|

Colorado River could be canary in the coal mine for global warming

|

|

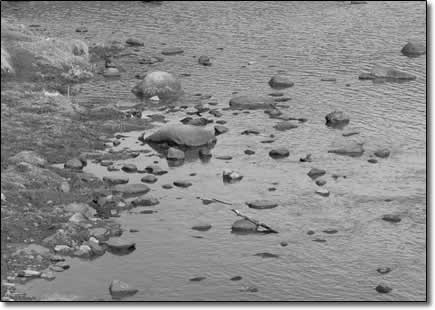

The Animas River dribbles through the Animas Valley near Durango last month. Despite a wetter than average winter, long-range computer models see a strong possibility of less moisture for the Southwest in the future, making the summer of 2002 a taste of the future./Photo by Todd Newcomer.

|

by Allen Best

An uncommonly thin snowpack in 2002 had been chased by a windy spring that came weeks early,

hot and dry. Forest fires and heat waves soon followed. Farm crops withered, suburban lawns crinkled, and foreheads

wrinkled. Water was front-page news.

Dillon Reservoir was the emblem in Colorado for that touchy, grouchy summer. Blue segued to brown, water to mud and

then dry sand.

The summer of 2005 promises to be refreshingly wet, but that summer of 2002 may portend the look and feel of Colorado

and the Southwest, as the globe warms. Aridity already rules now. Farms and cities from Nebraska to California depend

primarily upon mountain snowpacks, which supply 85 percent of the moisture in the Southwest. But with warming, there

will be less snow, and maybe less water. As is, there isn't enough to go around. Most years the Colorado River is as

dry at the Sea of Cortez.

Paradigm shift

Water in the Colorado River is allocated among the various states of the Southwest under a compact struck in 1929.

The compact was flawed in that it assumed more water in the river than has generally been the case since then. Even

the latter portions of the 20th century were unusually wet as measured against the last 1,000 years.

During this time of relative wetness, the major problem - from the perspective of politicians in Colorado - was that

California was "stealing" Colorado's unused share of water. The presumption in Colorado was that this water would

eventually be used to feed the growing cities along the Front Range and otherwise enable economic development in

Colorado.

Then, during the last five years, snowfall ebbed. This drought could be the result of normal climatic fluctuation,

but it doesn't matter. There's a new reality in the West, one crystallized by photos of Lake Powell sitting only 38

percent full.

If drought continues, Powell and its companion, Lake Mead, could empty even more. With these giant buckets sitting

empty, there is no way that Colorado and other upper-basin states can ensure California, Arizona and Nevada the water

to which the compact entitles them.

It's just possible - lots of people are talking about it - that the diversions to the farms and cities of Colorado's

Eastern Slope might be curtailed. Some ski area water supplies could also be affected. After decades of complaining

about California "stealing" Colorado's water, all this is a bit like seeing the sun come up in the west.

This drought may well be a normal climatic fluctuation. Again, it could be the result of global warming. More

alarming yet, most computer models to date - they are admittedly uncertain - see a strong possibility of less

moisture in the Southwest as a result of global warming. It's just possible that the summer of 2002 could be a

glimpse of the future.

If so, that makes the Colorado River the canary in the coal mine for global warming, in the words of Eric Kuhn

general manager of the Glenwood Springs-based Colorado River Water Conservation District. "You have a system where

the demand and supply are so close that a small change of 10 percent in the annual flow at Lee's Ferry (in Arizona,

the divide between upper and lower basin states) could cause a major disruption."

Glenn Porzak, a Boulder-based water attorney who represents most major water groups and companies in Summit County

and the Eagle Valley, says the possibility that this drought could foreshadow global warming is "in the back of

everybody's mind,"

Danger in degrees

Anyway you cut it, global warming will redefine Colorado and the Southwest. Warmer temperatures mean longer summers,

with probably drier forests more susceptible to fires. Warmer temperatures also mean more rain during winter, but

also earlier spring runoff. Instead of June, rivers will crest in May or even April.

Anecdotal evidence of such changes already exists. Dillon Reservoir during the last decade has been losing its ice

during April, not May. Peak runoff in the Colorado River below Glenwood Springs is occurring several days earlier.

Changes on the West Coast have been more profound. The peak of the annual runoff in the Sierra Nevada now comes as

much as three weeks earlier than it did in 1948.

|

|

A backhoe moves earth at the future site of the A-LP pumping station. The possibility of drier years ahead could mean more water storage projects like A-LP for Colorado./Photo by Todd Newcomer.

|

Changes on the West Coast have been more profound. The peak of the annual runoff in the Sierra Nevada now comes as

much as three weeks earlier than it did in 1948.

"The mountain ranges are essentially draining and drying earlier," said Dan Cayan, a climate researcher with the

Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, Calif.

Smaller snowpacks

Recent studies project that the heat will cause smaller snowpacks across the West. For example, the Sierra Nevada

snowpack could be reduced by as much as 50 percent by 2090. Somewhat similarly, one study forsees 30 percent less

snow in the Rockies. And runoff, in 50 to 90 years, could be coming four weeks earlier, says Kevin Trenberth, who

heads the climate change analysis unit at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder.

All of this has water managers thinking more dams for Colorado. "My attitude at this juncture is there is no such

thing as too much storage," says Porzak, whose clients include Vail Resorts.

But the River District's Kuhn points out that shorter, rainier winters will make the existing water infrastructure

less functional. He also notes that not all dam sites are equal. Lake Mead, created by Hoover Dam, loses about 1

million acre-feet of water each year to evaporation. Powell loses about half that much. Between the two, that's more

than a quarter of the water in the river in a drought year.

"The question is, 'Do we have the storage buckets in the right places?'" asks Kuhn. "My view is that you will see

additional storage, but not necessarily large, main-stem storage that evaporates."

Hotter means drier

Gerald Meehl has a professional and personal interest in this climate change. A senior scientist at Boulder's NCAR,

he was among the 120 scientists who wrote the 2001 report issued by the International Panel on Climate Change that

reported a strong consensus among scientists that the fingerprints of man had become the dominant influence on

climate change.

Meehl was reared on a dryland farm near Hudson, about 30 miles northeast of Denver. There, the winter wheat crop

depends entirely upon natural precipitation, not irrigation. Even now, wheat farming is a crap shoot. Those odds are

expected to worsen.

"The global models for quite a number of years have always projected that there would be a tendency toward drier

conditions in the summer in the mid-continental regions, which would include Colorado," he explains. "This is due to

warmer temperatures."

In other words, even if thundershowers are as frequent 30 years from now, warmer temperature will dry the soil. That

does not bode well for wheat as well as other crops in Colorado.

Of course, that's just the probability. Meehl long ago left the farm, but he still has relatives who till the soil.

Like most of us, they are interested less in long-term climate shift than in tomorrow's weather.

"My farmer uncles always make fun of me, because they ask what will happen next winter, and I always will give them a

certain range of uncertainty," reports Meehl. "They say, 'You guys never give a straight answer.'"

Still, climate change has the attention even of mainstream groups such as the Rocky Mountain Farmers Union.

John Stencel, president of the organization, which has 23,000 families in Colorado, Wyoming and New Mexico, says many

older members who can remember droughts as far back as the 1930s believe something new and different is now

occurring. "They say that weather fluctuations are greater, more severe," he reports.

Are man-caused greenhouse gases to blame? Rank-and-file members are not necessarily persuaded of the connection, but

Stencel is. "There has to be something to what a lot of scientists are saying," he says.

|