| ||

Awake in the chocolate rainforest by Chef Boy Ari Awake at 4:50 a.m. to the sound of rain crashing on the tin roof. When my alarm goes off 10 minutes later, it’s still raining. In a few minutes, soaked to the bone, I’m trotting down a steep road paved with red mud, slick as black ice. On both sides of the road the jungle is solid green, solid chirps, solid flowers. Everywhere else is solid rain. Moss is thick on the cacao trees, which grow low and wide in the shape of well-pruned apple trees. Orchids and other epiphytes inhabit the upper reaches of the larger trees, like the jack fruit trees, whose extra-large fruits taste like extra-sweet bubble gum and hang down in groups like clusters of watermelon. Clouds cling to the rolling hills of jungle in the distance as I descend to the valley floor. When I reach the main road on the valley bottom the rain has stopped, and I point my feet toward Gandu, 50 kilometers to the north. In Gandu there is a cyber-café, where I will write “Flash in the Pan.” Neither rain nor mud nor a long twisty road will stop the Chef Boy Ari Express from meeting his deadline. It might not be high literature, and it’s certainly not high society, but it’s a weekly dose of high-calorie flavor from some relatively unexplored corners of the culinary world. Today, I’m reporting from the Atlantic rainforest of northeastern Brazil. This region, in the southeastern corner of the state of Bahia, once produced much of the world’s chocolate. Then some things happened that dropped the bottom out of the cacao market. First came mass plantings of cacao in South Asia and Africa. Then arrived the development of artificial chocolate flavor (today, most mass-produced chocolate has as much soy oil and artificial flavor as it does cacao). Then a fungus called Witches’ Broom, which grows naturally on wild cacao in the Amazon, found its way to Bahia. In the Amazon, cacao trees are sparsely scattered in the thick forest, making it unlikely for a spore of Witches’ Broom to find a host. But in Bahia the cacao trees are grown in thick monocultures, so close together they almost touch. There, a single spore can quickly produce 90 million more. Under these conditions, an epidemic of Witches’ Broom ensued. The Bahian chocolate economy crumbled. Much of the land was abandoned, and much was cleared for cattle ranching – a practice that can quickly destroy the jungle’s thin soils.

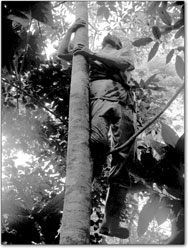

Meanwhile, a Swiss man named Ernst Goetsch moved to the area and began buying the most degraded – and therefore the least expensive – land he could find. He began planting forests, modeled after the ecological succession that would naturally occur there, but accelerated by what he calls “interventions,” also known as selective pruning. In a natural ecosystem, a barren piece of land would first be occupied by colonizing plants, which can live in thin, dry soils and full sun. As the colonizers die and decompose, soil is built up, and other plants can take their place. Ernst calls this the “accumulation” phase, because plants grow thickly and rapidly, adding much more organic matter to the soil. The final phase Ernst calls the “abundance” phase, characterized by many levels, from the high canopy, to the intermediate level and lower growing, shade-dwelling plants. Ernst manages his growing forests with a machete, cutting young trees to make room for others, pruning branches and leaves to accelerate the accumulation of organic matter in the soil. As he plants each stage of ecological succession, Ernst uses edible species whenever possible. Pineapples, okra, beans, melons, greens, manioc and corn, for example, make good colonizers. Guava, banana, citrus, soursop and passion fruit make good accumulators. Brazil nuts, cacao, mango, jack fruit, rubber and avocado are good species for the mature forests. Ernst’s first plantings are now 20 years old. His man-managed forests are cool, diverse, welcoming places to be, with thick, rich, soil, alive with fungus and worms and bugs, and rarely any Witches’ Broom. His cacao beans, shade-grown and organic, command a higher market price than regular cacao beans. He also does well selling dried pineapple and bananas to overseas markets. Ernst eats almost exclusively from his chocolate rainforest, although he does admit to buying cheese. “As a Swiss,” he explains, “I would lose my passport if I didn’t eat cheese.” A spry 58 years old, he slithers up trees and crashes through the canopy, sending down pruned branches to become the future soil of the chocolate rainforest. I pass some of Ernst’s forests as I walk toward Gandu. The birds in them seem to chirp more – no surprise considering all the fruits and nuts. Soaking wet, I experienced a brief moment of peace and bliss, during which I didn’t want to be anywhere else, didn’t feel sorry for myself for not being with the rest of the gang, still sleeping, with plans to roast cacao beans and make chocolate that day. A VW van stopped on the road. The driver offered me a ride to Gandu. •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel