| ||

Learning to love Thanksgiving

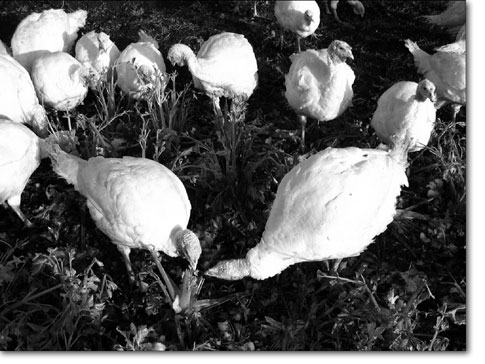

by Chef Boy Ari No holiday leaves me as conflicted as Thanksgiving.An autumn celebration of the harvest, Thanksgiving calls our attention to the gratitude we should focus on the people, the earth, the confluence of sun and rain, and all the other elements of the universe that conspire to bring life-sustaining and delicious food to the table. Thanksgiving is a long and ornate way of saying grace, which some people say before every meal – a practice I support. When you say grace, or “blessings on the meal,” or “rubadubdub thanks for the grub,” that meal becomes a Thanksgiving. But there’s a dark side to the holiday known sardonically by some Americans, especially American Indians, as “Genocide Appreciation Day.” The pilgrims gave thanks, so the story goes, to the Wampanoag Indians for helping them survive their first winter in the New World. The story doesn’t usually report that this was part of a necessary Indian ass-kissing phase in the early years of colonization, when the fragile ranks of the Pilgrims were vastly outnumbered by their hosts, who could have wiped them off the face of the map without trying. Historians who dig beneath the revisionist veneer of Thanksgiving legend report that the original three-day feast of 1621 featured as much guarded suspicion as camaraderie, and any crying and hugging that might have gone on seems to have spread more smallpox than love into the native population. In a sermon at Plymouth two years after the original Thanksgiving, a Pilgrim preacher named Mather the Elder thanked God for smallpox, which had by that point wiped out many of the Wampanoag. A few years later, the Pilgrims and what was left of the Wampanoag were fighting each other in King Philip’s War, which by today’s standards would be considered more a massacre than a war. Since then, many American Indians have cursed the hospitality of their ancestors. This “mistake” is what the invasive Americans gave thanks for. The American Turkey Growers, meanwhile, give thanks for the one and only day of the year that keeps their industry afloat. Although there was not a single turkey at the original Thanksgiving, the Norbest Turkey Co. (one of the nation’s largest) carefully notes on its website that “History associates turkey with the first Thanksgiving feast celebrated by the Pilgrims in 1621.” True enough, but delicately misleading. More accurate would be to say that “History incorrectly associates turkey with the first Thanksgiving ... .” I have nothing against the turkey itself. The turkey is as native to America as Native Americans. Benjamin Franklin was such a turkey fan that he pushed for the turkey, rather than the bald eagle, to be our national bird. But the turkey on your Thanksgiving table is a far cry from the bird that earned Franklin’s respect. “Turkeys are more altered by breeding than any other poultry,” says Sarah Stokes, who raises free-range turkeys in Missoula, Mont. “They’ve been bred to have the largest breast in proportion to their bodies. The industry-standard turkey, the Broad Breasted White, can’t even breed naturally because of the way their bodies are shaped. It’s all done by artificial insemination.” Still, she says, turkeys are pretty cool. They are much better foragers than chickens, consuming a larger proportion of forage to grain than a chicken would, given the chance. “The turkeys really seem happy,” she says. “They follow you around, curious. Turkeys are more interesting than chickens.” This is something that Stokes, who also raises free-range chickens, can say with authority. “Another interesting thing they do is eat a lot of rocks,” she says. The rocks lodge in the gizzard and help grind up the forage. “Some of the rocks are the size of marbles.” Currently, Stokes’ turkeys are grazing upon the unharvested produce at a nearby organic farm. “First they were eating salad mix,” she says. “Then broccoli, cauliflower and cabbage, now celery.” That’s practically grounds to market them as pre-stuffed. Perhaps finish them off on a diet of breadcrumbs … . Stokes is donating 100 of her turkeys to the local food bank so that low-income people can celebrate “Genocide Appreciation Day” with high-quality meat. There is poetry and healing in this act of giving away prime birds to those who otherwise might not be able to afford a good meal. That’s worth giving thanks for. It’s only a meal, but it’s a gesture. And gestures have a way of spawning. No conflict for me there, thank you very much. Especially since I’ll be sorting out my conflicts by calling it a harvest feast, and celebrating it Sunday. I sure would like to have one of them turkeys, though. •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel