|

A trip 2½ miles beneath Hesperus

|

|

Preston Woolery, left, and Adam "Barney" Barnard head toward the King Coal Mine entrance on Tuesday. Once inside the tunnel to the cutting face, 5- and 6-foot bolts on 5-foot centers are the only things separating the men from the mountain above them./Photo by Todd Newcomer.

|

by Jeff Mannix

The tunnel leading to the cutting face of the mine is more or less 8 feet wide, the roof is a

scant 6 feet above the dirt floor, and the circuitous path goes 2 1/2 miles into and underneath a mountain that

yearns to fill the void. This is the King Coal Mine in the Hay Gulch drainage of Hesperus, just west of Durango.

The tunnel's opening is above and around a rattling, lurching, tin-shrouded conveyor terminus that looks like it

dates to the 19th century. Everything on the outside is blackened by coal dust and muck, and black runnels of water

course in deep ruts down the hillside and around the massive electric motors. After passing through the torn and

flapping curtain of thick plastic sheeting, a 15-man shift of miners, lying nearly prone on a massive steel vehicle

called a manride, begins its nine-hour day underground in the world's most dangerous working conditions.

There are no lights inside the tunnel except for the flashlight-sized lamps on the miners' helmets. The walls and

roof are within reach and are a chalk gray from a crusted dust suppressant mandated by law. The roof is studded with

nuts at the bottoms of 5- and 6-foot bolts on 5-foot centers that are the only things holding up millions of tons of

rock and dirt and certain death. It's eerie. All of the miners direct their headlamps forward and scan the walls and

roof to illuminate the path and check for anomalies in the crude surfaces that might portend their doom. The

temperature is a constant 55 to 60 degrees year round, day and night. The trip in is with the wind of a huge

circulating fan that supplies fresh air to the men and evacuates dust and gasses through return tunnels ingeniously

set up with curtains to deflect the continuous flow of forced air replacing bad with good. The trip out is against

the wind and is bitter cold, freezing wet pant legs and numbing the sinuses.

Down the length of the shaft runs a 3-inch cable that supplies 4,170 volts of electricity to the machinery that cuts,

shuttles and conveys the coal, and to the all-important roof bolting monstrosity. It runs the length of the shaft

pinned up to the wall, but when it gets to the machinery at the cutting face, it lies on the ground, and the ground

is coal mush made from the continual hosing down of the face of embedded coal being cut and removed from the bowels

of the mountain. The cable has to be pulled by hand for a number of the machines, and there isn't a man working in

the mine that hasn't been lit up from grabbing a cable that has a little nick in its casing caused by rubbing against

the sharp walls or being pinched by a 50-ton excavator. It comes with the job. The mine spends $35,000 a month in

electricity.

Willard Brown, the chief electrician, has spent 42 years underground, working in coal mines in West Virginia,

Alabama, Kentucky, Pennsylvania, Wyoming and Colorado. Willard has had two heart attacks and been advised to confine

himself to home, lift nothing heavier than 10 pounds, use oxygen full time and, damn it, retire. "I love this job,"

Willard Brown says shyly, "I can't give this up, not yet." He stands erect, looking every year of 61, blackened face

around the white outline of his safety glasses, dusted with gray powder from the walls and roof you can't avoid

brushing against underground, coveralls wet and black up to the knees, eager and appearing willing to go back into

the mine. His shift is over for the day, but he's in charge of the power, and without the power nobody works, no coal

comes out, no roofs get bolted, no money gets made. It's hard for Willard to leave. He waits until his certified

counterpart has made his rounds, found everything working, pours a cup of coffee, looks relaxed. Then Willard

changes, showers, slinks home. Mine manager "Barney" Barnard says that Willard is the best in the business.

Bob Shields is a grizzly, white-bearded 30-year veteran of the coal mines. He's a certified electrician and certified

foreman. He's one of the crew who doesn't wear a company-supplied coverall with reflective stripes. At the end of the

shift, Bob looks as if he's been dragged out of the mine, he's so dirty. He works underground, he says, because he's

a man who speaks his mind and doesn't think he could get along in the corporate world. Bob's son also works the mine,

and today is his third anniversary as a coal miner. To celebrate, Bob's son bought his father a Harley Davidson

motorcycle. Barney says that Bob Shields can do anything inside the mine and is one of his best men, one of the best

in the business. Bob II, Barney doesn't hesitate to exclaim, is following right in his father's steps: solid,

dependable, smart, careful.

|

|

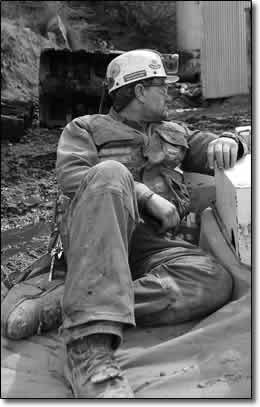

Coal miner Preston Woolery glances toward the mine entrance before the 15-man crew begins its nine-hour day in the mine./Photo by Todd Newcomer.

