|

‘Folding Paper Cranes’ a haunting memoir of making peace from ground zero

|

|

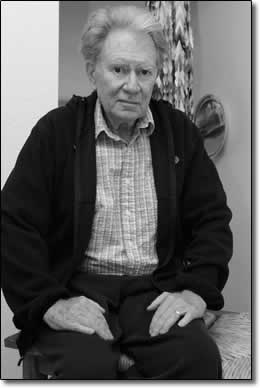

Leonard Bird relaxes at his home west of Durango onMonday morning./Photo by Todd Newcomer.

|

by Shawna Bethell

Folding Paper Cranes: An Atomic Memoir, by Leonard Bird, University of Utah Press, 150 pages.

When you finish reading Folding Paper Cranes: An Atomic Memoir, by Leonard "Red" Bird, you

don't just put it down and walk away. You carry the story with you as though it was your own journey, so exceptional

is the manner in which Bird takes his reader with him.

The journey is that of an atomic veteran, an "expendable pawn" as Bird states, who witnessed the government's 1957

test detonation of Shot Hood, a device six times the size of Little Boy, the atomic bomb that was detonated over

Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945. From a 5-foot deep trench on Yucca Flat, on the Nevada Test Site, and 4,000 yards from

ground zero, Sgt. Bird and his buddies, Washington and Begay, were ordered to face the firebomb that rose 60,000 feet

in the air and rained down poison and fire across the expanse of a devastated American desert.

It is this memory, juxtaposed with that of his visit to Hiroshima three years before, that begins the memoir. During

his 1954 visit to the International Park for World Peace, Bird was an 18-year-old Marine more interested in a

weekend's leave of carousing than taking a meaningful pilgrimage. He could not comprehend why a city annihilated had

concentrated its efforts in building a park instead of houses and industry. The irony is that after his experience at

Yucca Flat, Bird realized he was inextricably bound to the survivors of the Hiroshima blast and years later, would

come to understand their vision.

Shot Hood left Bird with more than nightmares, as his body took on the poison of the radioactive fallout. The third

chapter of the memoir, entitled "Collateral Damage," explores the period of Bird's life when he is diagnosed with

multiple myeloma, exactly 45 years to the day of his initial exposure. A slow on-set bone-blood cancer, multiple

myeloma is directly linked to radiation poisoning. But Bird spends few pages looking back at his physical illness.

"I didn't want the book to be primarily about me," said Bird, "I didn't want it to be self-pathetic. I wanted it to

be about the places involved."

"I didn't want the book to be primarily about me," said Bird, "I didn't want it to be self-pathetic. I wanted it to

be about the places involved."

Indeed, regardless of the horrific darkness of nuclear war and the devastation that he saw, Bird creates a memoir of

hope. It was not the cancer that inspired Bird to write Cranes, but it was the illness that gave impetus to its

completion. It was 1993 and his third and final visit to Hiroshima that inspired the hope that Bird wanted to find.

The second section of the book, "The Courage to Hope," recounts this experience and the Hibakusha (atomic-bomb

survivors) he met there.

"I badly needed, finally, to weave together the disparate threads of my history with Hiroshima and

Yucca Flat," writes Bird.

His second trip to the peace park, in 1981, had done little to heal his fear about the state of our war-absorbed

world. But during his final pilgrimage Bird met Mr. Tanaka, whose wife and daughter perished in the devastation of

1945. Through conversations with Tanaka, Bird illustrates the emotional process of regaining a faith in humanity. It

is here that Bird's prose becomes most powerful as he describes his own despair, the distinguished integrity of Mr.

Tanaka and the effervescent youth of Meiko, a young girl who represents the future of our world's children.

In this final installation, the reader walks with Bird through the International Park for World Peace on the day of

the Flower Festival and ends with his visit to the Children's Memorial. This memorial honors Sadako Sasaki, the

14-year-old leukemia victim who attempted to fold 1,000 paper cranes before her death. According to tradition, this

would bring good luck. By the time of her death in 1955, she had completed 644 cranes. Her classmates then began

folding the remaining cranes and continued to do so. The memorial is draped with colorful origami cranes continually

replaced by visitors who carry on the tradition. It is this story that lends its name to the book. The book, says

Bird, is his crane.

Though Bird had said that his book does criticize the American government, it is not anger that you see in his poetry

and prose. It is instead a dedication to "the underlying, essential and problematic premise that we can learn and

build a more enlightened world."

|