| ||||

The plight of 'El Inmigrante'

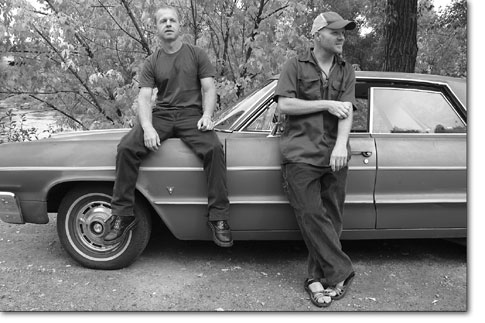

by Shawna Bethell ine hundred and three migrants dead in Texas; 834 migrants dead in California; 353 migrants dead in Arizona. They are numbers without faces. No identities to relate a story to, no human connection to incite consciousness in those living their 9-5 middle class lives. Until the death of Eusebio de Haro Espinosa, the numbers were relegated to headlines in border town newspapers and used in discussions of the illegals who come to this country to “take jobs from American people.” But living in Tucson and reading these headlines, local filmmaker John Sheedy became inspired to put a face on the numbers. It was a “humanitarian crisis that needed to be documented,” he said. After securing funding through Executive Producer Rick Carlson, Sheedy contacted fellow Durangoans and filmmakers David and John Eckenrode and the three men embarked on a journey through murder investigations, immigration politics, and the ugliness of racism to create the documentary “El Inmigrante.” The film just earned the award for Best Documentary at the 2005 Harlem International Film Festival. “El Inmigrante” personalizes the issues surrounding Mexican-American border relations by depicting the story of Eusebio de Haro Espinosa a young man who was shot from behind by an elderly white man in the borderlands of Texas. The murder and the miscarriage of justice surround ing the murder made the news, somehow preventing Eusebio from being just another dead Mexican in the desert. Sheedy and the Eckenrodes took the news story and created a poignant expose by spending time with the family of Eusebio and learning why so many Mexican people are willing to risk everything to get to America. They talked to the border patrol, and they talked to the vigilantes. They took a complicated political issue and made it human. “This is a powder keg ready to blow,” said David Eckenrode of the immigration issue at large, and the tension on the border is well depicted in the film. “Private citizens should not be allowed to patrol the border. Eusebio being shot was a matter of paranoia.” Sheedy further explained. “People have always crossed the border, but with NAFTA and the crash of the peso in 1994, more and more people are coming across.” Both men feel that September 11th added fuel to an already volatile situation causing vigilantism to become more rabid in its determination. Sheedy also said a funneling effect has been created as heightened patrolling in some areas has caused an increase in numbers of illegals crossing in more dangerous places. The heat of the desert and lack of water have also taken their toll on the lives of immigrants and intensified the humanitarian crisis the filmmakers hoped to depict. And then there are the coyotes, people who charge desperate illegals large amounts of money to be guided across the desert and into a city where they can find work. But both Eckenrode and Sheedy explained in frustration the “gangsterism” that has been created out of the lucrative practice. “Instead of shipping illegal drugs, they are shipping illegal humans,” said Eckenrode with disgust, and often, the people are just taken advantage of. Stories of migrants crowded into vans, locked in sheds, left in the desert with no food or water are common place, but the risks are worth it for millions of Mexican people who try to reach America to work and create a better economic position for themselves. “The issues kept getting so complicated,” said John Eckenrode, who has left Durango for4 Portland, Oregon. “There are so many valid points (in the dialogue of immigration) that by halfway through filming I didn’t know how I felt about anything anymore.”

“Instead of shipping illegal drugs, they are shipping illegal humans,” said Eckenrode with disgust, and often, the people are just taken advantage of. Stories of migrants crowded into vans, locked in sheds, left in the desert with no food or water are common place, but the risks are worth it for millions of Mexican people who try to reach America to work and create a better economic position for themselves. “The issues kept getting so complicated,” said John Eckenrode, who has left Durango for4 Portland, Oregon. “There are so many valid points (in the dialogue of immigration) that by halfway through filming I didn’t know how I felt about anything anymore.” Many of these issues are brought out in the film. The ugliness of American racism, the possibility of an open border, the need for Mexico to take care of its own people so they do not need to cross the border. What it does is make people think. Exactly what the three producers had hoped. “More than anything we wanted to create dialogue, and that seems to be happening. At the showings in New York, there was always discussion,” said David Eckenrode. The film debuted at Loew’s Magic Johnson Theatre in Harlem and played the next day at Columbia University. After such an emotional struggle to get the story they wanted to show the world, Sheedy and the Eckenrodes could finally enjoy the fruits of their efforts. “It was great to see it up on the billboard at Loew’s,” said Sheedy. “You had War of the Worlds and all the other movies and there we were, ‘El Inmigrante.’ But you are also wondering, ‘That’s cool, but what’s everybody else going to think?’” The film was one of 50 chosen out of 500 submissions to the festival, and considering this is their first submission, the film team was honored to be accepted, let alone win Best Documentary. But none of the three feel their journey is complete. They are submitting to several other festivals and a few film distributors, and while they hope it goes big, they each feel strongly that they want to keep the film at the grassroots as well. That effort begins by taking the film back to San Miguel de Allende, a community near Eusebio’s hometown, as well as other cities in Mexico. It is important to them that the family see the finished product and to take the story to the people it affects most. There was a great deal of respect between those making the film and the family whose trust they finally earned. “Pasiano, Eusebio’s father, has a lot of wisdom,” said Sheedy. “He felt that it was destiny. He trusted that we should be there to tell Eusebio’s story.” When the film team took “El Inmigrante” to New York, Pasiano was pleased. One of the quotes that begins the journey of this powerful documentary comes from the father sitting at the kitchen table, wife beside him, hands clasped before him. “Maybe there won’t be justice, but maybe there will be consciousness.” David Eckenrode and John Sheedy will both continue with their passion for film, but both feel that it is time for something less heart-wrenching. Eckenrode is working on a feature film that he describes as “mountain gothic,” and Sheedy said he would like to create something along the realm of magical realism similar to “Like Water for Chocolate.” “I would definitely be interested in doing another documentary for social change,” said Sheedy. “But the subject has to find you.” Eckenrode agreed. Until that time, they will continue to market “El Inmigrante.” With that in mind, a lunchtime fundraiser will be held at Cocina Linda on Sunday Oct. 9 to help Sheedy and Amy Iwasaki take the film to Mexico for the showing at San Miguel de Allende. The two will also be taking school supplies and other needed items to members of the communities they visit. •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel