|

|

||

|

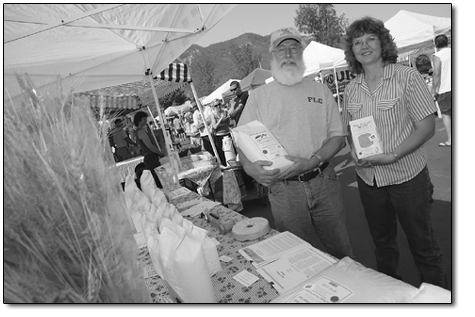

Filling the cafeteria with local food Groudbreaking Farm to School porject makes first local strides SideStory: A clearer picture of locally grown foods

by Will Sands Locally raised beef, vegetables and grains could be taking the place of fish sticks, canned peas and tater tots in La Plata County’s school cafeterias. Food grown by regional farmers will make its first move into area schools this fall, courtesy of a local outgrowth of the national Farm to School program. The effort is being hailed as positive for students, parents, growers and the community at large. Farm to School is rooted in a simple concept. Schools, the most community-driven of all institutions, should directly support local farmers and ranchers. In turn, children’s nutritional needs are better served, and they are educated about food systems and local environmental issues. It is a natural fit for Jim Dyer, whose Southwest Marketing Network is dedicated to helping small-scale Southwest agriculture operations network and market their produce. “This isn’t just a farmer wanting to make a buck,” said Dyer, who is coordinating the local Farm to School effort. “This will help the entire community.” Dyer explained the far-reaching benefits of having locally grown foods in the cafeteria, saying, “It’s a new market for local producers. It’s likely to bring more nutritious foods into La Plata County’s schools. It should increase students’ understanding and the understanding of everyone they touch about local agriculture. And it helps the community by keeping money circulating locally.” Dyer added that in established Farm to School programs elsewhere in the nation, the relationship is flourishing, saying, “In some cases, the schools become farmers best and most reliable customers. Plus, as you get more foods into schools, it engages local producers. This could be a good way to expand local food supply.” Shari Fitzgerald is a program director with the Garden Project of Southwest Colorado. The project focuses on creating educational and therapeutic gardens in the area for disadvantaged youth, older adults and low-income families and is also a natural fit with Farm to School. “Our position on Farm to School revolves around working with students of public schools,” she said. “We’ve seen that our youth are in the greatest need of receiving healthy and nutritious food. Nationally, 30 percent of youth are overweight, and diabetes and obesity are becoming major problems.” Fitzgerald also said she believes education to be one of the most valuable prongs of Farm to School. She has advocated the creation of school gardens, the addition of agricultural education into existing curriculum and in-class and experiential education on sustainable agriculture. “There’s getting the food into the cafeteria, and then there’s a second piece of this,” Fitzgerald said. “That second piece is education of students, staff and parents. You have to have both.” The perception that students crave only franchised, fast food is off-base, according to Fitzgerald. Particularly at older ages, students are requesting more whole foods and making an association between health and diet. “I know Durango High School did some surveying and found that students are saying, ‘We don’t want pizza every week and would like to see healthier food,” she said. “But you also need to have education. People aren’t always instantly receptive to organic food.” Bliss Bruen is a local resident who also has been actively involved in birthing a local Farm to School program. Beyond improving local agriculture and nutrition, Farm to School could provide a sweeping model for the rest of the state to follow, according to Bruen. “The real question we are asking is, ‘Under the best conditions, how food self-sufficient might we become in La Plata County?’” she said. While the effort is being aimed at all of La Plata County, Durango School District 9-R has seen the wisdom of Farm to School, according to spokeswoman Deb Uroda. The district has held several positive meetings with Farm to School. As a result, the Student Nutrition Services Department will be working with area farmers and ranchers to serve more locally raised produce and meat. However, don’t look for a full menu of foods grown in La Plata County. Dyer commented that Farm to School is going to start slowly and that expectations are currently realistic. “Our group decided at the first meeting that our goal was to have some local food in some local school by this fall,” he said. The rationale behind the long timeline is that the seemingly simple arrangement has many hidden complexities. Chief among the obstacles to a successful, local Farm to School program is financing. Dyer noted that school lunch is currently federally subsidized, and cafeterias are provided with very inexpensive food. “We’re all very aware of the huge constraints,” he said. “They get federal aid, and there are strings attached. They get food at rock-bottom prices, but in our view, there is no comparison in terms of quality.” Dyer and Bruen agreed that the quality of food could provide the final solution to the financing dilemma. Better food could mean more students eating school lunch and eventually an end to the district’s tight budget for food. Bruen noted that federal reimbursements are tied directly to participation levels and higher participation will mean more funding. “How do we increase their numbers?” she asked. “By marketing a dynamite local salad bar with really green lettuce and delicious tomatoes and fruits and nuts. The director of the Santa Fe Farm to School program says that they cannot keep up with the demand for sunflower sprouts.” She added that the true price of local food drops when you start examining “hidden costs” like impacts from food transportation and long-term health issues. Bruen, Dyer, Fitzgerald and the others working on the project are all hopeful that the community and school district will recognize these less obvious costs and help “jumpstart” Farm to School in La Plata County. “If we’re going to subsidize something, what better than the health of our children,” Bruen concluded. “But the school district is going to have to hear from the community. The community is going to have to come out and say that this is valuable.” •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel