| ||

Blood on the snow

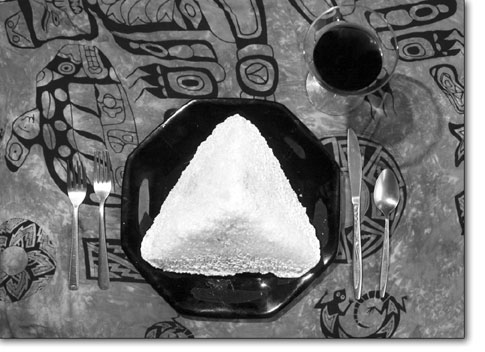

by Chef Boy Ari The recent food issue of the New Yorker contained an article titled “Two Cooks,” written by Adam Gopnik. One of the featured cooks was London’s Fergus Henderson, who has achieved notoriety for presenting the innards and unlikely extremities of animals in dishes like pigs’ ear soup, ox hearts with pickled walnuts and rolled spleens. The other of Gopnik’s two cooks was Alain Passard, the founder, owner, artistic director and head chef of Paris’ legendary L’Arpege. While Henderson pursues “nose to tail eating” with bold inventiveness, Passard is finished with red meat, having thrown all of his artifice into vegetables, which he considers a vast and barely-tapped frontier. “It is,” he says, “as if I had this friend standing next to me for 30 years in the kitchen, and I never even said hello!” Passard’s cuisine vegetal can be extravagant and complex, as in a chocolate avocado soufflé or a three-layered nasturtium soup, or it can embody the elegant Zen simplicity of a perfectly cut tomato, salted and drizzled with balsamic vinegar. Passard is quick to point out that behind every deft gesture of the knife in his kitchen, there were a thousand deft gestures in the garden. Much of the produce served at L’Arpege comes from Passard’s organic vegetable garden outside Paris, including the beet that Gopnik briefly mentioned in the following passage: “… the beet is cooked in a crust of gros sel, as duck and lamb have been for centuries, and then the crust is broken with a flourish and the beet is delicately sliced and served, with a light jus, as the main course.” It would be mine, I decided. Oh yes, it would be mine. A Google search for gros sel turned up many pages in French, which did not help me — if I spoke French I would already know what gros sel means. I did however find many gushing references to Passard’s salt-roasted beet in web chat rooms. Eventually I realized and easily confirmed that gros sel simply means “course salt.” The only recipe that came close to what I was looking for was a salt-roasted beef dish I found on epicurious.com. I figured that was close enough, since beef and beet differ by only a letter. Then I received a response to a desperate e-mail I’d sent to Marlena Spieler. Spieler is a roving food columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle, and I had read her mouth-watering recent dispatch from L’Arpege, where she encountered the famous beet. In her response to my e-mail, Spieler confirmed that the beet was indeed entombed in Fleur de Sel de Guerande, a very expensive hand-harvested sea salt from Brittany. The beet was buried near the top of the salt mountain, she wrote, “about a third of the way down. To serve it they tapped around the top of the mountain and lifted the lid off, then fished out the beautiful beet, brushed off the excess salt grains, and voilà: served it in thin wedges with a drizzle of 50-year-old balsamic.” Perhaps this all-important aged balsamic vinegar is the jus Gopnik mentioned. Buoyed by this key information, my experimentation continued. Every night for a week, it was salt-beet for dinner, salt-beet for dessert, salt-beet for breakfast. Following the Epicurious.com recipe for the gros sel crust, I mixed 4 cups coarse salt with a cup of water, stirring until it reached “the consistency of wet snow.” I then built a sturdy salt base for my beet in an oiled baking pan or cast-iron skillet. I placed the beet, whose leaves had been clipped at the base and tail had been snipped below it’s swollen round part, firmly upon its pedestal of salt, and packed more wet salt around it. If you want to get fancy, use a putty knife to shape and smooth the salt as you see fit. Bake for an hour at 300 degrees — for a larger beet, bake for an hour and 15 minutes. At this point, the pyramid will have hardened into a granular shell. Remove the beet from the oven and let it cool. Set it on a sturdy table and use a hammer and chisel to open the top of the salt pyramid. Remove the cap to reveal the beet in its cavity of salt. Brush off any salt that might cling to the skin, cut the warm beet into wedges and drizzle with aged balsamic vinegar. The balsamic lends its grapey sweetness, its subtle forest-like complexity and piercing acidity to complement the salted sweet earth tones of the beet, rich as blood and hearty as meat.

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel