|

|

||||

|

The healing power of

creativity

by Jules Masterjohn Teacher and artist Adriana Diaz writes in her book, Freeing the Creative Spirit, “Creativity is the real magic of our universe. It is the shape of our courage and the force of our souls.” The strength of Diaz’s affirmation can be seen and felt in the artworks created by women who have something to share about the topic of eating disorders. Not a usual subject of inspiration for most artists, each of these individuals has a unique relationship to the disorder’s spectrum: some in recovery, others active in the disorder, those proactive about the topic and those bearing witness to the painful condition in someone close to them. For all the women who have created artwork on display in the “Eating Disorders Awareness” exhibit, not only the creation but the sharing of the artwork is a touching and courageous act. According to exhibit organizer Kathryn Catsman, an eating disorder grows out of a sufferer’s inability to express his or herself, to find a meaningful place in the world. “There is no doubt in my mind that anorexia is a metaphor for a person’s desire to just disappear because there is no place of comfort for them.” Catsman wants to bring awareness to the underlying emotional causes of the disorder, which often include feelings of inadequacy and low self-esteem. Most often, people suffer in silence, their malady unknown to even their closest friends and family members. Catsman, who has four drawings in the exhibit, has a personal interest in the subject. “This topic is a passion of mine, not only because of my own experience but because I have seen people suffer and die from this.” Her hope is that the exhibit will bring awareness to what she sees as a rapidly growing problem. Gone are the days when anorexia and bulimia were the only conditions associated with eating disorders. “Today,” Catsman said, “there is a broad continuum of behaviors that includes overeating, obesity, purging, over-exercise and orthorexia, an obsession with healthy eating.” The condition, usually associated with girls and women, manifests itself as a preoccupation with body image, a focal point of our appearance-driven culture. It is her hope that this exhibit will prompt conversations among parents, children, friends and coworkers so that those suffering silently might reach out to someone they love and trust. Writer Molly J.A. Childers, who has three collage works in the exhibit, agrees. “I want people to look with an open mind and with great compassion. I feel that this problem is so prevalent in society that many will be informed. To me, the disease is one of silence … so much is left unsaid.”

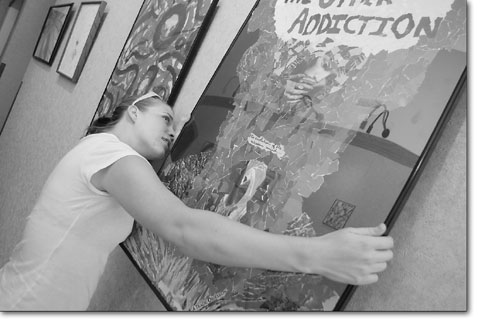

Childers has done her part to break the silence. Her recently created mixed-media collage, “The Book of The Burning Rose: How I Learned to Speak the Language of Vanishing as a 13-year-old Anorexic,” stretching over 3-feet long, is an “honest, aching exploration of the root causes of this disorder.” Childers weaves her talents as a writer with her recently found love of the visual arts. Powerful, poetic phrases, like “the serpent in this savage garden, none other than myself,” penned on fragments of paper with burnt edges and floating on a black background, give an overall chaotic feel to Childers’ narrative. “The burning book is meant to look fragmented, like many things are missing.” Now almost 20 years past her struggles with anorexia nervosa, Childers is still exploring her healing process through art and writing. “Making art gives me a container for my emotions, a place where I have some type of control over what I’m feeling, maybe its poor self esteem. I can write the feelings down, express them in color, and get them out of my heart.” Collage works are prominent in the exhibit, perhaps because the collage process is direct and immediate which lends itself well to expressing emotion. Amber Sokoll, a recent Fort Lewis College graduate, created a large-scale collage using small bits of torn paper in red, gray and black. The overall effect of her collage, “The Other Addiction,” invites closer inspection by the viewer. Another collage in the exhibit, “Listen to a Girl,” a gathering of thoughts written on white fabric placed on a red background, poses important connections between body image and self-esteem. Created by girls, teens and women who participate in Project Girls, statements like, “Why do I think only thin women are deserving of respect?” and “I am dating a chubby guy and being made fun of,” speak to the biases and pressures young people face in our image-conscious society. Red is a predominant color in the exhibit, perhaps symbolizing a sea of rage, the fires of passion or the blood that courses through our veins. Red is a color difficult to overlook, not only due to its optical properties but also for its references to intense emotions. Local artist and art teacher Margaret Pacheco’s mixed-media work, “The red painting,” was created out of her need to express how grief and the emotional traumas of war are deeply connected to many disorders. Her painting is in honor of all who suffer around the world. This small piece draws the viewer into her story by isolating three small, line-drawn figures, a family, within a broad field of red. Pacheco believes in the transformative power of the creative process. “It lifts us up from where we might have lain forever. I often tell students that in art they have a new or additional voice through which to speak to those who may have never heard them otherwise. This added voice transforms them and the people around them. The creative process, whether it is painting, writing, dancing or playing music provides a way to reflect and communicate. We find our minds occupied with trying to create, out of all of our life experiences, something beautiful.” •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel