|

|

||||||

|

Not just for recess anymore

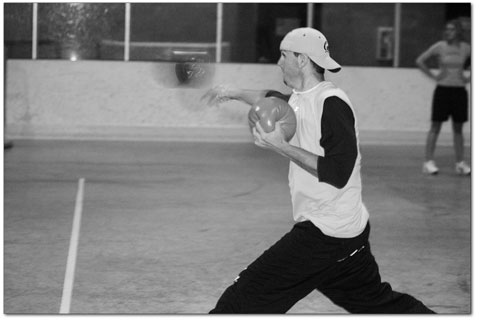

by Amy Maestas As players warmed up on the outskirts of the Chapman Hill ice rink Tuesday night, I had a familiar, chest-tightening sensation kick in. Instantly, I flashed back nearly 27 years to the newly laid asphalt on the elementary school playground. With the brilliant yellow lines painted on the jet-black surface still emblazoned in my memory, sweat beads welled on my upper lip. The images invoked childhood anxiety. It is not quite Proustian; it’s a bit more painful. We all have a story or nine about horrifying playground games. In this, I knew I was not alone. At Chapman Hill, Tammy Johnson was with me. It was her fault – all her fault – that I was there. (Oh, alright – and the fact that I was writing this story about how hot the grade-school game of dodgeball is among adults now.) But let me blame it all on Tammy Johnson. Please. For millions of schoolchildren across the country, dodgeball was a popular recess diversion, if not a regular cardio stint during a brief gym class. In my sixth-grade year, Tammy Johnson took humiliation to a new level. She wrapped her petite hands around the red rubber ball and, her back brace be damned, hucked it right at me, complete with a professional quarterback’s spin. I ducked. She missed. When I stood up, I turned to her with a frighteningly innocent “whatever-did-I-do-to-you?” face. I said nothing. She, however, did. She looked me squarely in the eyes and called me a “%&*!^#.” Never mind that I skillfully dodged her ball. Her monotone expletive stung worse than the crosshatches of that ball to my skin. How, I asked myself, could anyone think that I, of all people, was a %&*!^#? Tammy Johnson’s ugly bluntness defined dodgeball for me. So showing up at Chapman Hill to briefly play among those on a Durango Parks and Recreation league was meant to heal me. I was curious whether adults could pull off similar gym-class heroics without insulting one another with the f-word. Thankfully, they did. Player Zach Cooley remembered that during his childhood, playing dodgeball (or “bombardment,” as he called it) was sometimes difficult to endure. Kids anxiously awaited the team-picking process, only to then be lined up for a chance to get beaned. But, he says the pain wasn’t deep enough to keep him from taking on the sport as an adult. Like others, he views the childhood game as a necessary lesson on toughening your skin. Cooley also says he joined the city league for “lack of anything better to do on a Tuesday night.” The chaos of ducking players and fast-pitched balls flying willy-nilly in the air certainly makes a Tuesday evening more exciting. Among the Durango players, there was, just like childhood, a mix of intensity. Some had the concentration of spoon benders, with their eyes darting speedily to find a victim to pummel. Others laughed and mocked themselves with just the right amount of self-flagellation while limping off the court. But no matter the level of play, local dodgeballers are excited to introduce a new sport to a sports-centric town. The Ballers, a long-standing team of players that participates in every rec league sport offered, welcome the game to break up the monotony of mainstream games. “It’s something new to play instead of softball,” says Baller Ryan Patterson, who played the game during grammar school. Mostly, Patterson admits, he likes playing the game because “you get to hit people.”

Patterson says he has a fondness for the game, not chilling memories. The same goes for teammate Marianne Powell. They say that it’s about childhood nostalgia, perhaps even a trend for retro irony. Powell says she played dodgeball only in high school, where football players and other letter-seeking athletes played with forceful aggression. Still, she enjoyed it enough to revisit it in her adult life. She also touts its benefits of aerobic exercise. The fast-paced, nonstop games last two minutes each. The first team to win five games wins the match. A match often doesn’t even extend to 30 minutes. The adult version of dodgeball is somewhat different than the children’s. Adults place six balls on a center line with teams lined on opposite ends of the playing area, The teams then run to the balls, picking them up and retreating behind the line before putting the ball into play. Someone hurls the ball at someone else. If he hits a player without the ball bouncing first, that player is eliminated. If the target player catches the ball instead, the thrower is out and the catcher gets to invite an eliminated player back to the fold. The court is usually 60-by-30-feet, like a volleyball court. Instead of using the red rubber balls ubiquitous on schoolyard asphalt, adults typically play with rubber-coated foam balls. Kids aren’t quite as technical about it. In one version of the game, they form a circle, encasing a team of players inside. Players in the outside circle then throw at players in the inner circle, hoping to hit them, thereby eliminating them from the pack. In either version, the goal simply is to hit and eliminate everyone on the opposing team.Once successful, the game is over. Dodgeball’s renaissance began just more than a year ago after a Hollywood movie of the same name about a group of misfits who prevent owners of a fancy fitness center from taking over their gym. (Full disclosure: I have not seen this movie, though I am sure Tammy Johnson has.) Since the movie’s release, recreational leagues and professional teams have sprouted up throughout the country, bringing many participants back to their schoolyard days with fondness. It’s a cultural phenomenon now that Vanity Fair has dubbed it an “it sport.” The New York Times and Fortune also recently acknowledged its comeback, especially among adults of a certain age and aesthetic. Popular culture has been metastasized to include post-graduate, Ulysses-reading, trendy-glasses-wearing latte drinkers in a game that, historically, mainly schoolyard bullies enjoyed. Powell and Patterson believe that the movie is partly responsible for the game’s reappearance. They also cite the extreme version played on a cable TV game channel. Matt Morrissey, Chapman Hill manager, agrees. The city introduced the league in order to satisfy a request from residents. There was enough interest to make a go of it, he said. How often the league is offered depends on initial success. The city league started in mid-July and wraps up next week. But while grown-ups have been playing in recreation centers and even newly built dodgeball stadiums, school kids across the country have been increasingly denied the chance to partake in a game that has all the necessary elements of having a typical childhood – humiliation, emotional vulnerability and physical awkwardness. Many school districts have banned the game from being played, saying it is too violent and too damaging to a child’s self-esteem. “I think that’s a bunch of gibberish,” says Cooley. Patterson agrees, pointing out that it’s no more violent of a sport than football or other mainstream games. “But kids were tougher back in our day,” he quips. Tough as Tammy Johnson, I’d say. •

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel