|

|

||

|

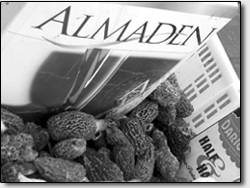

Going deep with Black Dog and the Frenchman by Chef Boy Ari Where the %$@# is the Frenchman?” growled Black Dog, pacing in front of his half-built mushroom dryer. Last news we had, the Frenchman was near Watson Lake, Yukon. When the Frenchman drops off radar, it’s usually because he’s armpit-deep in morels. The Frenchman’s absence was doubly disturbing to Black Dog, because we weren’t. Our mushroom-picking team had hit the doldrums. At the start, spirits were high, and it looked like a lucrative season was upon us. But we were not alone along Alaska’s charred Taylor Highway, and most of the burnt ground within walking distance of the road had been picked over. The buyers were getting antsy, too. Morels were trickling in, but the floodgates had not opened. “Trickle crops don’t pop,” said one buyer, gloomily, as he underpaid me for my day’s harvest. I later learned he got busted for rigging his scales. On the way back to camp I saw the red Chevy van. Every time I see that van, I feel a sense of awe. While other pickers try to hide their rigs in discrete little pull-outs and gravel pits, the red van pulls onto the shoulder in a brazen cloud, and there it sits for all to see. One time I saw it parked right next to a side road where the driver could have hidden it, if he’d cared to be discrete. Back in camp, Black Dog’s pickers bicker over who pays for what, who contributes more to the group, who does the dishes, who has to stay in camp to keep watch, etc. As the days go by and the money faucet remains closed, the group begins to digest itself like a starving animal. Black Dog, meanwhile, frets about keeping the patient alive. He wants to buy and dry thousands of pounds. That’s where the Frenchman comes in. The Frenchman can clean a patch faster than a herd of locusts. He’s got the innate knack, says Black Dog, to absorb topography, forest type, burn severity (morels pop the year following a fire) and a host of other clues, and to think like a mushroom. “When you and me go out into the woods,” said Black Dog, his eyes a thousand miles deep, “we are doing algebra to figure out where the mushrooms are. But the Frenchman … he’s doing calculus.” That night I dropped in on my buddy Baker’s camp. He and two picking partners were stumbling around, giddy and exhausted. “We got our butts whooped today,” he said, staggering to keep his knees above his feet. “Did you find any?” I asked. Baker pointed to 20 crates, nearly 200 pounds, with a market value of $1,500. “We went so far, dude,” he said. “We paid the price. There is no way I’m going back there.” In Baker’s pan, morels and onions simmered in oil; pasta cooked on the other Coleman burner. Three

times, the mushrooms and onions almost burned, three times Baker stirred them just in time. They invited me to stay for dinner. “I’ve got some butter,” I offered, “and half & half.” “I’ve got some red wine,” said Baker. “Whaddya say we go with a red wine cream sauce?” I looked at Baker like he was crazy. After his day, he did look a little crazed. But really, red wine and cream? “Your camp, your mushrooms, your call,” I said, skeptical. “But I’ve never heard of red wine and cream.” From a seated position, Baker told me to go for it. I can’t tell you the exact proportions of the wine, cream and butter, but what happened tasted like morels cooked in blood. Rich and earthy and hard to believe there was no flesh in the pan, but it was true. Just then, the red van drove by. I watched in silence. Baker pointed. “There goes the José Team,” he said. “Who?” I asked. “A crew of Mexican pickers,” he said. “They’ve been picking about a thousand pounds a day. They go deep, really deep, past the easy stuff, farther than anyone else. They make two trips a day.” Back at camp I reported the news. Kerry, the eternal optimist, pounded his fist into his palm. “Well then,” he said. “We can be like the Mexicans, too.” We looked at him over our beers. Those of us who have gone deep know what’s there. Burned trees called widowmakers, waiting for the slightest excuse to fall. Muskeg bogs full of round tufts of sod called bowling balls, ready to roll and take your ankle with them as they send you into the muck. Impenetrable thickets grab through your clothes as you clamber over downed trees. When you go deep, you come home covered head-to-toe in ashes, scratches and blood. Even the mosquitoes are afraid of you. Or maybe you just don’t feel them anymore. That was me the next day, when I stumbled into camp in the soft light of 1 in the morning to see that the Frenchman’s truck had pulled in. •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel