|

|

|

Although on the surface it may

look idyllic, Durango, home to large Latino, white and

American Indian populations, has its fair share

of racial tension and discrimination. However, in recent

months members of various community groups as well as

Fort Lewis College,

the Durango City Council and Durango School District

9-R have stepped up efforts to address the problem. Many

say the probelm

stems from misconceptions and a lack of education and

understanding./Photo by Todd Newcomer. |

Plenty of anecdotes from minorities expose racial discrimination in

La Plata County. While these anecdotes paint a picture

of struggle, organizations working to combat the problem paint a picture

of hope.

In recent months, members of various community groups have stepped up

their efforts to address discrimination by vowing to educate residents

about the need for cultural tolerance and sensitivity. When the Rocky

Mountain Region of the U.S. Civil Rights Commission held a public hearing

in Durango last spring, residents described a multitude of discrimination

issues that eventually led commissioners to urge community leaders to

get proactive. Commissioners feel such issues are best addressed on a

local level so they left with a message: Get going.

John Dulles, director of the Civil Rights Commission, says his board

only wants to act in an advisory capacity instead of forcing out-of-area

mandates on local residents. He's hopeful that county leaders will remain

responsive.

"The discrimination issues still exist since we visited, but I had a

sense of good strong leadership in the community. There are many people

doing excellent work," Dulles says.

Achieving diversity on campus

Along with the federal commission, the Colorado Civil Rights Commission

is also providing local community leaders with guidance. The state commission

is working especially close with Fort Lewis College, a target of claims

by American Indian students. For at least a decade, these minority students

have reported to commissioners that they feel unfairly treated in a variety

of ways, including lack of available housing and bungled health care.

Because these particular issues keep arising, Wendell Pryor, director

of the state Civil Rights Commission, says he continues to have an "ongoing

interest" in achieving diversity on campus.

|

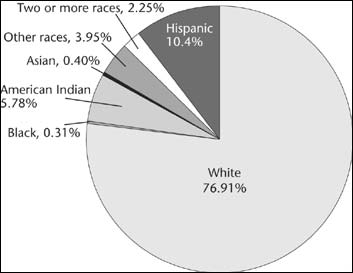

Dave Eppich, assistant to the

president at Fort

Lewis College, said the college is working on ways

to communicate better with its American Indian

students on issues of health care and

housing./Photo by Todd Newcomer. |

In recent months, state civil rights commissioners have met with college

officials to identify solutions. Dave Eppich, assistant to the president

of external affairs, says that the college is working with federal housing

agencies to identify funding to replace the dilapidated student family

housing the college demolished four years ago. At the time of the demolition,

American Indian students were upset that a housing option for the families

was being taken away. They worried they were being unreasonably locked

out.

Eppich says the students were immediately placed in single student housing

on campus - an option that remains for American Indian student families

to this day.

"Eleven families lived in single student housing during the winter semester

and of those, nine were American Indian families," Eppich says.

Eppich adds that the college recognizes the need to replace the family

housing, but receiving federal money for construction on state property

is especially cumbersome. Still, he says the college is acting at the

behest of the state commission to continue researching options.

The college is also increasing ways to communicate with American Indian

students about how to receive medical treatment in the community. The

setup is somewhat unique because American Indian students from any tribe

may attend FLC without charge. However, they are obligated to pay student

fees, one of which goes to fund the college's on-campus health-care clinic.

Eppich says in the past, there has been miscommunication about how the

clinic operates and what American Indian students are required to do

to get proper health care and be reimbursed by their tribes for any charges.

"It's largely been a matter of miscommunication," Eppich explains. "The

students come here and don't realize what they need to do in some cases,

and they end up getting caught in a bureaucratic entanglement."

This year, the college is providing American Indian students with more

and better information on how the college runs the health-care clinic

and how those operations interact with their own tribes. The increased

communication and information flow is what Eppich sees as an important

but simple fix.

"I think the most important thing to realize with discrimination issues

is that we have to understand what peoples' perceptions are," he adds. "What's

perceived is not always reality."

Teaching tolerance

Perceptions and understanding are also vital to organizations working

in area school districts. Durango School District 9-R, which some residents

often charge as not providing adequate or fair education for Hispanics

has a long checklist of actions it will or continues to take to tackle

discrimination.

