| ||

Poplar Popsicle Seeds

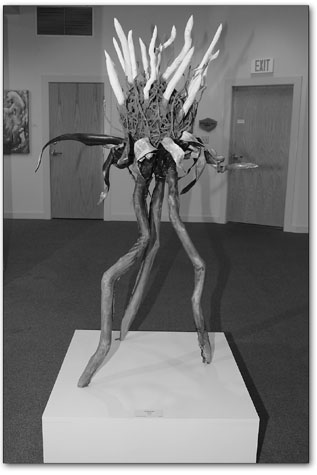

by Jules Masterjohn There are differing schools of thought on the artist’s need to articulate visual ideas in words. One “old school” perspective claims that no verbalization or writing is necessary because “the work speaks for itself.” We, the viewers, are left to fend for ourselves, interacting with the artwork without mediation by the maker. Another perspective suggests that the artist be an authority on his or her work, able to articulate ideas, working processes and artistic intentions. In today’s competitive and intellectually oriented art world, most often artists are required to produce such a written testimony, known as an “artist’s statement,” to accompany their work. This raises the ante for artists, demanding that they not only be communicators in a visual language but also in a written one. Such a statements can offer a much richer perspective on an artist’s work and process. The current exhibit at the Durango Arts Center, “Polar Popsicle Seeds,” is an example of the articulate use of artists’ statements to inform and enhance a viewer’s experience. Three distinct styles of art fill the Barbara Conrad Gallery. Occupying the center of the room are Sandra Butler’s sculptures, which act as an interface between paintings by Lauren Carroll and Jazz Morgan. Butler’s curious mixed-media pieces clearly reveal her interest in botanical forms. The sometimes huge, almost Paleolithic plant forms suggest an awareness of nature’s life cycles as well. Butler’s artist statement begins, “I see tall flowers that continue to grow toward the sun even after they have tipped over from their own weight. I see seeds that have learned to fly in an attempt to propagate far from the plant source. I see metaphors for my own physical and emotional processes through these observations. The inspiration for this artwork comes from the idea that my inner world and outer world are reflections of each other.” One of Butler’s larger pieces, “Thistle,” greets visitors near the entrance to the gallery. Standing over 4 feet tall on a tripod base of tree limbs encased in rawhide, “Thistle” is topped with a wire ball encrusted with purple sand and adorned with white wooden spikes, protectively piercing the air. This piece has an animated quality that liberates it from the more grounded of Butler’s structures in the exhibit. It has sprouted legs to propel itself, or perhaps it has grown roots to help hold it more securely. Either way, this tripod form is an evolutionary development from the more usual barnacle-type bases Butler has used for her free-standing sculptures. “Succulent,” a phallic-shaped tubular form reminiscent of a gargantuan stamen in a desert bloom, has its top edge splayed open like a peeled banana, exposing the interior’s empty space. Once turgid and full, now a partially flaccid vessel of spent energy, “Succulent” suggests a lamentation for something lost. Hidden in the sculpture’s strong verticality lies an intimate fold of rawhide that ascends the sculpture’s height, suggesting a co-mingling of masculine and feminine qualities. Another piece in the exhibit that shows potency within interior places and suggestive folds is the painting, “Cornered” by Lauren Carroll. The origami crane, Carroll’s subject in this and two other still-life paintings, is a symbol of peace and reconciliation. “Cornered” pictures a folded paper crane delicately painted in pinks and reds, positioned in a corner space, facing out at the viewer. Her artist’s statement explains, “When I make art, I delve into topics that are entrenched in my own life but universal in the human experience, such as fear, abandonment and escape. The objects in my paintings symbolize these human experiences and emotions. I want my paintings tapping issues and associations from the viewer’s life, so the work is personal to each individual.” There is a sense of imminence in “Cornered:” The crane is about to fly away, released from its defensive position. As it flies away, it will turn into a rising phoenix, symbolic of overcoming adversity through transformation, of life anew. Carroll’s realistically painted portraits of these simple folded forms are not so simple. There is a psychological energy that vibrates within each, encouraging the viewer to investigate the objects presented in a deeper way. Jazz Morgan’s oil paintings embody energy as well. Her “Inua Crossing Series” paintings depict polar bears in combination with other forms, suggesting that spirit is imbued in all objects, an Inuit Eskimo belief in animistic spirituality that gives power to all things. In Morgan’s world, the rock and the polar bear have equal impact. She writes, “Concentrating on the essence of nature’s energy, the work suggests rather than defines. By isolating gesture, using singular focus, organizing color and direction around the concept of Zen empty space, the work resonates with the energy of Haiku.” Morgan’s approach to painting lingers close to the Abstract Expressionist attitude, where the action of painting, the recording of the physical mark, is a supreme undertaking. I get lost in the small marks of her compositions, thoroughly enjoying the way oil paint fell off the brush onto the canvas in a 2-inch square area of “Inua Crossings Series 5.” Morgan’s brush strokes hold the energy she refers to in her statement. Her spontaneous method is most obvious in the expressive brush strokes she uses to represent “fleeting energies;” there are spiritual matters being wrestled with on these canvases. Like Butler and Carroll, Morgan’s artist’s statement honestly reveals her reasons for art making: “The struggle to connect what is seen outside and what is felt inside is what the work is about.” “Polar Popsicle Seeds” is on display at the Durango Arts Center through Nov. 26. Gallery hours are 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., Tuesdays – Saturdays.

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel