|

|

||||||

|

The plight of the wild horse Mustangs face uncertain future in face of new legislation SideStory: A chance to bring a mustang home

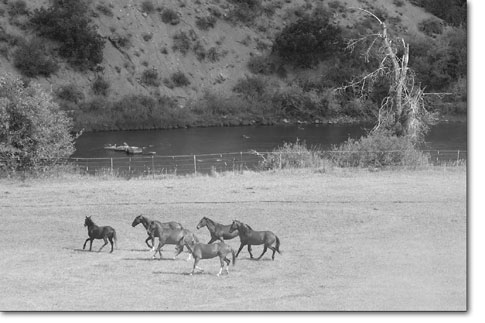

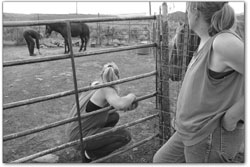

by Missy Votel Early last April, Alicia James brought home a wild horse from the Bureau of Land Management’s wild horse and burro holding facility in Cañon City. The horse was among a group of seven that James, operator of the nonprofit Windflyers Mustang Sanctuary south of Durango, had looked at. Although she would have liked to have taken them all, she said finances and lack of space at her 15 acres of leased land south of Durango prevented her from doing so. A week later, a former rodeo clown claiming to be a preacher from Oklahoma visited the Cañon City facility and bought up the remaining six horses from the group at $50 a head. He told BLM officials he planned to train the horses for a church youth program. But three days later, the horses were dead, sold to a Belgian-owned slaughter house in Illinois for a tidy profit of $1,500. The news, in addition to making national headlines, deeply saddened James, who, along with her mother, Debbie Gates, has acquired eight wild horses over the last two years. “It hurt,” said James from her ranch off La Posta Road. “We had seen those horses and wanted to bring them all home, but we could only take one. It really hit home.” Change in policy The BLM periodically rounds up wild horses on Western public lands in order to keep herd numbers in check and better manage the range. Two large herds of wild horses are located in the Four Corners region, the Jicarilla herd near Bloomfield, N.M., and the Disappointment Valley herd, north of Dove Creek. Many of the younger, more trainable horses find new homes through the agency’s adoption program. The older, less adoptable ones end up at holding facilities like the one in Cañon City, where they eventually are adopted or sold as-is to private citizens, trained by Cañon City inmates and then sold at auction, or sent to federal sanctuaries where they can live out their years in a free, but slightly more restrictive setting. Up until this year, the horses were protected under the 1971 Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act, which protected these vestiges of the American West from would-be commercial exploitation. The act came about as a result of public outcry over the drastic reduction in the herds’ numbers due to the encroachment of man and brutal commercial harvesting at the hands of “mustangers.” Although disdained in the United States, horse meat is widely used for human consumption in Asia and Europe, thus there was money to be made off the capture and sale of wild horses. Under the act, titles to horses were not turned over until a year after adoption or sale. The lag allowed BLM officials to ensure the animals were being properly cared for and also deterred the sale of horses commercially, since the cost of a years’ feeding and care canceled out any potential resale profits. However, in December 2004, a last-minute rider slipped into the 2005 federal appropriations bill by a Montana senator removed this protection. Under the new law, forwarded by Sen. Conrad Burns, R-Mont., wild horses over the age of 10 or ones that had been unsuccessfully offered for adoption three times were to be sold outright “without limitation.” Since then, the BLM has sold about 1,000 horses. Forty-one have been slaughtered, including the six from Cañon City and another 35 that were originally sold to the Rosebud Sioux Indian Tribe in South Dakota for $1 a piece and later traded to a horse broker who sold them to a slaughter house. The situation came to a head in late April when the BLM learned that another 52 of the Sioux horses had a date at the slaughter house. The agency intervened, and with the help of Ford Motor Co., the horses were bought back for $20,000 and placed in a sanctuary. The agency also temporarily suspended sales of horses in holding facilities to reassess the program. Soon after, two bills were introduced into Congress, one that would restore protection of wild burros and horses, and one that would ban horse slaughter in the United States all together. Although neither bill has gained much ground, BLM officials say they have gone ahead and reinstated sales of wild horse sales with new safeguards in place.

“We changed the bill of sale and put restrictions on it,” said Fran Ackley, Wild Horse and Burro program leader for Colorado who works out of the Cañon City facility. Under the new restrictions, buyers must sign a bill of sale agreeing not to sell or transfer ownership of horses to anyone who intends to process them for commercial products. Anyone making false statements could face criminal penalties. Ackley said so far, the new rules seem to be working. “Things have slowed way, way down,” he said of sales, adding that the agency also has become more stringent with its pre-sale interviews. “Some people we took for their word, and they weren’t very forthcoming with the truth,” he said. “Now, we go through the interviews and can refuse anyone.” However, he said until new legislation is passed, the agency’s hands are tied. “Under the wording of the bill, we have to sell these horses,” he said. The purpose of the bill, according to Sen. Burns, is to reduce the costs of capturing and caring for such animals, which now totals close to $30 million a year. The savings, plus proceeds from the sales, would go toward promoting a more successful adoption program, he contends. Born to be wild Currently, there are 22,500 horses in a dozen holding facilities throughout the country. The Cañon City facility has about 625 horses at a cost of $3.25 per day per head, Ackley said. But, he notes that costs at his facility are lower due to the abundance of cheap labor – inmates from the federal prison there. Since horses that do not sell are eventually brought to one of nine sanctuaries, where care over the course of their lifetimes can run upwards of $10,000, it behooves the agency to train the horses to be sold at auction. Ackley said there are two inmate horse-training programs, one for saddle horses and one for harness-led horses. “One of our top saddle horses just went for $5,800 at auction,” he said. The proceeds from such sales go back into the wild horse program, he said. Unfortunately, Ackley said such stories are the exception rather than the rule. Most of the horses at his facility are older than 10, making them unsuitable for the training programs and undesirable for people looking for a horse to train themselves. “A majority have been out on the range for so long that they are not going to be trainable without a whole lot of work and experience,” he said. “And once you do train them, it’s questionable whether you’ll ever have a trustworthy horse.” But the untrainable ones are just fine with James, who would prefer to keep her horses wild anyway. All eight of her horses have been rescued either from holding facilities or people who adopted them but could no longer care for them. Another former Cañon City horse, by way of Parker, Colo., is scheduled to arrive at Windflyers on Sunday. “When we get the horses, they’re really scared, so we try to leave them as wild as possible,” she said. With the sanctuary almost at capacity, James said she is planning to talk with the Southern Ute Tribe to lease another 30 to 40 acres adjacent to her property, which will allow her to bring in even more rescues. James, who relies on private donations and her own pocket to operate, also envisions one day opening an education center for the public. “The goal is to show them what horses have done for us over the centuries and in helping to settle the West,” she said. “We wouldn’t be who we are today without them.”

|

In this week's issue...

- December 18, 2025

- Let it snow

Although ski areas across the West have taken a hit, there’s still hope

- December 18, 2025

- Look, but don't take

Lessons in pottery theft – and remorse – from SW Colorado

- December 11, 2025

- Big plans

Whole Foods, 270 apartments could be coming to Durango Mall parcel