Such actions include holding focus groups and youth summits, enforcing

safety, and building skills of teachers so they are better able to handle

bullying and racism. New for this school year will be the district's

Task Force on Minority Student Achievement. Deb Uroda, district public

information officer, explains that though the task force will focus primarily

on improving achievement of Hispanic students, it also will make aim

to curb racial intimidation so Hispanic students feel safe and welcome

at school.

District leaders have also embraced a working relationship with the

4 Corners Safe Schools Coalition, a nonprofit community group. The coalition

formed in 2002, shortly after a Farmington man fatally beat Fred Martinez,

a transgendered Cortez teen-ager. Martinez' identity was a key factor

in the incident and became a key issue for surrounding communities to

study. Organizations and activists pleaded with community leaders to

get involved in teaching tolerance. District leaders have also embraced a working relationship with the

4 Corners Safe Schools Coalition, a nonprofit community group. The coalition

formed in 2002, shortly after a Farmington man fatally beat Fred Martinez,

a transgendered Cortez teen-ager. Martinez' identity was a key factor

in the incident and became a key issue for surrounding communities to

study. Organizations and activists pleaded with community leaders to

get involved in teaching tolerance.

Since then, the 4 Corners Safe Schools Coalition (4cSSC) has been energetically

leading efforts to teach school students about the effects of bigotry

and harassment.

"We especially want the kids to know that in the long term, these things

can lead to violence," says Tecumseh Burnett, coalition director.

This fall, 4cSSC plans to conduct a pilot survey at Durango High School

to determine how students deal with discrimination. The coalition, Burnett

says, will use the results to instigate a series of student study 4 circles

in which students will discuss how discrimination affects themselves,

their peers and society.

In addition, Burnett says the coalition will continue to facilitate

nonviolent communication training for the community and students. This

training is based on models from the Center for Nonviolent Communication,

a global organization based on the research and solutions offered by

psychologist Marshall Rosenberg. Essentially, the center provides resources

for people to teach others how to communicate with compassion and resolve

conflicts nonviolently.

Opening minds

Community endeavors are not limited to educational institutions. Los

CompaF1eros, a local Hispanic advocacy group, continues to work on integrating

Hispanics into the larger community. Its most recent success came when

the Durango City Council agreed to adopt a resolution making the city

a "safe zone" so that legal and illegal immigrants can communicate with

the local government without fear of prejudice.

Corporal Dick Mullen, speaking for the La Plata County Sheriff's office,

says his department has not implemented any new programs to specifically

address racial profiling or intimidation at the county law level. He

only briefly stated that the sheriff's office continues to enforce and

advocate a long-term policy that prohibits such behavior and provides

measures for grievances if it does happen.

Yet, no matter how universal task forces, summits and policies are,

community leaders say that ultimately it's up to society, and especially

adults, to rid communities of discrimination.

Uroda says that addressing racism and intolerance in local schools is "never-ending." She

explains that each year school leaders deal with students from various

backgrounds and teachers with their histories and attitudes. Given that,

she says, racism won't disappear from schools until it disappears from

the community.

Pryor, director of the state's Civil Rights Commission, agrees. He says

the commission will soon approach city and county governments to enlist

their participation in the battle against racism.

That process may continue for many decades because of the rapid population

growth of La Plata County, says Sage Remington, a Southern Ute tribal

elder and activist.

Because La Plata County has a strong Hispanic heritage and two American

Indian reservations on its borders, there is a higher number of minorities

here compared to other similar small towns in the West. As more outsiders

make this area their home, they plant themselves in a milieu of cultural

significance. Some of them, Remington says, need to be active in educating

themselves and opening their minds.

"Some people bring their fortress with them when they move here," he

explains. "They don't see or take the time to understand the history

of these (minority) people, and so they keep their hearts locked and

their minds closed."

Ultimately, Burnett says, this is a similar purpose of the 4cSSC. The

only way the group can measure its success - and she believes this is

the same for other groups as well - is if they get students, parents

and community leaders involved in an ongoing and vigorous dialogue about

discrimination.

"Our main goal is to stir the pot and get that going."

|