| ||||

A shooter in the Great War

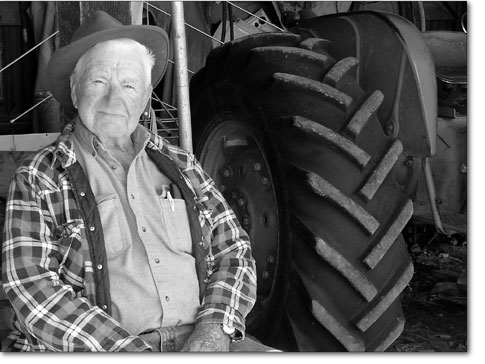

by John T. Rehorn In a place called Bondad, his house is easy to find on national holidays like this Friday’s Veteran’s Day — it’s the one with the Star-Spangled Banner flying on a pole by the front door. Otherwise, the man gives no hint that he served in World War II. Lawrence Craig, a photo reconnaissance pilot during the war, has heard his share of war tales – he’s mostly skeptical. “People like to hear sensational stories,” he said, “but the war was won through the efforts of thousands and thousands of men and women working together.” He would be the last one to add his to the stack of “war hero” stories. “I’d rather emphasize the contributions I made to the reconnaissance organization after I came back from overseas,” he prefaced. “I was the one that developed the first training manual for reconnaissance pilots.” Upon his return to the United States from the North African theater, Craig helped to bring training for “recon” pilots to the level of fighter and bomber pilots. To understand the significance of his contribution, one must understand the dire need at the time for such a training program, and that’s where Craig’s story comes in. America was swept into the war after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. Craig had been working at the Smuggler mine in Telluride when he decided to enlist. It was simply the thing to do, he said. He joined the Army, but during basic training, he read of the opportunity to become a pilot for the Army Air Corps and decided to give it a go. He aced the qualifying exam, finishing in the top 3 percent among airman candidates. Being a pilot didn’t ensure safety, but it kept one out of mud-filled trenches. Before he knew it, Craig was in Advanced Flying School at Mather Field near Sacramento, Calif. There, he learned the art of flight from none other than Hollywood actor Jimmy Stewart, an Army Air Corps flight instructor. After Craig learned flying basics, he was shipped to Colorado Springs to train in the P-38. “There was no structure to the training. We were to just go out and fly,” he said. “So we’d get up in the morning, fly around 500 miles out, land, drink some coffee, refuel and come back. That was routine. We’d go to Omaha, Amarillo, Oklahoma City, Albuquerque – just to use up hours.” The Lockheed P-38 was to become the all-around aircraft of the Army Air Corps. Capable as a bomber, a fighter and a high-altitude escort plane, it had a top speed of 414 mph and a cruising speed of 275. With a mix of hatred and admiration, German Luftwaffe pilots dubbed it the Forked-Tail Devil. The duo-tail design cost Lockheed engineers more than a few headaches to get it right. But by the time the P-38 matured out of its “awkward stage” in 1942, it proved to be an all-American star. With such power and speed at his command and a little bored by the Front Range landscape, Craig decided one clear morning to veer west for a bird’s eye view of his old stomping grounds. After all, he could get there and back with time to spare in this fine machine. He approached Durango from the southeast. If he had any notion at all, it was to get a nice look at the town from the air while he racked up training hours. Youthful mischief got the better of him and he opted not to throttle down as he made his descent. “I just let the old horse go,” he said. Coming in hot, Craig buzzed Main Avenue at less than 100 feet. The good citizens of Durango were treated to an up close and personal view of a P-38, that is if they were out on Main Avenue and looking up when Craig zipped over. When he was over Main, Craig said he could see the building tops of Second Avenue beyond his right wing. “There’s some who think that’s a great story and some who think that was a damn fool thing to do,” Craig chuckled. After a mere 50 hours of flight training – no evasive maneuver training, no emergency exit or crash landing training – 15 airmen, including Craig, were flown to Bristol, England. From there, the unseasoned pilots flew their machines to a base in Algiers, from which their missions would originate. “We didn’t have any guidance whatsoever except for bull sessions with guys who’d been in the mix.” Craig said. “We were all just a bunch of kids.” Rommel, the Nazi’s desert fox, was being chased up the coast out of Libya with the British troops on his tail. He was making for the Tunisian Peninsula, where he planned to cross with his troops into Italy. The Germans’ air power was in Tunisia to protect their retreat. “We had to fly over that area where there was a lot of concentrated German fire power. The intelligence officers would brief us on where there might be enemy antiaircraft or airplanes. They didn’t have all of the information themselves, but they passed on what they knew.” Craig’s first mission involved flying past the peninsula to photograph harbors and look for supply ships for the German forces. He also photographed strategic points on the railroad line, spots like bridges or switch locations. Bombers used the recon pilots’ photographs to identify and take out targets. Of course the Germans were none too keen about being snooped on – anti-aircraft fire and the Messerschmitt fighter were what recon pilots had nightmares about.

