|

|

||||

|

Transcending the day to day with art

by Jules Masterjohn After a brief summer vacation, I have returned to writing with an invigorated perspective on my role as a weekly contributor to the local art scene. During my sabbatical, it became clear that I have a confession to make: I am a believer in the ability of art to transform the restless human psyche and thus heal the wanting world. This notion began to take form while I was studying art therapy in college. Way back then, art and music therapies were newcomers to the field of mainstream therapeutic psychology. Not too many years earlier, with the establishment of the National Endowment for the Arts in 1965, the American electorate decided that the arts were a legitimate and necessary component of a vibrant cultural climate and should be nurtured through financial support. Perhaps those wise founders of the NEA saw, too, the power of the arts to transform our society and express the highest values within a culture. Well, that was then and this is now; the arts no longer garner that kind of respect or funding from government sources. As well, the lofty ideals that have inspired artists for centuries are taking a backseat to the cultural driver of producing marketable creative commodities. Be that as it may, individual artists’ expressions still do have the power to shake up our inner worlds, promote self-reflection and prompt greater understanding of and a deeper connectedness to all of the planet’s communities. This idea that the arts-visual, performing, and literary expressions can and do offer glimpses into the sublime, is evidenced in the many, many paintings created throughout time and across cultures that portray spiritual leaders and significant religious events. My grandmother, for the last 50 years of her life, had hanging on her rural Wisconsin wall a reproduction of a painting depicting Jesus encircled by rays of heavenly light, praying in the Garden at Gethsemane on the eve of his surrender. Those radiating columns of visual grace that bathed the leader of Christianity represented for my grandmother the noble values to which she aspired and all human beings are called. This depiction of Jesus encouraged her to transcend her daily earthbound cares and to explore the largeness of all life.

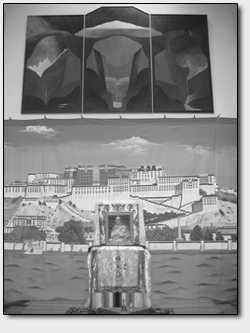

Last week I was reminded, in a most powerful way, just how intensely art can transform and shift perceptions. Upon walking into the main hall at Fort Lewis College’s Center for Southwest Studies to view the exhibit, “Circle of the Spirit: Navajo and Tibetan Wisdom for Living,” my eyes were instantaneously filled with tears as I viewed a combination of large-scale artworks placed on the north gallery wall. Permanently mounted high up, “The Garden in Winter” is a triptych painting by Stanton Englehart. Below it hung a painting on fabric of the Potola Palace in Tibet, a monastery and the traditional residence of all the dalai lamas. A moment of deep calm, then tittering delight washed over me, wiping away my preoccupations of that day, as I absorbed the restful blues of Englehart’s painting of nature-made cathedrals, the deep canyon architecture with its hints of secret water falling. Having seen this painting before, I was not prepared to be so stirred by this viewing, as it hovered commandingly above a realistically painted depiction of the glowing white palace, whose repeating rhythmical rows of windows spanning the length of the canvas, offered a soothing affect. Why is it, I asked myself, that this pairing of images could provoke such an unexpected response in me? Intellectually, I can answer that question. Both paintings are comprised of visual elements intended to create specific emotional effects; the color blue, horizontal lines and rhythmic patterns can all bring about feelings of restfulness. Both paintings portray sacred places and both artworks speak to the temporary nature of human existence; the eons of geological forces that conspired to create the canyon walls of Englehart’s vision remind us of the temporary nature of life, and the Potola Palace, the spiritual seat of Tibetan culture, houses the primary Buddhist teaching of the impermanence of all things. Still, these thoughts were not part of my visceral response to the artworks; this analysis came after the fact. I believe there was mystery at work and things we do not and cannot understand because they exist in a realm beyond the thinking mind. I believe that real art can describe the ineffable and transport us to a mysterious place that is both personal and universal. Albert Einstein said, “The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the source of all true art and all science. He to whom this emotion is a stranger, who can no longer pause to wonder and stand rapt in awe, is as good as dead: His eyes are closed.” Perhaps Einstein employed his future vision when he formed these words, for today in therapeutic settings and in many artists’ studios, the creative process is used as a tool to awaken parts of the psyche that have been stilled. To be sure that I am not just blowing hot art air on the topic, I consulted a few authoritative sources. Leslie Swanson, a certified expressive arts therapist, believes that the arts aid in our journeys to becoming fully human. “The arts speak in the language of the soul, which is a very powerful language. In his work, Carl Jung used the mandala, or circle, as a healing image … it is the root image of wholeness or integration.” Mary Mellot, once-Durango artist and trained art therapist added, “Sometimes the risks we see taken on paper or canvas or any medium for that matter, can in some ways generalize into our life through theme, color, shapes, etc. Making art as well as viewing art can stimulate the emotions on very deep and healing levels.” Please, don’t just take our words as truth; go really look at some art and feel for yourself the wonder and rapture that true art can arouse. •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel