|

| ||

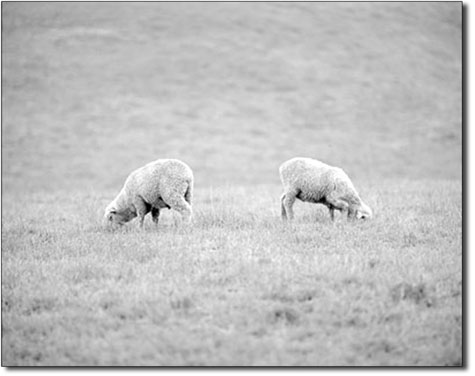

| 50,000 sheep can't be wrong

by Chef Boy Ari We didn’t climb to the top of the food chain to eat vegetables,” explained Dan Ryan, who sells lamb at Missoula’s Clark Fork River Farmers’ Market on Saturday mornings. In front of his cedar-clad refrigerated trailer, Dan elucidated the subtle side of sheep farming: “We’re waiting for them to get big so we can slaughter them,” he said. The lambs in question comprise his spring herd, replacing his sold-out fall lambs, born last December. In nature, mating in summer and giving birth in autumn is a no-no; the lambs would die. But fall lambing is common on the farm. They eat grain and milk from their grain-fed mamas all winter, but no fresh grass. Spring lambs, on the other hand, eat the young tender shoots of springtime. Whoever you buy it from, it’s more likely to be free range and, well, more natural. The distinction between lamb and mutton lies in the flavor in the old versus young meat. Officially, 14 months is the lamb-to-mutton cutoff – a line drawn on consensus based on the flavor at that age; biologically, a lamb reaches sexual maturity at 6 months. Many people actually prefer mutton to lamb. Both have essentially the same flavor, but with mutton there’s more of it. Still, it’s a good idea to trim the flavor-packed fat off of mutton, unless you’re a true glutton for mutton flavor. The sight of Dan’s sheep grazing on a hillside north of town, visible to all from the highway, helps make him a poster child of sorts for the Clark Fork Market, also known as the “Meat Market.” One of the market’s goals is to provide local meat producers the opportunity to market directly to customers. “It’s not just about cutting out the middleman,” Dan explained. “It’s about making people aware of the agriculture going on in their neighborhoods and keeping the dollars local. Last year I paid $8,000 to my processor, Lolo Locker, and that money stays here. I could just load my lamb on a semi and send it away. That’s less work for me, but then everything’s gone. And,” he adds, “it’s fun to come to market and sell the lamb myself.” A customer entered Dan’s trailer, gushing about the lamb shank sambuca she likes to make. “We suck the marrow out of those bones,” she said, “and we feel like we’re living.” Lamb shank sambuca is a wee bit too fancy for the man at the top of the food chain. “I don’t really care what they do with it,” he shrugged. “I’m not really into The Joy of Cooking.” But despite Dan’s rough and redneck persona, there’s a soft, almost tie-dyed side to the lamb guy. His business, I discovered to my surprise, is officially registered as Montana Sprout Farm. “We used to grow and sell 2,000 pounds of sprouts a week,” he admits, quickly adding, “Just because you grow it doesn’t mean you have to eat it.” He tossed me a packet of lamb ribs. “Here’s a cut of meat that nobody seems to want,” he said. “But I think they’re great. Parboil them for five minutes to get the fat out, then throw them on the grill.” I went home and boiled half the rack for 10 minutes. When I put the ribs on the grill, I saw no shortage of fat on them. I let them sizzle and sputter ’til the outside was a crisp brown, seasoned them with salt and pepper and dove in. If the expression “chewing the fat” has any grounding in a literal act, this could be it. My teeth made little headway. My face got covered in grease. But my mouth couldn’t stop eating. The ribs tasted too damn good. The next day, intrigued by the challenge of unlocking that flavor without sending my jaws to rehab, or my arteries to Roto-Rooter, I browned the other half-rack of ribs in a cast-iron pan. Then I put the pan in the oven at 350 degrees, where the ribs continued to brown. Once in a while, I’d turn the shrinking ribs in the rising lake of grease at the bottom of the pan. After a few hours, I poured off the grease, which totaled more than half a cup. Cooked to a crisp but not burned, all the fat and toughness was surely gone. Now I had to replace the juices I’d just cooked off. I added white wine, a little cider vinegar and apple cider. I tossed in four cloves, three bay leaves and a teaspoon of cumin. I cooked it another hour with the lid on, checking it often and adding more liquid when necessary. The smell was intoxicating. It tasted like it smelled and shredded like pulled pork. This was the joy of eating at the top of the food chain. •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel