrases in one breath, the players gasp, groan and complain again to Procter. “I wrote this at sea level,” he jokes back. “It seemed like a good idea at the time.” *** The 18-minute work has eight movements, seven more than first envisioned. “The original intention was to write a one-movement work – about eight to10 minutes long,” Procter said during rehearsal break. “At the beginning I didn’t have a story line, but I had a lot of separate ideas. Then I simply got stuck.” To work his way out of composer’s block, Procter said he did what he always does: research. “I started reading, and my wife and I decided to take a tour of sacred sights in the Southwest, Chaco, Mesa Verde and others. In Chaco, we met a great guide – brilliant – and his name also happened to be Sterling. He brought the place alive. He talked about the beginnings, why people may have come, why they stayed, and why they may have left.” He wasn’t necessarily looking for a story line, Procter said, but there it was along with the “discovery” by the Wetherills and an epilogue that looks to the future. “Eventually, the pieces started to come together, and I ended up with an eight-movement work.” A prologue, “Anasazi Vision,” opens the work. Scored for one, then two Native-American flutes, it will be performed by David Nighteagle-Lakota and Procter himself. Both improvise on Procter’s motifs, creating a sense of mystery before the flutes merge with the quintet for Part II. The rather dark “Arrival of the Ancients” evokes a tribal procession, Procter said. The third through fifth sections center on the beauty of Mesa Verde. “First Light” rolls in on waves of ascending lines followed by Michael Haffeman’s steady drum pulse. “I imagined the first light of the first day,” Procter said. “The people must have settled in and looked over the canyon. What was it like to be in this place at first light? It had to be an important moment, and I wanted the music to reflect that.” “Anthem,” Part IV, is a “purely musical expression of a grand and beautiful place,” Procter said. And it is here that the composer expands on a musical form he is known for: arrangements of hymn tunes for brass quintet. Part V is titled: “Song to the Earth,” and leads directly into “Kiva Vision/Departure.” “This section reflects a presumption of mine,” Procter said, “elders gathering to discuss whether to say or to leave. They must have had a vision.” The dark mood of Part VI shifts dramatically in section VII, “Wetherill Discovery.” Rhythmically reminiscent of Ferde Grofé’s “Grand Canyon Suite,” it has the jaunty air of young horseback riders. “I have a little fanfare that announces their coming over the edge of a canyon and seeing the remains of a city. It’s meant to have a sense of discovery.” In the Epilogue, motifs from earlier sections can be heard over the pulse of the drum, driving forward with an air of confidence. “Once I assembled the ideas, all the pieces fit together,” Procter said. “The whole piece got bigger. It was like starting out to write a magazine article and ending up with a book.” “Mesa Verde Suite” will be part of Music in the Mountain’s “Southwest Heritage” concert July 22. The concert opens with Copland’s “El Salon Mexico” and continues with Michael Mauldin’s beautiful “Promontory Night” and Procter’s suite. Mozart’s “Piano Concerto No. 23 in A” follows, with pianist Andrius Zlabys. And the concert concludes with Dvorak’s “Slavonic Dance No. 7.” By then all the festival musicians, brass included, will have acclimated to Colorado’s altitude. “It’s amazing how much difference it makes,” trombonist Herrington said at the early rehearsal. “Altitude affects all our responses. Everything’s different – breathing, phrasing – even our lips.” Seems even world premieres are made of such mundane things as breathing, parking lots and lips that work. •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel