| ||

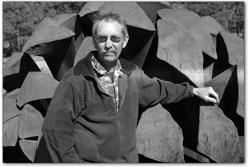

Larger than life by Jules Masterjohn One sometimes wonders how it is that we develop the tastes and preferences that we do. I have come to understand that because of growing up in the hinterlands of Minnesota, I like really big art. In towns all around the state, strangely large sculptures exist. Paul Bunyan and Babe the Blue Ox, both sculpted in concrete, stand two stories high in Brainerd, a northern town. In Fergus Falls, a favorite prank by graduating teens is to benignly adorn the 25-foot concrete otter that stands motionless in a city park. In Rothsay, a major tourist attraction is the largest prairie chicken in America, weighing in at 9,000 pounds. My taste for large sculpture was born from my early exposure to a most unusual form of upper Midwest folk art. Two famous makers of the fine art version of large-scale creations are the European-born artist team of Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen. Their gargantuan likenesses of ordinary manufactured objects, such as “Spoonbridge with Cherry,” installed in the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden at the Walker Art Center, can be seen in major cities the world over. Thirty feet long, its 8-foot-diameter red cherry sphere spouts a stream of water from its stem, which falls into a pool of water surrounding the spoon. In our region, we need only travel to Las Vegas to see one of their huge creations, where the monumental work “Flashlight” is permanently installed outdoors at the University of Nevada. Fabricated on the East Coast, trucked across the country on a double-long semi and installed in 1981, the black steel column now stands 38 feet tall and weighs in at 74,000 pounds. It shines downward into a pool of illuminated water giving the impression that it is the sole source of power for Vegas’ neon world. Closer to home, the work of Durango artist Dave Claussen can be described as a bit Oldenburg-esque. Though he is not reproducing man-made items, Claussen is inspired by objects relevant to our region’s cultural sensibility: nature. Two monumental, welded-steel sculptures created by Claussen stand as welcoming objects at the entrances to the new residential development, Edgemont Highlands. The 6000-pound “Pine Cone” sits along the roadside, resting among the tall pines as its normal-sized kin do, but with much more presence. Claussen’s art affair with huge bits of nature began with a call from Highlands’ developer and builder Tom Gorton. During their initial half-hour conversation, Claussen and Gorton rolled around enough ideas that the huge pine cone fixed itself in the artist’s scope. Claussen was inspired to call attention to the small and often overlooked natural structure. “We see these things all the time, and we just breeze by them.” In order to recreate it realistically and on a huge scale, Claussen had to “get intimate with a pine cone.” He began his artistic investigation into the anatomy of the conifer flower by picking up every one he saw and inspecting its form. He discovered that they are all subtly different. So he chose one that appealed to him, took it home, and cut it in half. This dissection gave him the initial idea to build the sculpture in quarter sections and weld them together when all sections were complete. However, after considering the technical aspects more carefully, he abandoned that approach given the physical reality of stabilizing four 3000-pound sections while welding them together. So, he went back to the drawing board to rethink his fabrication process.

In order to recreate it realistically and on a huge scale, Claussen had to “get intimate with a pine cone.” He began his artistic investigation into the anatomy of the conifer flower by picking up every one he saw and inspecting its form. He discovered that they are all subtly different. So he chose one that appealed to him, took it home, and cut it in half. This dissection gave him the initial idea to build the sculpture in quarter sections and weld them together when all sections were complete. However, after considering the technical aspects more carefully, he abandoned that approach given the physical reality of stabilizing four 3000-pound sections while welding them together. So, he went back to the drawing board to rethink his fabrication process. The construction solution that resulted was to build the way nature works – from the inside out. Claussen constructed an A-frame structure on which to attach the individually welded “scales” – the small, angular, knobbed forms that define the pine cone shape. The scales were joined onto the frame using a concentric, spiraling pattern, as is Mother Nature’s preference. During the process of building “Pine Cone,” Gorton mentioned that he wanted another large-scale sculpture for the other Highlands’ entrance. Claussen spent time with Dolores-based landscaper and artist Linda Robinson, walking the Highlands’ property and discussing the possibilities for the next sculpture. “As we walked, I picked up lots of oak branches. When I got back to the studio, I hot glued them together.” That was the beginning of “Oak Branch,” Claussen’s newest mammoth, site-specific sculpture, a 32-foot welded steel branch with seven leaves, which reclines on the ground. Created in a somewhat realistic manner and located at the edge of the pines, the sculpture looks like an actual tree. One day while Claussen was doing some fine-tuning on “Oak Branch” at the site, a fellow walked over, chainsaw in hand, to cut it up. “He thought it was a fallen snag,” bemused Claussen. This is just the kind of good fun that keeps Claussen happy as an artist. He takes delight in the fact that the Highlands’ project manager, Kim Lawrence, whose office is located at the Highlands development, refers to it as the “branch office.” Fun is important to Claussen, and it is evident in his sculpture – big, playful and energetic. He says that he doesn’t do anything if it doesn’t contain the concrete possibility of a good time. Even his 7-foot-long pine needle cluster that tops the Edgemont Highlands entrance sign has a bit of whimsy in it, just by being so amped up in scale. A satisfied artist these days, with a new project on the horizon that came directly from his success with “Pine Cone” and “Oak Branch,” Claussen beamed, “I can’t imagine a better place to display my artwork. It is great exposure.” • To view Claussen’s sculptures, travel east on County Road 240 about 6 miles and the entrances to Edgemont Highlands are on the left.

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel