|

New plan doesn’t go far enough, according to private river runners

|

|

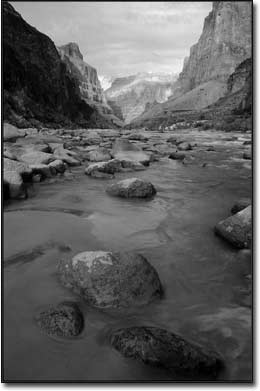

The Colorado River flows past a collection of rocks below Lava Falls, in the

Grand Canyon. A draft management plan for this famous stretch of river is

raising the hackles of some river runners who say it does not do enough to

remedy the problem of long waitlists for private boaters./Photo by Todd

Newcomer.

|

by

Amy Maestas

L

ocal whitewater enthusiasts are dismayed over the recently released draft environmental impact statement for the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon. Their biggest complaint is that it fails to equalize usage between commercial river companies and noncommercial boaters.

The draft EIS makes only minor changes to how the National Park Service allocates permits to river users, which means that noncommercial boaters who are on a years-long waiting list will likely continue to stay there in the near future. The inequality of how the Park Service doles out the permits has been and continues to be a sore spot for boaters anxious to row or paddle themselves through one of the longest stretches of navigable whitewater in the world. For many boaters, taking a back seat to commercial enterprises reeks of political wheedling.

"We have a public resource that is largely controlled by private enterprises," says Kent Ford, a Durango boater and activist. "People are waiting 15 and 20 years to get a permit and that's clearly something that has to change."

The EIS is part of the Park Service's Colorado River Management Plan, a document that will guide public usage and administration of more than 275 miles of the river. After several years of research and listening to public input, the preferred alternative chosen by Grand Canyon administrators would make only minor changes to current management. The most extensive change would reduce the number of launches per day during the summer and off-season months. Currently, the Park Service allows nine overall launches per day in the summer; it now proposes to allow only six launches per day. During the off-season, it plans to reduce overall daily launches from seven to three.

The chosen alternative also would divide the year into two six-month periods, with mixed use occurring from March through September and nonmotorized use from September through February. Currently, the split consists of nine months of mixed use with three months of nonmotorized use.

In effect, says Park Service spokeswoman Maureen Oltrogge, the longer six-month seasons will boost the number of probable total user days for both groups. For noncommercial boaters, they stand to feasibly nearly double their number of user days - from 58,000 to nearly 103,000. Commercial users would get another 2,000 user days.

The draft EIS breaks the river plan into two segments. The alternative for the segment addressing the upper part of the river was chosen, Oltrogge says, because that section has the highest total number of user-days and passengers in the summer and one of the lowest the rest of the year.

Still, for boaters like Ford - a world-class paddler who has boated the Grand Canyon nine times - the changes administrators want to make are still not addressing the unfairness of the system.

"It's not a drastic change. Commercial companies are barely going to feel a hiccup," he explains.

The inequality of the permit allocation system and the never-ending threats to the environment surrounding a river that endures 22,000 visitors each year is so heated that noncommercial boaters have formed groups to pressure the Park Service to fix the system instead of "putting wilderness up for sale," like they say the current proposal does.

"This draft does nothing but institutionalize business as usual," asserts Jo Johnson, co-director of the River Runners for Wilderness group, a river recreation advocacy group in Boulder.

The threat, Johnson says, is to the Grand Canyon's ecosystem and the quality of the wilderness experience for visitors. Johnson points to the original plan 30 years ago, which provided for phasing out the use of motorized boats on the Colorado River. Then, as now, boaters felt that the motors were deteriorating the environment and the experience for traditional rowers. The proposed changes by the Park Service reduce the number of months per year that motorized boats are allowed - from nine to six. But for Johnson and her group, that is not enough. They not only want the Park Service to ban motorized boats, but they also want the agency to transition to a nonallocated system. Such a system would require everyone who wants to run the river - commercial and non-commercial boaters alike - to apply for a permit and be chosen from applications rather than apportioning permits first to commericial businesses and then to noncommercal boaters. Right now, commercial businesses get nearly two-thirds of the permits each year, and they are essentially guaranteed these each year for several seasons.

A nonallocated system is the only way Johnson sees overcoming the growing problem.

"First, it doesn't box people into labels of commercial and noncommercial. Second, it makes it eminently fair to everyone," she said.

The concept in principle makes

4

sense, but it doesn't end up being so fair for businesses, says Andy Corra, co-owner of Four Corners Riversports in Durango.

"I understand the emotional reasons for that, but it's a hard way to run a (commercial guiding) business," Corra explained. "But at the same time, I don't think it's fair for a public resource to be used by business that makes it hard for the public to also use."

Corra, who has run the Grand six times, says he thinks the proposed changes in the draft EIS are "a move in the right direction." He believes it's better than the status quo. It pleases Corra to even see the Park Service addressing a situation that has been boiling over in river recreation communities.

It also appears, says Ford, that commercial companies are becoming more sensitive to how noncommercial boaters feel about having to wait more than 10 years to draw their permit.

"The companies are taking this threat to their businesses seriously," Ford adds. "They are stepping up and being more accommodating and friendlier to boaters while on the river. I think they are now starting to realize if they were able to be on the river only once in 15 years instead of six or seven times every year, they'd want to see changes."

Noncommercial boaters also hope the changes they are asking for make business owners understand how fundamentally unjust it is that the system caters to elite citizens who can afford a float trip costing upwards of $4,000.

Johnson says she is upset with the draft EIS and hopes public input is strong and demanding enough that the Park Service will institute more changes in the general public's favor. But since the "devil is in the details" and the public has only a chance right now to provide feedback, she's worried that the final EIS will include some surprises.

The Park Service is accepting public comments until Jan. 7, 2005. These comments will be considered and any changes will be put into a revised and final document, due in March 2005.

Local boaters remain committed to the fight, though.

"Speaking as a private boater, we need to have access to these public resources," Ford says. "I think most people have acknowledged that going into this process."

For more information on the EIS, visit the Help Desk at the Durango Public Library or log onto www.nps.gov/grca/crmp/documents/deis/index.htm.

|