|

Sofia van Surksum tells of recent journey to Iraq

by Jen Reeder

|

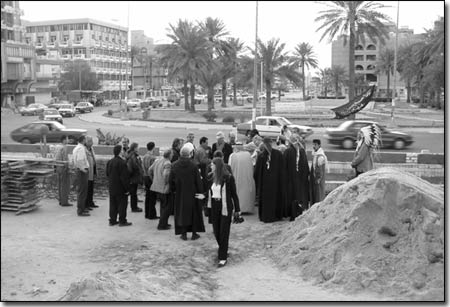

| An interfaith delegation, including

Durango’s Sofia van Surksum, prepares to plant a peace

pole in front of the National Theater in Baghdad, Iraq, on

March 20, the anniversary of the start of the war in Iraq./Courtesy

photo. |

On March 16, the day after the conclusion of this year’s

Durango Film Festival, its director, Sofia van Surksum, left for

Baghdad.

James Twyman, a filmmaker/musician who had attended the festival,

invited van Surksum to Iraq as a coordinator for a peace concert

to raise money for a children’s school. The concert was

scheduled for March 20, the one-year anniversary of the most recent

war in Iraq.

“James’ intention for this event was to have one

positive story come out on the one-year anniversary of the bombing

of Iraq,” van Surksum says.

Van Surksum flew to Amman, Jordan, where she met up with Twyman’s

group of about 10, including an Israeli Jew, a Lakota chief and

a Russian shaman.

That evening, the group learned of the bombing of a hotel in

Baghdad – the day before they were scheduled to arrive there

– but their resolve was unshaken. They all left the next

day and drove 17 hours to Baghdad with their hired Iraqi drivers.

After breezing through the border, van Surksum had her first views

of Iraq.

“I expected torn up, rural dirt roads but it was a four-lane

highway 85 better kept than some of the roads I’ve seen

here,” van Surksum says. “We were about three hours

into crossing the border when we saw our first U.S. tank blown

up on the side of the road.”

As the party continued through the desert, van Surksum noticed

all the telephone towers were knocked over. She asked the driver,

who was fluent in English, if it was the work of terrorists.

“No, it was the United States government,” he replied

matter-of-factly.

On entering Baghdad, van Surksum was again struck by the seeming

normalness of the city.

“Then we started seeing places that had been bombed, like

a four-story building that was completely bombed out,” she

says.

The group checked into a hotel only two blocks from the hotel

bombed on March 17, and walked through the neighborhood to meet

with Donna Muhearn, an Australian activist who spends half of

her year building homes and schools for Iraqi children.

“The people were very, very nice,” she says. “They’d

come out of their houses to say ‘hi’ to us.”

|

| Members of the delegation, including van

Surksum, visit a children’s school in Iraq./Courtesy

photo. |

The next day, van Surksum and Twyman headed to the Sheraton and

the Palestinian Hotel, where most foreign journalists in Iraq

stay. The hotels were surrounded for six blocks by a concrete

wall with turrets and machine guns manned by the U.S. military.

After walking through a metal detector, they entered the Sheraton

to visit different media stations and promote the peace concert

the following day. The journalists were exhausted but hospitable,

and eager to cover a positive story, she says.

While in one converted hotel room, van Surksum stepped outside

to the balcony, where a cameraman was filming. Thousands of Iraqi

men were below, protesting the U.S. occupation.

“It was a peaceful demonstration,” van Surksum stresses.

After about 45 minutes, the crowd dispersed, and van Surksum

and her companions were able to walk through the area.

“It was like nothing had happened,” she says.

But later, she was dismayed that CNN’s coverage of the

protest had a “negative spin,” claiming “Rioting

in Baghdad.”

“I’m watching what’s really happening and watching

what’s on the news, and they’re two completely different

realities,” van Surksum says.

Van Surksum says an exchange with a taxi driver that evening

not only drove home that point, but also epitomized her experience

in Iraq. She said the taxi driver asked her why “the American

government and the media demonize the Iraqi people and Muslims

to the Americans?”

Caught off guard, van Surksum said, “I don’t know

– I’m not involved in politics.”

The taxi driver replied, “Please go back and tell the American

people that we have white hearts, that we want peace. That we

have children, that we have businesses, and we have lives just

like them, and we want peace.” In the Arabic world, a “white

heart” means it is pure and that you’re good and trusted,

van Surksum explains.

She said she told the driver that Americans also have white hearts,

and he answered, “Every religion and culture has people

with white hearts and some that are stained, and those are the

ones we must love.”

Van Surksum said she tried to assure the man by telling him,

“We’re here as people and we’re here to bring

peace.”

In turn, she said he responded with the utmost gratitude, telling

them that it was “wonderful to have you visit our country

and if there is anything you need, you are my guests.”

“It was so profound,” van Surksum says. “And

that is how the whole four day experience was.”

Finally it was March 20, the war’s anniversary and day

of the peace concert. Religious leaders from all different traditions

were on hand, from Islamic Sufis to Benedictine monks, and each

led a prayer for peace, van Surksum said. On his guitar, Twyman

played songs of peace, and at the conclusion, their companion

Eliyahu McLean stood on stage in orthodox Jewish attire and addressed

the audience in Arabic.

“We are all descendants and tribes of Abraham,” he

said. “We all want peace and now we must learn how to live

in peace 85 and find commonality.”

Everyone fervently shook their heads in agreement, van Surksum

says, and then the participants planted a Peace Pole in front

of the Baghdad National Theater. The pole said “May peace

prevail on Earth” in Arabic, German and French.

“The symbol of all of us being there on that anniversary

date in a place that’s had so much atrocity to bring peace

and unity... was a very profound experience,” van Surksum

says.

The event raised $3,000 for a children’s home, a school

to be named “Peace Bird School” (“peace bird”

was chosen over “dove”) once a building can be renovated.

Because of the war, a lot of Iraqi children have lost their families,

and left with no one to care for them, they sometimes enter gangs,

van Surksum says.

Van Surksum visited a children’s school where she found

herself surrounded by kids aged 4-13 petting her long brown hair

and gaping at her pale skin and blue eyes.

“One little girl came up and hugged me and that was it!

I was hugging them all,” she says. “I had a wad of

money in my pocket and handed it to the (school’s) director

on my way out.”

The next stages of van Surksum’s time in the Mid-East involved

a trip to Jerusalem, then Egypt and Spain. She happened to be

in Israel when Sharon had the elderly leader of the Hamas assassinated.

And though little reported, “All the (Israeli) businesses

were all on strike to protest the assassination,” she says.

She was in Spain just after the terrorist attack on the train,

which turned the elections and led to the new president pulling

troops out of Iraq.

“People were celebrating in the streets,” she says.

“It was interesting for me to see the response of the Spanish

people (to the attacks): They withdrew, and they just prayed.”

Van Surksum says she is grateful to the Durango community for

understanding her need to leave so soon after the Film Festival

on the “amazing journey,” without having time to publicly

thank everyone for their help.

She says now the question is what to do with her new knowledge

of the world.

“I don’t know what to do at this point but continue

to try to be the bridge and show a different side that’s

not being portrayed in the media,” she says. “They’re

not the barbarians we make them out to be – I never felt

fear the entire time I was (in Iraq).”

She said the experience has driven home the importance of exposing

the public to all sides of an issue.

“Independent news, independent newspapers and independent

films are extraordinarily vital and important to maintaining freedom

of speech and diversity of perspectives,” van Surksum says.

“I realized that it doesn’t matter where you go or

what language...we’re all humans.”

|