|

| ||

| Forging a path of creativity

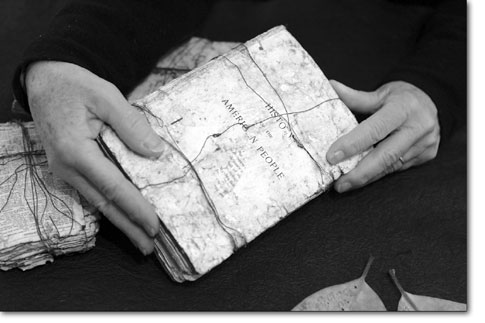

by Jules Masterjohn Until the late 19th century, the world of visual art was populated by objects that were easily identified as “art.” In America during the 1960s, society was confronted by new art ideas that pushed “establishment” boundaries and challenged viewers to broaden their definitions of art. During this time, artists began using the land to create from and within – the environment became the canvas, the studio and the gallery. Environmental art encompassed a movement known as land art or earth art. Some of the earth artists left a big impression on the landscape, like Robert Smithson, who had 6,650 tons of earth and rocks placed in a spiral form into the Great Salt Lake to create his well-known earthwork, “Spiral Jetty.” Michael Heiser gouged 240,000 tons of earth out of a Nevada mesa top, forming a straight line that can be seen from a satellite. Other artists involved themselves in less invasive manipulations of the landscape. British artist Richard Long does not mar the terrain on which he creates. His artistic expressions are “walks” that traverse hundreds of miles through countries all over the world, creating a temporal experience for the artist and a conceptual gem for the viewer. At intervals along these walks, he makes circles of stomped footprints that are erased over a short period of time by blowing winds. His treks are documented with photographs and from these photos, along with maps and journal notes, he creates artworks to share through museums or gallery exhibitions. On his website he states, “Walking enabled me to extend the boundaries of sculpture, which … could now be about place as well as material and form.” Like her mentor and aesthetic kin from Britain, Durango artist Mary Ellen Long (no relation) also comes from the “tread lightly” school of environmental artistry, where the art-making activity does not dominate the land or may not even leave a lasting presence. During the 22 years that Long and her husband, Wendell, lived on 8 acres on south Missionary Ridge, she established an outdoor trail that followed and accentuated the topography of the property’s terrain. The genesis for this path, “Forest Walk,” began as Long hiked the existing trails made by deer and other animals. Her original idea for the trail system was to offer the “walker” a course of contemplation, a pathway to awareness of land and place. As often happens in the creative process, Long’s initial idea expanded into a more elaborate concept that included natural elements like fallen tree limbs, pinecones and rocks, arranged in intentional shapes and patterns along the route. This activity led to the development of a series of “rooms,” or sites, along the pathway in which the arrangement of these indigenous materials signaled a resting spot, a viewing space or a place for reflection. The first “room” created by Long consists of a clearing with a dense grouping of pinecones organized in a circle at its center. Made during a severe drought year, this piece was created as a “prayer for moisture.” Most of Long’s works, whether outdoor site-specific pieces or works created out of doors and brought into the gallery, are subtle documents of and visual responses to the inherent cycles of nature. The grand-scale of “Forest Walk,” wandering through acres of tall trees, is Long’s most developed environmental art piece to date, though she is currently creating a commissioned work for the Edgemont Highlands residential development east of Durango. The Highlands Trail, set by developer Tom Gorton and built by landscapers, will eventually encircle the development. As with “Forest Walk,” this trail winds through the forest passing through various “rooms” containing site-specific works, including a pinecone circle, a “bird perch raft” and other animal shelters like the “Butterfly Shelter.” Seeing these limb and twig structures, it is hard to get a fixed sense that they are a product of human intention for they appear uncontrived. Like beaver dams, these “shelters” look as if they could be the consequence of natural forces and wild animal activity. A particularly intriguing piece occupies a large area where Long has braided clumps of foot-high grasses and laid them on the ground. The delicate, recognizable strands all flow in the same direction, as if flood waters had rushed over them with their gentle force. Other works along the trail are so subtle that they could be overlooked if one was not paying attention. The “Lichen Spiral” stood out only because my eye perceived a repetition of lush green pattern that seemed too regular for the natural environment. In “Circle of Irises,” Long has manicured a once-irregular area of wild irises into a circle, surrounding it with small stones. The round bed sits near the base of a tall tree. Back on Missionary Ridge at “Forest Walk” is the “Burnt Timber Room,” named for the 100-year-old silky, charred snag that dominates the clearing. In this room, many years ago, began Long’s experiments with what has become the artist’s trademark – her “book works,” made by placing layered and bound pieces of hand-made paper upon the forest floor. Her interest was in seeing how the natural elements of weather, animals and insects would affect the stacks and scrolls of paper. Of particular interest to Long are the “worm markings,” continuous and meandering paths etched into the paper by worms and other crawling critters as they traverse the terrain between her pages. For Long, these books “tell the story of what happened at that place.” To me, these volumes are visual metaphors for Long’s own pathfinding as she travels the territory between heaven and earth, following the creative spirit. • Mary Ellen Long’s work can be viewed in the Art Library upstairs in the Durango Arts Center through February. She will be conducting a workshop,” The Book, The Leaf, The Word,” on Feb. 24 & 25. For information call Mary Ellen at 259-4364.

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel