| ||

‘Every show is your last show’

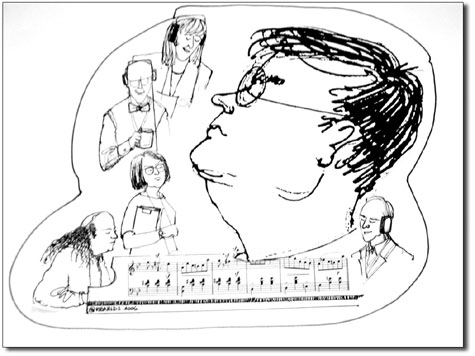

by Judith Reynolds If you’re a fan of Garrison Keillor, chances are you’ve already seen the new movie, “A Prairie Home Companion.” If you’re a fan of film director Robert Altman, ditto. I’m both. Now you know what to expect – a positive review noting, maybe, a flaw or two. How could it be otherwise? If you’re not overwhelmed by Keillor or Altman – well, I don’t know what to tell you. This is a backstage story with a splendid ensemble cast. It is not a documentary about Keillor’s famous radio show but a fictional account of its demise. The cast consists of Prairie regulars, GK himself, Tim Russell, Sue Scott, Tom Keith, The Guy’s All-Star Shoe Band, all the folks we saw June 13, 1998, when Keillor brought his show to Durango. To add star power, he’s added a coterie of big name actors: Meryl Streep, Lily Tomlin, Kevin Kline, Tommy Lee Jones, John C. Reilly, Woody Harrelson and Lindsay Lohan. The Altman-Keillor alchemy is irresistible. Director and writer thrive on large casts of quirky characters. Here a slew of memorable individuals smile, bump, prod, snarl at, and otherwise engage each other as they prepare for the last performance of a 30-year radio show. Keillor efficiently creates tangled histories. Old arguments ignite and old romances rekindle. Tensions rise as cast members bumpily bring the show to a close and say goodbye to the Fitzgerald Theater in which it has flourished. Yes, there’s a villain, a Texas company, represented by the Axeman (Jones), plans to demolish the beloved old jewel box and slab down a parking lot. In Keillor’s universe, everyone is flawed, and the world is a messy place. The film, too, has its problems, as forewarned. A heady concoction, Keillor’s screenplay brims with nostalgia and unfinished business. The plot may be banal and a little tired, “let’s put on a show,” but it works. The addition of an angel of death (Virginia Madsen) may be too coy for some. Wandering silently into the theater, she eyes potential candidates. When she returns in the epilogue, the conceit plays itself out in a loose yet predictable way. The idea that all things pass away is bedrock in Keillor territory; all of his writing contains a gentle melancholy. Altman’s much darker view (“Nashville”) may have been tempered by Keillor’s humanism. I missed Altman’s famously long tracking shot that often begins his films (“The Player”). Instead, he provides a single shot of a radio tower as dusk fades into darkness. Simple credits appear and disappear as voices deliver farm or kitchen reports over some bluesy music. To be generous, it’s an audio equivalent. The purpose is to quickly create a universe and set a tone for the rest of the movie. It, too, works. The opening frame introduces us to Mickey’s Diner in St. Paul, Minn. There, one of Keillor’s characters, Guy Noir (Kevin Kline) ponders the demise of the radio show. When the camera finally enters the theater and sweeps through hallways and dressing rooms, Altman’s cinematic genius shows itself as he illuminates a magical world. Anyone who attended Keillor’s live broadcast here in Durango knows what the real “Prairie” set looks like. Dominated by an American back porch, the stage spills over with signs for various segments, a handsome Wurlitzer organ, space for the band, Keillor’s lectern, and a sound-effects table resplendent with whistles, shoes, tools and a latched door. All of that’s in the film, plus the wings, the stage manager’s cubby and the cluttered dressing rooms below. As brilliant as Meryl Streep is as one of the Johnson sisters (and an old flame of GK himself), she’s joined by all those other luminaries. They play the characters that Tim Russell and Sue Scott create on the weekly radio show. In the film, Russell plays the stage manager to Scott’s make-up artist. Watch for them again in the epilogue, and you’ll know what happened to them after the show closed. Thanks, Garrison, nice touch. •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel