|

A look at the dynamics of drawing

|

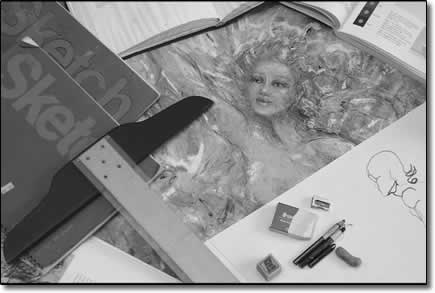

| A collection of drawing materials make up their own artistic still life arrangement./Photo by Todd Newcomer |

Recently in an art appreciation class that I teach at the local community college, I wanted to give the students a firsthand experience that would cultivate a deeper understanding of artists and their art. By using various drawing materials and following cursory instruction in a few technical areas, the assignment was to draw a still life arrangement, consisting of a large exercise ball, a floor plant, a chair, a box and a skull. As soon as the students began their foray into drawing a contour line around the shapes in the still life arrangement, I heard moans uttered under the frustrated breath of more than one student. These sounds of discouragement are not unfamiliar to me I have heard many people during my art-centered life disappointedly confess, "I can't draw a straight line."

As I listened to the mutters of discomfort, I offered to the students that, like learning to play an instrument, it was necessary to practice to develop a skill. Drawing is no different, in that anyone can learn to draw a realistic chair with a skull resting upon it. As I watched these students courageously attempting to draw what they saw, my belief was reinforced that there is a well-bred myth about art-making in our culture. There appears to be an expectation that if someone can't draw a potted plant exactly the way it looks, on a first attempt, that person is certainly not an artist. Why is this? We would never swear off the possibility of someday playing a Beethoven minuet if we clumsily plunked out Chopsticks the first time we sat down at the piano. To forfeit the pleasure of salsa dancing because the first attempt was an uncoordinated clomp across the floor, would rarely lead to cries of, "Oh, I can't dance."

Where do we get these self-defeating notions? To help me deconstruct the cultural myth of "I can't draw," I consulted with two local artists and drawing instructors, Sandra Butler and Shan Wells. Our joint conclusion was that there is a mystification of art that is upheld in our formal educational systems and, more importantly, held inside our minds.

"I find it so interesting when adults come to me and say 'I can't draw a straight line,' like it's a God-given talent that some people get and others don't," was Sandra Butler's introductory comment.

Butler has taught drawing to many young children and observed that kids, at around 5 and 6 years old, are very willing to experiment. They will usually try anything and are open to learning how to do new things, though they have yet to possess the muscle coordination and dexterity to draw really well. She recognizes that some children are visual learners, they are the ones who "can put their pencils to their brains and think." They have yet to enter the world of "what other people think."

Shan Wells has had similar experiences and adds some perspective by reminding us "research has shown that kids stop drawing around age 10 or 11 because, at that age, they are yearning to draw realistically. If they haven't received training in those drawing skills, which is what realistic drawing is - a visible display of skill more than anything else - they give it up." Our culture certainly does value this attainment of skill and bestows the title of "artist" on anyone who can produce a likeness of the real world on paper.

Butler teaches approaches to drawing that force students to spend most of their time looking at the subject of their drawing, as opposed to looking at the drawing. She uses a blinder card that is slipped over the pencil to inhibit the drawer's ability to see what he or she is drawing on the paper. Called "blind drawing," this technique helps young artists shed their reliance on symbolic representations of things because it nurtures the ability to look at the visible "real world" instead of their symbolic inner world. Butler likens blind drawing to driving; "You'll never pass your drivers test if you are only looking at the steering wheel."

Educator Dr. Betty Edwards, a pioneer in helping people of all ages learn how to draw, advocates ways to trick the left brain into taking a vacation while learning how to draw. Her techniques teach accuracy in rendering, where a close likeness of a subject is the goal of the drawing practice. Anyone can achieve this level of skill and make realistic portrayals through a small bit of instruction and practice. Her classic book, Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, advocates a technique where the student is asked to copy a portrait that is placed upside down, so that the shapes are not recognizable as a human form. Butler says, "The upside down portrait doesn't look like a person so the left brain doesn't recognize it as such. The student can just draw lines and shapes with no words of identification coming in from the left brain. The stumbling block to drawing is the left brain telling the student what the drawing is supposed to look like."

Wells chuckles a bit as he recalls his attempts, as a drawing instructor, to get his students to look at the world in a fresh way, through a child's eyes. "On the first day of drawing class I bring my kids along and tell my students that we have some free-expression drawing experts visiting class. When the students are stuck, I ask them 'what did you like to draw as a kid try to look at the world that way and draw it.'"

All three of us agreed that the biggest reason for people believing that they cannot draw is the mystification of the art-making process. Wells says, "It comes from ignorance - when people don't understand about something, it becomes mysterious, and we fear it."

Wells adds, "There is mystery around right-brain activity and a belief in our culture that you have to be a genius to access it." Our advice: Feel the fear and draw anyway!

|