“I was scared,” Craig admitted. “In fact I was scared on all of my missions. In Riverside, Calif., they’ve got a P-38 museum, and part of it is photo recon. They have a sign that talks about the photo recon pilots flying alone, unarmed and unafraid. When I saw that years later, I thought, ‘That’s a lot of bull. Alone and unarmed, yes, but unafraid?’” Four missions later, Craig’s worst fears were realized. “I finished a mission and headed home, and I guess I had my attention more on getting my throttle settings and navigation right and didn’t look over my shoulder. It was a Messerschmitt 109 that picked me off. First thing I knew, the whole plane was on fire, inside the cockpit was like a stove. I felt a little shot on my shoulder like somebody might have punched me, and fire started boiling up. I didn’t much want to get cooked, so I released my safety belt and canopy and started to stand up and ‘whoosh,’ I 4 was out of the plane, floating. The suction just pulled me out.” Losing blood and consciousness rapidly, Craig pulled the ripcord of his parachute. Every 10th round in the Messerschitt’s machine gun magazine was a phosphorous shell. When the German pilot finished Craig’s P-38 off with a 30 millimeter cannon that ripped open his fuel tank, the phosphorus shell that followed ignited everything. The armor plate at Craig’s back saved his life. Craig said his doctor pulled out only plate fragments from his right shoulder – severe enough but not lethal. His right leg wasn’t so lucky; 10 machine gun shells entered there, chewing it up badly. Though he was horribly injured, he is amazed he survived. After floating to earth unconscious, Craig awoke to a group of men and boys, dressed in white smocks and turbans, standing over him. He reached for the message in his breast pocket that was issued to all the pilots. This is an American pilot, a friend to the Arab people, it indicated. “One old guy spoke to a couple of kids – one of them had a horse. They helped me up and got me loaded on the horse, no saddle,” he said. Craig drifted in and out of consciousness, held atop his mount by one of his rescuers. Past vineyards and orchards they walked for more than four hours. Coastal North Africa isn’t what one might think; the Sahara lay far to the south. As the sun was setting, finally they reached a road. By some twist of fate, a British patrol truck happened by almost immediately. Craig could only wave a feeble “thank you” to his rescuers. The Brits put him in the back of the truck and rushed him to a forward medical facility, akin to a M.A.S.H. unit. “That’s the last I remembered for quite a long time,” Craig said. He woke up three days later with surgery stitches in his shoulder and leg. That was the end of Craig’s war story, but not of his service. During his long recovery, he pondered about how much the Army Air Corps had invested in him, not to mention his plane. “When I first got in the war, they weren’t prepared,” Craig said. “The object was to get as many people into combat as possible. And the guys that were getting there got hurt.” With the idea in his head, Craig reported back for duty in Colorado Springs. He was one of the first recon pilots to return there from battle. The base’s assistant commanding officer endorsed the development of a bona fide training regimen for recon pilots. He directed Craig and Intelligence Officer Charlie Mee to proceed. “First, we sifted through all the regulations on the books at the time,” Craig said. Unfortunately, much of it was generic training. “The army had a requirement for so many hours of tent pitching – well that was out of line. We weren’t concerned with tent pitching or gas mask operation or things like that.” “We boiled it down to a schedule that could be fit into the demands of the Air Corps in furnishing replacement pilots,” he said. “We developed a training program that we could do in the time allotted with the equipment we had.” One thing they didn’t compromise on was flight time. Craig and Mee required a minimum of 250 hours with the P-38 after flight school, five times the hours Craig was required to put in. When all was done, Craig and his team put the Third Reconnaissance Command on an equal footing with the Third Fighter Command and Third Bomber Command. It meant that recon pilots would have the training to better keep themselves alive and their machines flying. Requiring many months of work and many miles of travel, their work established the proper training program for his fellow recon pilots. It’s the service that makes him most proud. Craig was awarded the Purple Heart and the Air Medal for Gallantry, but he attributes those honors to being at the wrong place at the wrong time. If you call him a war hero, he’ll shoot you down with a steely-eyed glare. But talk about his work in recon pilot training, and those same eyes sparkle. It was his way of rescuing some of his brothers-in-wings from a fate like his own, or worse. •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel