|

Death Ride puts cyclists through 228

miles in a day

by Amy Maestas

|

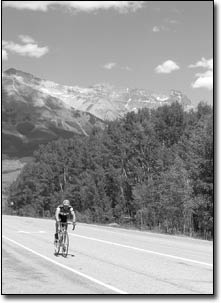

| Early in the day, Fred Hutt grunts

up the highway from Silverton toward Red Mountain

Pass./Photo by Jenna Hutt |

Last week, long before the sun had even stirred, a

group of six locals - dubbed crazy by others and even

themselves - set off to travel the famed San Juan Skyway.

Not impressive? Perhaps it isn't - if you're driving

a car. But these "crazies" were on nothing but two wheels.

The cycling enthusiasts set off to do the 228-mile loop,

starting and ending in Durango. And they took only the

day to do it. It is aptly named the "Death Ride," for

which no explanation seems necessary. In fact, there

aren't many explanations for the Death Ride, other than

it is, as originator Bob Gregorio puts it, "a group ride

amongst friends."

But it is also known in the cycling community as a sort

of "underground event." Cyclists abound in this part

of the state, especially since the terrain provides a

range of riding for a range of cycling levels. There

are also legions of organized races and events that demand

skill and fitness. These are on the surface for cyclists.

The Death Ride, in contrast, is equally, if not more,

demanding, and is talked about with regard not used for

other rides.

"It's like riding a world-class course in one day," says

rider Fred Hutt.

|

| Mike

Docherty puts one pedal in front of the next above

Telluride and en route to Lizard

Head Pass./Photo by Jenna Hutt |

This year was the 25th anniversary of the Death Ride - though

no one thought about that until the day after it was

over. You see, the ride is unofficial and so informal

that these kinds of trivial things slip by unnoticed.

The ride's casual history begins with Gregorio. In 1979,

working with the Outdoor Pursuits programs at Fort Lewis

College, Gregorio organized the 228-mile ride just for

fun. He billed it as a two-day ride, with an overnight

stop in Ouray. The cyclists pulled it off. But by the

following year, when Gregorio decided to organize the

Death Ride again, he and others significantly upped the

challenge by making it a one-day ride instead.

Why?

"Well, we were athletes looking for a greater challenge," says

Gregorio.

Over the years, the course has stayed the same, but

the dynamics have changed and new challenges have come

along. This includes everything from participants to

weather. Yet, in spite of these things, the informal

gathering of cyclists takes place each year. Because

the riders do it in one day, Gregorio says they try to

do the ride during the full moon and near the longest

day of the year. This provides longer daylight hours.

Still, there is plenty of darkness on the ride - riders

leave in the wee morning hours and return as the sun

is setting.

"This year we did it in 17 hours, but I'd say the average

is about 16 hours," Gregorio explains the day after the

infamous ride. "I'm pretty worked today. I think I lost

five pounds yesterday. No, I really did."

Although Gregorio is regarded as the founding father

of the ride, he stopped doing the rides for about 12

years during the 1990s.

"I took those years off to 'get a life,'" he says. By

this, he means he married and had children. Those priorities

took precedence over the annual Death Ride. Still, the

Death Ride went on without him. Then, last year, Gregorio

rejoined the ride he christened.

"I got a life but I still pursue my various endeavors," he

explains.

|

| On

only the second of many major passes, Fred Hutt and

Bob Gregorio work their way to the top of Molas./Photo

by Jenna Hutt |

Gregorio was back at work as a bike mechanic the day

after the Death Ride. He didn't have time to spare, but

he wasn't gloating.

During his absence, Gregorio says, more and different

people experienced the Death Ride. It scared some away,

while hooking others. Some years, the group grew to include

as many as 12 riders. But usually the number of riders

is only a handful.

"It is so classically difficult that I always knew it

would weed out a lot of people," he adds.

This year, six men and two women ventured over several

of the most difficult mountain passes in the Continental

West. Riders included Gregorio, Hutt, Rick Callies, Linda

Paris, Emily Loman and Mike Docherty.

All of them gathered for what Gregorio calls the ultimate

and only prize: common fatigue and pain. Fortunately,

they all thrive on a test of physical endurance and mental

moxie.

"The first time I did it, I wanted to see if I could

do it. The second time I did it to see if I could do

it and enjoy it," says Callies, whose second ride was

this year.

The official word from Callies is that he did, indeed,

enjoy it this year. He is also officially part of a crazy

group.

"Every time I heard people talk about doing this ride,

I thought they were crazy," he says.

This year Callies decided to do the Death Ride only

a few days before it was scheduled. The last-minute decision

paid off, mostly because this year's riders didn't engage

in a pseudo-race, he explains.

In the past, some people turned the Death Ride into

a race, where it was a daylong game of attack-and-chase.

Ultimately, this burned out everyone too quickly and

even tainted the spirit of the decades-long ride.

"This is not something that's enjoyable to be ridden

as a race," says Hutt, who has finished the ride three

out of the four times he's attempted it.

|

| Riders take advantage of

the group as they

draft their way up Dallas Divide. The six

were well into the ride but still more than

100 miles from home./Photo by Jenna Hutt |

With Gregorio back, Callies says, he thinks the Death

Ride will continue in the spirit it was born with - a

ride without pressure and pretense. Hutt agrees. In fact,

he says he rode this year because Gregorio was on board.

"Since he's the founding father, I wanted to do it with

him and do it in the fashion of a team ride," says Hutt.

All three of these riders attribute the longevity of

the ride to this prevailing approach. "Nothing is official

about this ride, which, for me, is part of the appeal," Gregorio

says, always emphasizing that it is not a race.

As the originator, he isn't interested in turning the

Death Ride into an organized event either. Neither are

its other participants. They like the anti-establishment

nature of a ride with a good reputation. Which, by the

way, is enhanced because there have never been any serious

injuries or "death."

"It just shows us that there is a crazy person born

every minute," says Callies.

|