|

|

||||

|

Art as protest

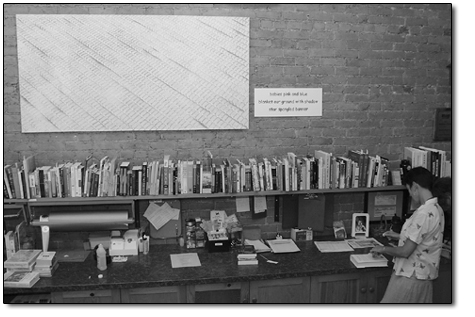

by Jules Masterjohn Artists have been making pictures of the sacred and the profane since the tip of a stick drew lines in the sand. In the realm of the sacred, there exist perhaps thousands of images portraying scenes from the Bible, sculptures of Hindu and Buddhist deities, and pre-Columbian gods, to name just a few. Expressions of the profane, as I define it here, are depictions of events and situations that violate our humanity and dignity… such as war. Depicting the realities of war has been a compelling topic for artists. In 1814, Spanish artist Francisco de Goya painted “Execution of the Third of May, 1808,” which pictures a firing squad lined up, taking aim at a Spanish citizen who stands near a pile of dead bodies. Goya’s painting documents the heinous actions of the occupying forces in Madrid on one evening during Napoleon’s military campaign. A grim and truthful portrayal, this history painting is but one of many that record the horrors of war. Another Spaniard, Pablo Picasso created a more contemporary anti-war painting, “Guernica.” Exploding with violence, its monochromatic composition emphasizes the dramatic: a chaotic street scene; a dead child held by a grief-stricken mother; a horse frozen in a horrific heavenward scream. His painting captures a hellish moment in Guernica, Spain, during a three-hour raid by German bombers in a test of their aerial firepower that killed more than 1,600 Spanish civilians. Though Picasso did not personally witness the devastation, newspapers were filled with photographs and eyewitness accounts, which became the inspiration for his painting. Commissioned by the Spanish government for display in the Spanish Pavilion during the 1937 World’s Fair, “Guernica” has since traveled the world and currently is at home in Madrid. Located around the world are numerous life-size reproductions on public display, such as the tapestry copy at the entrance to the Security Council chamber at the United Nations. Purchased by the estate of Nelson Rockefeller and placed there in 1985 as a show of solidarity with the mission of the U.N., “Guernica” was covered up by a baby-blue curtain while representatives from the current administration made their televised imperative for the invasion of Iraq. Apparently “children and animals shouting with horror and showing the suffering of the bombings” was not an appropriate backdrop for this press conference, stated a diplomat. Before and since Picasso, artists the world over have created art about war. The occupation of Iraq inspired one of Latin America’s most famous artists, Fernando Botero, to produce 50 paintings depicting the torture of prisoners at the Abu Ghraib prison. An exhibit of Botero’s work, which includes these paintings, opened in Rome last month to a huge crowd. Locally, a piece of art that honors the U.S. casualties from the Iraqi invasion and occupation, hangs on the wall of Maria’s Book Shop in downtown Durango, where it will show for the next few weeks. Produced by Ricardo Moreno, this 3-by-6-foot pastel drawing was plotted out with a surveyor’s eye, which is Moreno’s profession. He covered all 15 square feet of his drawing with 1,618 small grave markers, each casting long shadows on the ground, similar to aerial views of Arlington Cemetery. At the time Moreno laid out this piece, 1,618 U.S. soldiers had been killed in Iraq. By the time he finished and titled it, 1,737 had fallen. Unofficially titled, “1,618 Shadows of 1,737,” the last number can change daily to reflect the current number of U.S. war dead, which as of this writing was 1,752. The drawing is accompanied by a haiku:

babies pink and blue blanket our ground with shadows. star spangled banner. Moreno’s title and poetry bear witness to his intention that the drawing be a constant reminder to “keep these losses close to our hearts and stay conscious of the suffering that this war is causing.” Using the drawing’s visual elements to reinforce his message, he said, “I chose to use pink and blue pastel as a reminder that only a few years ago, most of these soldiers were boys and girls. The shadows in this painting remind me that only memories remain of their true potential.” Once the drawing was complete, Moreno recalled, “I was surprised to see that it reminded me, in an abstract way, of the U.S. flag.” Durango artist Karen Pittman created an artwork in 2000 using an actual American flag as the background on which other elements – a TV screen and a rewritten version of the “Star-Spangled Banner” lyrics – are arranged. If the proposed Flag Desecration Amendment is passed by Congress, artworks incorporating the flag, like Pittman’s mixed-media piece, “Oh, Say,” could get their creators incarcerated. Another of Pittman’s pieces, “God, Good, Goods,” expresses none of the atrocities of war found in more graphic works like “Guernica,” but instead takes an intellectual approach, triangulating the conditions that bring about war. Pittman juxtaposes lyrics from “America the Beautiful,” reprints from the Stock Market report, and text from the Bible into a flag format with a pie chart replacing the starry field of the flag. Pittman explained, “A pie chart represents how we gauge our resources. I put market reports into three sections: animal, vegetable and mineral … these are the things taken from the earth to produce our stuff, our ‘goods.’” Having studied the Bible when she was younger, she remembers the first chapter, Genesis, in which it is repeated seven times, “and God saw that it was good.” Pittman didn’t start out with intentions to make a piece of protest art, she said, it just happened. “Making this piece was quite an ‘ah-ha’ process for me … we go to war in the name of God, for what we perceive as good, and to obtain the goods. Making these pieces influenced my world view. They may not have influenced anyone else’s life, but they profoundly affected me.” Moreno’s “1,618 Shadows of 1,752” will travel from Maria’s Bookshop to Animas Trading Co. and Dancing Willow Herbs during the next few months. Next week’s article will continue this focus on political art by featuring the work of local artist Maureen May. •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel