|

|

||

|

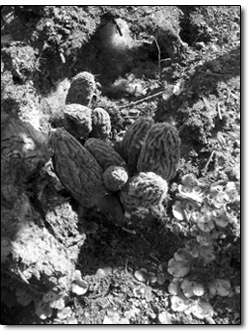

The great Alaskan mold rush by Chef Boy Ari I’m standing on a charred piece of Alaskan forest with a knife in my hand, trying to look as clueless as possible. My ears focus on the sound of a rig slowing down on the road, 50 feet away. The interloper pulls over and stares, shamelessly. My five-gallon bucket, full of morels, is stashed behind a tree. I try to look like I’ve lost my car keys. More precisely, I try to look like I’m looking, in vain, for mushrooms. Meanwhile, behind my blank stare I’m making mental notes: “A vein over there in that burned-out root system; a cluster under that cottonwood; major honker underneath that log.” As soon as the prying eye drives away, I’m on my knees, picking up where I left off. If anyone asks me if I’m finding any morels, I say “no.” If they ask me where I’ve been finding them, I might show them the patch I just cleaned out. And if they get that much real information, they are lucky. Anyone foolish enough to ask a morel plucker where he got ’em is foolish enough to believe the answer. Morels appear in great abundance a year after forest fires. At least, they’re supposed to. Sometimes they’re not where they’re supposed to be. Sometimes they’re where they’re not supposed to be. Ultimately, morels are like elk: they’re where you find them. And if you find them, you have three basic options: cook and eat them; dry them for later; or sell them. It’s the latter option, motivated by a hot market for the little fungi – $5 to $10 per pound in the field, currently – that keeps the competition stiff and the trade secrets well kept. The history of Alaska is a litany of booms. First it was furs. Then the gold rush. Then oil. And fish, of course. Today, it’s fungus. Over the hill, somewhere, my dad is picking. He came up with me to get in on the Great Alaskan Morel Rush, and today is his 72nd birthday. Wondering where he is, hoping he isn’t bear bait, I blow my whistle. He answers into his walkie-talkie. My walkie-talkie is in the car, along with the bear spray and everything else I left in my haste to pounce on this juicy piece of roadside habitat. Luckily, dad has a big, booming voice, and it carries over the hill as he speaks into his walkie-talkie. At the end of the day, we drive to a pull-out where a mushroom buyer is paying $7 per pound.

A Swiss radio lady is there, doing a story for the listeners at home about where their morels come from. Europeans eat a lot of morels, and the listeners want to hear what life’s like in the fungus fields. Swiss radio lady doesn’t know it, but Chef Boy Ari is interviewing her at the same time. “How do you guys cook morels in Europe?” I ask. “Veeth pasta und cream,” she says, telling me nothing of value. “Veeth meat.” Meanwhile, her friend Sveta, a Russian-born anthropologist with dreadlocks, is waiting her turn to interrogate me. Sveta is studying the culture of mushroom pickers. A pickup pulls slowly toward the mushroom buyer’s van. The buyer, a squirrelly guy from Coos Bay, Ore., whom I haven’t yet decided if I trust, speaks to the driver in Cambodian. The truck idles while the buyer addresses the women: “They won’t sell here unless you guys get your cameras and microphones and leave.” The women comply. After the Cambodians dump hundreds of pounds of mushrooms into crates, it’s my turn at the scale. The fruits of my day’s labor barely fill a crate. “Ten pounds,” the buyer says, handing me $70. I stand there fuming as the buyer yaps with the Cambodians, probably saying, “When stupid white boy leave, I give you good deal.” I’m sure that my mushrooms weigh more than 10 pounds, so I grab a stick of butter from my cooler and hand it to the buyer. “Could you weigh this, please?” He takes the butter, regarding me coldly, and places it on the scale. It reads 0.26 pounds – more than its actual weight! This far from the equator, the buyer explains, scales weigh a bit heavy. Hmmph. Obviously, I can think of a better way to use that butter and those morels. That night we sat by the campfire under the midnight sun, waving at mosquitoes while I melted that butter in a pan with sherry, onions, garlic and half a cube of chicken stock. I seasoned the pan with garlic salt and lemon pepper and added an enormous handful of morels – a quantity only a picker could afford. When everything was well cooked, I stirred in some St. Andre triple-cream cheese. We served the delicacy on crackers, toasting my dad’s birthday, amidst decadent sighs, and washed it down with Beaujolais in paper cups. Tomorrow, we promised ourselves, we would strike it rich. • Next week: Black Dog and the Frenchman arrive at camp.

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel