| ||

More than a century at the sawmill

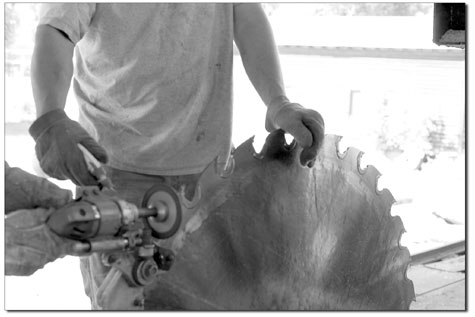

by Jeff Mannix He has no business card. There’s no sign out front, no advertisement in the phone book, no Web page – in fact, no company name. Yet Ronny Yeager owns and runs one of the state’s remaining family logging and sawmill operations, and it is within a short walk from downtown Durango. In operation since the early 1890s, it has all the business it needs. So much for the information age. Although seldom noticed, lumber is everywhere. Lumber frames, floors, roofs and sides our homes, builds barns, holds windows, makes stairways, forms concrete, is the stuff of furniture, fills doorways, reaches toward the promised land atop churches. Lumber is the only reason we need a fire department … well, almost. It’s so ubiquitous that we seldom pause to see it or contemplate where it comes from. Just as our food comes from the grocery store, lumber comes from a lumber yard. End of story; it’s not scarce, so why bother to know how it’s made or where it really comes from? For the epicures of wood, however, lumber comes from a large variety of trees, quality grades and sources. Not just any board will do for some, just like beef or tomatoes, a large chasm exists between corporate product and locally grown and harvested. And for those enthusiasts, Ronny Yeager is the go-to guy for only the best. Besides taking time to compete in nordic skiing in the 1972 and 1976 Olympics, Yeager has logged and sawed wood in La Plata County since he’s been old enough to get out of the way. His dad, Barney, and Barney’s five brothers, toddled around the woods with their father, too. So the Yeagers have been loggers and sawyers for more than 100 years, building a reputation, legacy and structures that Ronny is proud of and three generations of customers are loyal to. Yeager is a one-man operation, with seasonal and occasional help from his son and a cadre of young men who feel that they were born in the wrong generation, boys who were men before they were of age, chaps who love hard work, long hours, danger and reflex, the smell of earth and sawdust, and the sublime feeling of producing something that few ever have the opportunity to learn or master. “These kids who’ve worked for me, I make sure they all get a house of their own, a sturdy house of logs that’ll last ‘em a hundred years,” Yeager says matter-of-factly. “We give away firewood to the old people; we give away sawdust to the horse people; hell, I give away more than I sell,” Yeager laughs with a gleam of satisfaction and a self-depreciating chuckle, “It’s a wonder I’m still in business.” Yeager is one of those guys who you wonder where he finds the time to do everything he does. The raw material from which he makes raw material for houses comes from standing timber on private land in and around La Plata County. When he’s logging, he’s up before the sun, in the woods with his massive chain saw, centipede-like log skidder and his 18-wheel truck and log trailer. He takes between 20 and 30 truckloads of logs back to his Durango sawmill each summer, enough to make one or two 2,500-square-foot log homes or four or five conventionally built frame houses. And when he’s not filling an order for lumber, he finds a lot and builds a log home to sell. “We have some of the finest trees for structural logs and lumber anywhere in the country down here,” Yeager boasts. “When they’re graded, the licensed graders, who sometimes come down from as far away as Washington State, just can’t believe the quality.” It’s almost as if Yeager is speaking about prized race horses or the home of the space shuttle; he loves this wood like family. The Yeager Sawmill sits on 2 acres across from the Exxon station on U.S. Hwy. 160 West. It’s dominated by a stack of logs 40 to 50 feet long and between 30 to 50 inches in diameter. “Show loads,” he calls them with a laugh, “the kind you park up on the highway for people to admire and gawk at.” But once you get over the immensity of this pile of “sticks,” the eye rivets on the ancient sawmill, a covered contraption with a carriage to carry the gargantuan logs into a circular saw blade that is 45 inches in diameter with curved teeth that could fit a man’s forearm in each radius. It’s powered, both saw and carriage, by a 500-horsepower V12 diesel engine connected by ingeniously handmade power drives, belts and hydraulic hoses, all controlled at the sawyer’s seat, not 30 inches from the whirring blade. Big corporate sawmills have killed off most of the family sawmills that were found in every rural town a few decades ago, just as big-box retailers have displaced locally owned clothing, grocery and hardware stores. The giant sawmills use band saws to minimize “kerf” waste, the sawdust made from the cut, but Yeager still uses the circular blade weighing 180 pounds that his grandfather used in the 1890s, and he’s proud of it. The circle saw, as it’s called, is a beautiful piece of steel that gets tuned like a pressman coddles his printing press. As it cuts through a dense log it wants to get hot, and heat warps steel. Water is dripped on the blade, but the skilled sawyer knows how to run the log through the cut so perfectly straight that the blade stays cool to the touch and the boards measure precisely. “The saw blade runs at between 500 and 750 revolutions per minute, and at that speed it has what we call tension – it stands up straight,” Yeager explains as his hands caress the shiny surface. “Without this tension, the saw wobbles, gets hot and has to be removed, laid on an anvil and pounded straight again.” The dozens of fingernail-sized teeth are made of hardened carbide steel and have to be sharpened after each day’s use and replaced if the saw hits a piece of metal in the log, which is common enough for Yeager to have a vast collection of nails, spikes and wires, which he says are usually out of sight deep within the log. Asked if he can identify where the various boards come from, Yeager says, “All I have to do is take some sawdust or a sliver of the wood and taste it. Hey, I’ve been at this for 50 years.” •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel