|

Silverton filmmaker documents lives lived differently

|

|

Silverton photographer, filmmaker and resident Ken Sauls pauses outside the door of his home. After years of living life on the edge and on the road in the climbing and skiing subculture of Colorado and Yosemite, he decided to buy a camera and depict the alternative lifestyles he experienced./Photo by Jared Boyd.

|

by Shawna Bethell

Sitting on a bare wood floor, elbows on his knees, photographer/filmmaker Ken Sauls leans against the wall of his Silverton home. More than 40 climbers, skiers, artists, musicians and carpenters have also congregated in the house for the 10th annual Ice Fest - a party and subculture for people living alternative lifestyles. Wood fires burn in the stoves, and the murmur of people reuniting underscores the conversation. "Of all the people I've seen come through here, some I didn't even know, some I don't remember, it's not been about climbing or skiing, it's been about people making it happen for themselves, finding their path whatever that may be," Sauls says. For Sauls, who has been questioning the American ideal of "corporate reality" since he purchased his first climbing rope at age 16, finding and following one's own path is the truest way to create a more genuine world. It is this ideal, one of living with the intention of how things are done as opposed to the goal accomplished, that brought him to filmmaking 12 years ago. But the decision to buy a camera and depict these lifestyles through film came only after years of living a life on the edge - literally. Growing up in the American middle class outside of Chicago, Sauls was brought up to follow the dream of the picket fence, the corporate job and retirement at 65. But at 16, he took a NOLS course and met ski bums and climbers who were living a decidedly different life than the one he had seen up to that point. That changed everything about how he saw the world. Later, after a year and a half at college, he sold everything but his climbing gear and moved to Boulder, then on to Telluride. For the next eight years, he lived on the road: in tree houses in Telluride, in a meat locker in Estes Park. Always on the move between Telluride, the Utah desert and Yosemite, he and his friends hitchhiked, worked construction and sold gear to scrape together cash for the next climb and met a network of people who weren't following the status quo. "I realized fairly early on that the people I was meeting, whether they were climbers or musicians, were exceptional in that they thought for themselves and created their own reality. They were creative and willing to take risks and not afraid of commitment," he laughs at his statement. "Well, not afraid of commitment except for relationships and jobs. But they were willing to commit to taking a risk and were willing to persevere." He continues to smile to himself and rubs his chin remembering. "But I knew that for me climbing was a vehicle to meet people, to go places, to have adventures." But after a while, he burned out. He got tired of being broke and dirty and started to feel that the experience was losing depth and validity. "What I saw was that climbing was becoming incredibly consumerist. People were obsessed with the tick list. They didn't care how they did something. It was like, you go and climb a 5.13 climb and now you are a 5.13 climber, but it didn't matter if you trashed the place or treated everyone around you like crap." So in the fall of 1991, Sauls and his friend Matt Buckner were on the second ascent of a line up Yosemite's Half Dome. It was their seventh night and they would be topping out the next day. Sitting on their Port-a-Ledge, they looked out across the Yosemite Valley and reminisced about the wild days. They decided it warranted a movie. But it wasn't just the climbing. They didn't want to make climbing movies. They wanted to focus on what had triggered Sauls' creative juices years before. The next winter they scraped up the money for a couple video cameras and started shooting. They focused on alternative builders, artists, musicians, skateboarders, ice climbers, big wall climbers, anybody living a lifestyle that was alternative to the status quo. "We were cognizant that we weren't going to be famous. We just felt really passionately that people needed to wake up and think about how they were living their lives. We just felt that these lunatic people we knew were the most clued in people we knew. They were independent thinkers who were able to discuss what they were thinking." Of course, as Sauls puts it, the two of them were super na`EFve. They had no idea how hard it was to make a movie. They needed a script, a story line, music, editing and money. Everything cost money. By then Buckner's passion turned to alternative building, but Sauls' passion remained with filmmaking. He was particularly passionate about continuing work on the film about big-wall climbing as an analogy for life that he and Buckner had originally begun. Through trial and error, and public showings of a clip of his own entitled "Land Beyond the Trees," the self-taught filmmaker earned a reputation of being not only a good cameraman, but someone who was able to get a camera where many could not. For four years, he did free-lance work that took him to Southeast Asia, rock climbing in Borneo, the high altitudes of Nepal, Argentina, and Norway. Last year he was one of four cameramen who summited Everest filming Toyota Global Extremes for ABC and the Outdoor Life Network.

|

|

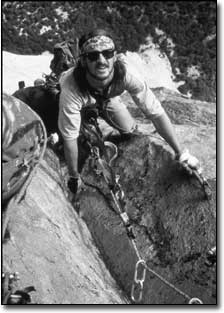

Sauls makes his way up the "Sunkist" route on El Capitan in the Yosemite Valley in 1988. Sauls' years of living the nomadic existence of a climber were the premise for his yet-to-be-released film on the big-wall climbing subculture./Photo by Clay Wadman

|

Of course, as Sauls puts it, the two of them were super na`EFve. They had no idea how hard it was to make a movie. They needed a script, a story line, music, editing and money. Everything cost money. By then Buckner's passion turned to alternative building, but Sauls' passion remained with filmmaking. He was particularly passionate about continuing work on the film about big-wall climbing as an analogy for life that he and Buckner had originally begun. Through trial and error, and public showings of a clip of his own entitled "Land Beyond the Trees," the self-taught filmmaker earned a reputation of being not only a good cameraman, but someone who was able to get a camera where many could not. For four years, he did free-lance work that took him to Southeast Asia, rock climbing in Borneo, the high altitudes of Nepal, Argentina, and Norway. Last year he was one of four cameramen who summited Everest filming Toyota Global Extremes for ABC and the Outdoor Life Network. "The greatest benefit from these jobs has been the opportunity to see what is happening in the world. I got to experience the interior of Borneo and see what is happening to our richest resource. I was able to see how other cultures see the world. Basically, I see that people all want to just get by and have a decent life. "A lot of people think I've got it made," he says. "They think it's all a vacation - shooting in these places. But it's not. It's hard work." And, it is commercial work that supports his artistic ideal. Though he's been unable to work on the big-wall film for much of the time he's been traveling, Sauls' Southwing Films is still devoted to the original vision of lifestyle, sustainable living and encouraging people to follow their dreams. And after 12 years of struggling, Saul's big-wall film is scheduled to be complete the fall of 2005.

|

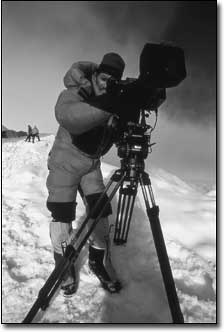

| Sauls films on the northeast

ridge of Mount Everest in May of 2003. He was

one of four cameramen who summited Everest last

year filming for ABC and the Outdoor Network./

Photo by Kent Harvey. |

"One of the foundational things I've discovered during the course of doing this work is there are a lot of people out there who talk about having a dream or a vision. But for all the people who talk about it, there's one in 10 who will actually go after that dream or vision. The bottom line that you find very quickly when you go and try to pursue your dream is that it's not easy, and it will totally kick your ass. It doesn't matter what you want to do."

Sauls lifts his hands for emphasis. Over the years he says he has resorted to every tactic he could think of, from borrowing and begging from friends, to carpentry and refinancing his home numerous times. He says he owes a huge debt of gratitude to organizations like San Juan 2000 and Region 9, which have financially supported his artistic dream. Not to mention friends and family who have supported him with advice and encouragement. "I remember the winter of 2001-02. It was a cold, dry winter in Silverton, and I was absolutely desperate, so broke. I remember going to bed done, thinking I had given it my best, and I just couldn't do it." But in the morning he'd wake up and start editing or finding funding or planning the next shoot. Something in him wouldn't let it not happen, he says, and he quotes Francis Ford Coppola saying, "It's not in the cards not to see this thing through." Now, when balancing work on his own film and his commercial work, Sauls is careful to choose projects that reflect a particular way of seeing the world. Currently, he is releasing a local film "Castle in the Clouds: Saving the Old Hundred Boarding House" about the restoration of the Old Hundred Boarding House that sits perched on the side of Galena Mountain just outside of Silverton. The project was a collaborative effort between the state and county historical societies, the BLM, the Colorado Division of Minerals and Geology, and local contractors. It depicts the hardships of the original miners who carved their place in these hardrock mountains and the effort to restore the last vestige that epitomized life on the edge. "It was a really cool project to work on," says the writer, editor, producer and cameraman of his project. "Those first miners were people who were escaping post war desperation and looking for a new life, following their dreams." In January, Sauls will begin a new project, traveling to the Bering Sea of Alaska to shoot a television series about crab fishermen for the Discovery Channel, and he is excited about the work. But his heart remains with his original plan. Eventually he wants to take his own films on the road so that he can interact with audiences personally in a multimedia forum for new ideas. The Grateful Dead, being one of his business models, were all about live performances - freaks and musicians with a vision rooted in the simple things, he says, a financially successful entity that managed to blend business and art. "I want to challenge people," says the filmmaker. "Not necessarily give them answers, but to have them ask themselves, 'Why do I climb?' or 'Why do I live the way I do? Am I pursuing what I want to pursue?' "Ultimately, the more people you get who follow their dreams - whether they succeed or not - just by virtue of living their life that way, I think it becomes a more genuine and whole world." ☯

|