|

|

||

|

Smelter's legacy prompts concern Some believe contaminants pose a health threat SideStory: Exceeding regualtory levels: Smelter site has yet to make the grade

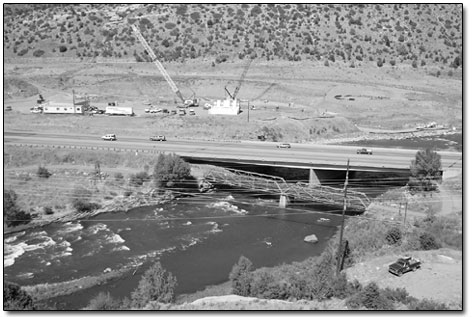

by Will Sands After 12 years of silence, the smokestacks at Durango’s smelter fired up again in 1942. For the next 21 years, the building on the banks of the Animas River and just southwest of downtown produced uranium oxide. The by-product was more than 1.2 million cubic yards of sandy tailings containing radioactive materials and other hazardous heavy metals. The U.S. Department of Energy eventually recognized the waste’s health hazards and in 1986 undertook a major clean-up of the former mill site, the current Durango Dog Park, and the mill’s old raffinate ponds, located approximately where the Animas-La Plata Project pumping plant is being excavated. The raffinate ponds were used to settle contaminated sediment and found to be one of the contaminated spots in the clean-up. The effort was completed in 1991, and the waste was transported to a sealed containment cell 1.5 miles southwest of Durango in Ridges Basin, alongside the future location of the A-LP reservoir, Lake Nighthorse. The sites were cleaned to Environmental Protection Agency standards, and the effort was hailed as a success. However, the DOE and the San Juan Basin Health Department have both acknowledged that the clean-up was not perfect. Residual contaminant's remain at the mill site, the raffinate ponds, along Smelter Mountain, in the groundwater and through the Animas River. “Some residual contamination was left in place in two regions along the banks of the Animas River, in unreachable areas of windblown contamination on the slope of Smelter Mountain, and in soils in the raffinate ponds area,” stated a DOE report. Some now fear that the residual contamination may be more significant than widely believed. “The Department of Energy released a report (see sidebar) saying it could be 100 years before we reach compliance levels,” said Travis Stills, local attorney and environmental activist. “We need assurances now that these heavy metals issues are under control. I don’t see that anything is being done.” Michael Black, of Taxpayers for the Animas River, concurred that there are still contamination issues related to the old Smelter. However, Black goes back well beyond the clean-up to a time when tailings were being dumped directly into the Animas River. “From 1942 until 1957, the Smelter dumped all of its contaminant's directly into the river,” he said. “Fifteen tons of dissolved sands were released into the river each day, and most of that settled out within 2 miles of the discharge point at Lightner Creek.” Citing the material’s high half life of 16,000 years, Black suggested that the contaminant's are still in the Animas and not far from the original discharge and the old Smelter site. “It’s a fact that material is in there somewhere,” he said. “Where it went nobody knows. I’d suspect it’s something that people really don’t want to know. But my thinking is that uranium is a heavy material, and it didn’t go far. It probably settled out first and settled out immediately.” Black concluded, “My assumption is that the Animas River from Lightner Creek down is still contaminated.” This decades-old issue has become timely courtesy of the Animas-La Plata project, the ambitious pumping plant and reservoir being built just southwest of downtown Durango. The Bureau of Reclamation recently completed excavation of the pumping plant, a major earthwork project that was done beneath much of the old raffinate ponds. “Here it looks like the uranium processing and A-LP boondoggles are converging,” Stills said. “Unfortunately, I’m not aware of anyone who is watchdogging these folks to make sure they are doing a good job.” Ken Beck, A-LP Team Project Leader, countered that the Bureau heeded the fine print of its Environmental Impact Statement and monitored radiation levels throughout the pumping plant’s excavation. “Anytime we’re out there, there’s a problem,” he said. “But the biggest threat is when we’re excavating. So when we excavated the pumping plant, we had someone on site with a Geiger counter the whole time, and they never registered any reading higher than the background radiation.” Beck explained that the excavated material has all sat at the building site, and monitoring will resume after the plant is built and the material begins going back in the ground. Based on the monitoring, Beck concluded that the clean-up of the raffinate ponds area was successful, saying, “It looks like the folks with the clean-up did a pretty good job.” Regardless, Stills and Black have unresolved concerns about the combination of contaminant's and the reservoir. “There’s a very serious potential for contamination in the reservoir in Ridges Basin and in the pumping plant itself,” Stills said. “Unfortunately, we’re putting our trust in what I consider to be an untrustworthy agency.” Stills explained that the containment unit holding the 1.2 million cubic yards of radioactive material will be located alongside Lake Nighthorse, and that it is not a question of if, but when, the unit will fail. “That disposal site is on the banks of a proposed reservoir,” he said. “It is going to seep, and it’s going to contaminate the reservoir. It’s that simple. This is the stuff that cartoons are made of, and it’s happening right outside our doors.” In addition, Black noted that the water pumped from the Animas River into the reservoir will contain some contaminant's. Over time, the addition of sediment will concentrate the heavy metals and radioactive materials, causing Black to comment, “Will putting something into a reservoir concentrate contaminant's? Absolutely.” With these two factors in mind, Stills said that he is especially disappointed in the City of Durango’s recent purchase on an option to buy municipal drinking water from Lake Nighthorse. “It was unconscionable for Durango to buy an option on the project without a full and completed federal program that eliminates the radioactive and hazardous threats on the Animas and in Ridges Basin,” he said. Health hazards at the Smelter site, the containment cell and in the Animas River all need to be more fully investigated, according to Black. He concluded that it is shocking how little information there is on the real contamination of the Animas River and the old Smelter site, saying, “Personally, I find the whole thing extremely disturbing, and yet, nobody seems to know anything.” •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel