|

Manna director honored for touching the community

|

|

Kim Workman, director of the Manna Soup Kitchen, jokes with volunteers as she enters the kitchen Tuesday afternoon. Workman, who has been with Manna for 3½ years, was honored as Nonprofit Director of the Year by Operation Healthy Communities last week./Photo by Todd Newcomer.

|

by Missy Votel

The aptness of Kim Workman's name is lost on no one, least of all her peers. Last week,

Workman, the executive director of the Manna Soup Kitchen, was named Nonprofit Director of the Year by Operation

Health Communities. Workman was selected from a field of nominees by members of other area nonprofit agencies as part

of Colorado Nonprofit Week.

Workman, who has served as the soup kitchen's director since September 2001, said the award, which she admits to

being the first she's ever won, came as a complete - and pleasant - surprise.

"I wasn't expecting it at all. I was tickled pink," said the former Arkansasian in her distinct southern drawl. But

don't let the disarming accent fool you. Workman rules her domain with an iron fist and the swagger of a drill

sargeant.

"There are tons of rules," she said, which run the gamut from no drinking ("if they come in intoxicated, I give 'em a

sack lunch") to no backpacks ("because I know what's in 'em") to no muddy shoes ("your mother doesn't live here.")

Nevertheless, it's obvious that behind the iron fist lies a heart of gold.

"It's very important that this place stay safe," she said. "I yell and scream and holler at them, but they know I

love them."

And, for the most part, Workman says the rules are respected, with only one person ever being banned for bad

behavior. "But he can come back now," she added.

In 3˝ years, Workman has taken the soup kitchen, which was briefly homeless itself, from serving sandwiches and soup

out of the back of her pickup to a squeaky clean, new facility with showers, laundry, a vegetable garden and an

industrial kitchen.

"It was an absolute mess," she said of the first year and a half, when meals were prepared in the First Baptist

Church and served in the Sacred Heart Catholic Church parking lot. "But it was one of those things that if God had

put me in a building from the start, I never would have gotten out there."

Perhaps the most notable part of Workman's journey is the fact that she has a degree in animal husbandry and a

background in corporate America, working for the Cargill Corp. for seven years. Upon moving to Durango several years

ago, Workman said she held down various, unfulfilling jobs until she was heavily recruited for the Manna director job

by a board member/fellow churchgoer.

"If you knew me then, I had nothing to do with soup kitchens or homelessness," she said. Nevertheless, she finally

accepted the job. "The only thing I can attribute it to is, my mom said when I was little that I made enough gravy to

feed an army," she said. "I've got hospitality in my heart."

Last year, this hospitality, along with Workman's staff of two and more than 200 volunteers, fed more than 31,000

people. On an average day, Manna, which turns 20 this year, serves about 90 people, with numbers peaking in July at

around 150. In addition to weekday lunches, Manna has added a Saturday morning breakfast and is hoping to add a

Sunday "brunch" and a monthly family-style dinner. Mondays, Thursdays and Fridays are "shopping days," when excess

food is put out on the tables in grocery bags for the taking.

"We're just doing our thing," she said. "It's a challenge every day, but it's a fulfilling one."

According to Laura Lewis, executive director of Operation Health Communities, the award, now in its third year, goes

to someone who not only exhibits success at his or her work but fosters other nonprofits as well.

|

|

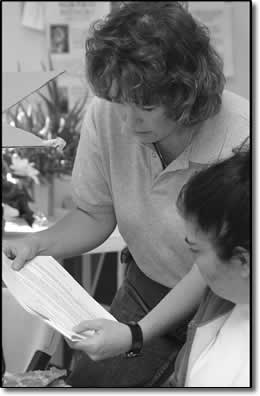

Workman helps Manuelita Martinez fill out a job application during lunch Tuesday. Workman often serves as a referral for her clients looking for work./Photo by Todd Newcomer.

|

According to Laura Lewis, executive director of Operation Health Communities, the award, now in its third year, goes

to someone who not only exhibits success at his or her work but fosters other nonprofits as well.

"We look at somebody who mentors other nonprofits and is willing to share their experience and their facilities," she

said, "somebody who touches different parts of the community."

She added that Workman's dedication was paramount in her being chosen.

"She's the type, I know, who never leaves work," said Lewis. "Even when she's at home, she's got a donated ham in her

refrigerator."

In addition to working with several local churches and civic groups, Manna is a referral agency for the Durango Food

Bank, helps out the Silverton Food Bank and collaborates with Fort Lewis College students on the vegetable garden,

Workman said.

"We cooperate with as many other groups as we can," she said.

But the soup kitchen also touches the community in more profound ways, she said. Most volunteers come on a regular

basis, finding they "get more out of it than they give."

"They get to love the unlovely, and that does something to your heart," she said.

But volunteers are not the only ones who Workman sees undergo a change of heart. Just this week, she answered a call

from a prospective employer seeking a reference for one of Workman's regulars, a recovering alcoholic. She is frank

and straightforward with the employer over the man's past, but notes she believes he has turned a corner and is eager

to prove it to the world - if only given a chance. And it is this philosophy Workman uses in her everyday approach

whether it's giving a job reference or merely handing a broom to one of her clients needing to pay off a $2 shower.

"It's an esteem issue," she said. "You hand them a broom and tell them to sweep, and they realize, 'Hey I can work'

and it builds from there," she said.

In fact, it is this sort of self-sustainability that Workman envisions for the future of the soup kitchen. She would

like to use produce from the garden for either a barbecue sauce or pickles, which would be sold to benefit the soup

kitchen.

"If we did that, I could hire a few of my folks and not only make money for the soup kitchen but for my people and

then I could retire," she adds with her genuine, southern laugh.

Of course, Workman knows that day is a long ways off.

"At first, people said, 'Oh no, don't build a soup kitchen because then they will come.' But then people realized

they were already here," Workman said. "We're always going to have hungry people, and we're always going to have

alcohol. So we'll always have the problems they bring."

|