|

Bob Shields is a grizzly, white-bearded 30-year veteran of the coal mines. He's a certified electrician and certified

foreman. He's one of the crew who doesn't wear a company-supplied coverall with reflective stripes. At the end of the

shift, Bob looks as if he's been dragged out of the mine, he's so dirty. He works underground, he says, because he's

a man who speaks his mind and doesn't think he could get along in the corporate world. Bob's son also works the mine,

and today is his third anniversary as a coal miner. To celebrate, Bob's son bought his father a Harley Davidson

motorcycle. Barney says that Bob Shields can do anything inside the mine and is one of his best men, one of the best

in the business. Bob II, Barney doesn't hesitate to exclaim, is following right in his father's steps: solid,

dependable, smart, careful.

Asked why they work underground in that cold, dark, damp, dangerous place, the answer renders the question naive: The

money. The King Coal Mine has a fully loaded labor cost (that's with lavish benefits) of $18,000 a day, and 58 miners

are on the payroll. Clint Saudlian, of Longmont, is 6-feet, 4-inches tall, too tall, really, to be working on his

feet in such a restricted environment, so Clint operates what's called an outby utility, transporting supplies in and

out of the mine all day - $250,000 worth of supplies a month. Clint has been working underground for two years. He

likes his job and is grateful for such a well-paying job after spending a third of his life confined by the state. "I

tried working with the public, but it just didn't fit me," Clint says. "I've been operating heavy equipment all my

life. I could run a backhoe when I was 6 years old, and here underground, I can do my work and don't have to be so

politically correct as you do on the outside in other jobs." Once again, Barney says Clint is one of the best men he

has.

Chris Dorenkamp is a certified foreman and section chief. He runs the show down under. A tall, handsome man in his

40s, he is eagle-eyed yet relaxed and conversational. Chris has the intelligence and affability to be an executive in

any business he applied himself to, so why does he risk his life and health working in a coal mine? "It's never

boring," is all he need say to justify his career. Barney says that Chris is his main man, a gem of a guy who's

respected by everyone.

Dave Sornborger, from Dolores, has been a miner for 27 years. Bruce Kanuho, from Cortez, is 49 years old and has been

working underground for three years. Brothers Adam and Joshua Barnard are following their father's career path in the

coal mines. Preston Woolery, of Dolores, has been driving 100 miles a day for the past 12 years to work for King

Coal, and says he wouldn't do anything else. He's one of Barney's most trusted employees, as are Dave and Bruce, and

of course Adam and Josh.

The shift works as a team in this dark, dusty and windy cave. The machine that digs out the coal is called a miner.

It's a $2 million piece of equipment that has to be replaced after processing a million tons of coal. It weighs 50

tons and has an 8-foot wide, 25-ton circular drum on the front end with vicious spikes that literally gouge the coal

seam and deposit the debris into a hydraulically operated bin on the ground attached to a conveyor. The 30-foot-long

contraption is controlled remotely and can swivel in many directions to get turned around in such close quarters. The

miner is horribly dangerous and is responsible for many deadly "crush betweens," which Barney is proud to pronounce

has never happened at King Coal, mostly because of their strict credo - S1P2: safety first, production second; and to

having the best team in the business. Coming behind the miner is the shuttle, another multi-ton, low-slung 30-foot

vehicle that couples with the aft end of the miner. After coupling, the miner spins its cutting drum, and in about 15

seconds the shuttle is filled with tons of coal and is off to feed the conveyor that transports the product out to

the yard. After about 20 feet of cutting, the roof becomes the primary interest. It is now unsupported, and concern

over a cave-in is almost palpable. The miner retreats, and the mighty roof bolter takes his place. A heavy cross beam

is pressed up against the roof to hold it, the bolts are drilled, sometimes through hog wire sheets if the roof is

determined to be soft. The roof bolters are the lifeguards in a coal mine, working in tandem on each side of the

machine, each man with a heavy steel plate above his work station to protect him should the drilling fracture the

free-hanging roof.

Colorado is the sixth most productive coal mining state in the nation, producing 30 to 35 million tons annually.

Wyoming dwarfs all coal producing states with 100 million tons a year, and the Black Thunder Mine in the Powder River

Basin of Wyoming just produced its one-billionth ton of coal, operating continuously since 1978.The King Coal Mine

produces 550,000 tons annually, small by comparison. However, the coal it produces is prized for its low sulphur and

ash and high BTU content. Most of the King Coal product goes to cement factories in Nebraska and power plants in

California, Mexico, New Mexico and Texas.The Durango & Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad also uses King Coal.

The King Coal Mine has been operating since the 1940s, first under the ownership of the legendary Violet Smith, who

met newly authorized state mining inspectors with a double-barreled shotgun, turning them away time and again to

protect her property rights. Barney wouldn't countenance her resistance to subsequent mine safety, but it's a sure

bet that he'd like her loyalty.

|