|

| ||

| Cultivating the inner genius SideStory: United/Unidos/T’áálá’í Níídlí

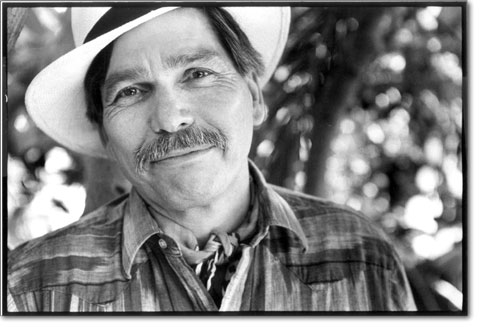

by Amy Maestas A photograph of legendary scientist Albert Einstein hangs on the wall in prize-winning author Victor Villaseñor’s writing space. In it, the stereotypical absent-minded professor, donning his usual drab slacks and Mr. Rogers sweater, pedals a bicycle while grinning widely underneath a dense mustache. To Villaseñor, Einstein embodies the meaning of genius – tapping into unfettered creativity, mental prowess and living a large life. To Villaseñor, everyone is a genius. You just may not know it, he says. “Are you a genius? Do you like to live life like Einstein is on his bike, with wild hair and understand what you do best?” Villaseñor asked last week during a telephone interview from his ranch in Oceanside, Calif. It’s a perpetual question the Mexican-American always asks his audience. Responses, Villaseñor says, are often mixed. Initially, few people admit to such brilliance. But by the end of his lecture, Villaseñor boasts that everyone raises his or her hand. His goal is to help everyone who hears his words of wisdom to see how we all are born with highly creative souls, innate and ripe for nurturing. Unfortunately, Villaseñor explains, the formal education system in America squelches the genius in each student, instead churning out a bunch of robot-like brainiacs who learned only how to memorize and conform. “The thinking today in schools is to just stuff them with information and then test them,” he says. “It does nothing to uncover their natural genius. Educators need to go back to the root meaning of education, which is to lead or draw out the student.” Villaseñor’s words ring especially true against the backdrop of his own life. Born in southern California to Mexican parents, Villaseñor endured a torturous life in the public education system. Teacher after teacher broke his spirit, chastising him constantly for his inability to excel in academics and for always speaking Spanish. The abuse often caused the young Villaseñor to pee in his pants, standing in front of his classmates humiliated by useless mentors hell-bent only on high marks and testing results. Learning was always a struggle for Villaseñor. The lack of compassion from his peers and educators sculpted his anger and resentment toward the education system and the world at large. It wasn’t until he was in his 20s that Villaseñor was actually able to read a book, finally coming to the realization that he had dyslexia – both audio and visual. Essentially, Villaseñor had difficulty seeing and hearing letters and concepts in a linear fashion. When he was in his 40s, he learned that his dyslexia was severe. But it never did deter the adult Villaseñor, who is now the author of seven books. His experiences from years of bucking the system, in addition to coming from a Latino family that has generations of deeply rooted stories and wisdom based on mysticism, indigenous beliefs and gender power, drive his lectures. Villaseñor’s latest book, Burro Genius, is both an unsettling and stirring memoir. From his first day at school, when his teacher degrades him often and openly, to his heated impromptu speech to a group of educators, Villaseñor’s tales stand as tutorials for everything a teacher should not do. During his three-day visit to Durango next week, where he will reach out to adults and students alike, Villaseñor says he will punctuate his personal anecdotes with explanations of “how the brain works and how to get people to get into their feelings.” He believes that people can succeed best only when they are allowed to express themselves from the heart, especially students. “Students’ lights have been turned off,” says Villaseñor, when explaining the failures of the educational system. His message, he says, isn’t about minorities fighting the establishment. Rather, it is helping people become unfrozen in patterns when interacting with each other, moving away from fear as the motivator. Motivating people with fear, says Villaseñor, is manipulative and immature. “When it comes to technology, we are very, very advanced … but emotionally we are still little babies, wondering if we are on the right road. We aren’t. When we finally understand this, we can help students express themselves from their hearts and nurture them.” Burro Genius is a good example, he says, for awakening a revolution not only in public schools, but also in all facets of life. Mostly, he wants people to understand how to stop crushing the students’ cultures and pushing linear thought so roughly that it sets them on too rigid of a course for rousing their geniuses. “Let’s get out of the box and all of us get into our geniuses,” Villaseñor says forcefully. “Because all over the world we are one world and one family.” •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel