|

One Day on the Maintenance of Way

by Todd Thompson

|

| James Armstrong waits outside of

the Hermosa yard for the Durango & Silverton Narrow

Gauge Railroad double-header engines to couple together

and begin the climb up to Silverton./Photo by Todd

Thompson |

It is a quiet Saturday morning at the Maintenance of

Way Shed next to the Durango and Silverton Narrow Gauge

Railroad tracks. James Armstrong arrives at 7:15 a.m.

and begins his preparations for opening day.

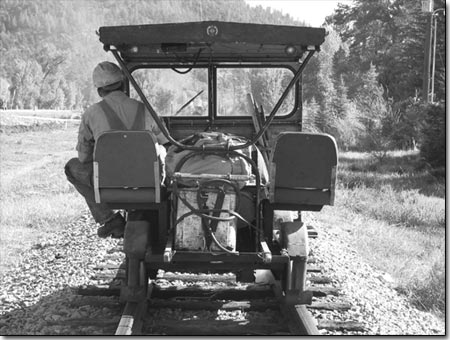

I meet him, and we head over to the corral holding four

small track cars. Locals call them “putt putt cars;”

Armstrong and the maintenance crew call them “pop

cars.” Working a hand crank and adjusting the throttle,

Armstrong finally gets the cold, two-stroke motor started.

“Pop ... pop! Pop-pop-pop ... pop!” The neighborhood

echoes as the car warms up.

I’ve got a lot of questions, but Armstrong is busy,

and conversation is difficult above the noise. Soon we

hear the train whistling its approach. He kills the motor

and hands me a hard hat and a pair of earplugs. It appears

the interview is over.

“Don’t worry,” he says, “we’ll

be able to yell at each other.”

Engine 481 roars past us, pulling its tender, a boxcar

and 14 coaches of manic, waving passengers. The year’s

first train to Silverton disappears across the bridge.

|

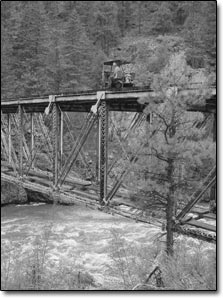

Armstrong’s inspection

and maintenance is

especially vigilant on the high bridge over the

Animas River./Photo by Todd Thompson |

Armstrong extends the lever bars, pulling and pivoting

his pop car onto the tracks. He again starts the motor,

still very loud despite the earplugs, and we load up.

He calls on the radio to indicate he’s “on

the block.” The dispatcher comes back through an

enormously loud speaker near our ears. Then the engineer

is on the radio giving his location and indicating that

he’s in possession of “437 souls.” The

car starts rolling, and we begin our trip up the Animas

Valley, two more souls on the journey.

The ride starts out rough. Armstrong figures we’re

doing 20 mph, but with the slapping around the corners

and the bouncing over the rail joints, it feels like 40.

There are no seatbelts, no handrails, no shock absorbers,

and not much room. Looking down, my feet appear to be

flying just above the gravel. It is not a smooth flight.

After some initial nervousness I settle into an uncomfortable

position leaning well toward the center of the car. A

few joggers and bikers are on the path next to the tracks.

Most wave, and all of them smile. Armstrong waves and

smiles to one and all. Everyone seems to love the putt

putt car.

Between careful negotiations of the road crossings north

of town, Armstrong bellows out our schedule and duties.

I can barely hear him, but get the idea that the train

ahead of us is so long that it will need to couple with

another engine near Hermosa for the uphill lug. We’re

to meet a number of other workers at various points along

the rails. The engines will uncouple to ride the “high

line” and cross a bridge, recouple for another climb,

and we’ll all pull into Silverton around noon. 4

“Our job,” he yells at me, “is to protect

the train. We have to watch for fires, try to put them

out, and make sure the tracks are OK.”

I’m not sure the tracks are OK the way we’re

bouncing, but I see signs of recent work on the ballast

so I gather that this is as good as it gets. As we slow

down outside of Hermosa, I realize that the loud popping

of our motor is only half the noise. The wheels shriek

and click, the drive belt squeals, and the whole car rattles

and rumbles. Armstrong kills the ignition as we come to

a stop and the silence is extraordinary.

The engines have coupled and the double header pulls

away up the grade. We ride into Hermosa yard where we

stop and meet four other workers piling into a small “gang

car.” As we head out of Hermosa, Armstrong hops

out to operate the highway crossing gate. The countdown

is on to cross the road quickly, and the track car strains

under the slight ascent.

I begin to notice how difficult the car is to drive.

A series of quick adjustments to the throttle, timing,

and fuel mixture gets the little motor revved up. Gentle

pressure on the belt drive transfers that “power”

to the wheels. As we get up to speed, the belt is fully

engaged and the driver continues to adjust the throttle

and timing levers. Somehow these all work together differently

to make the car go backwards.

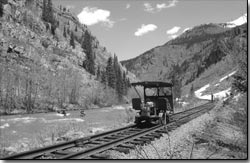

|

| Three kayakers pass a routine track

inspection as they begin their trip down the Upper

Animas./Photo by Todd Thompson |

We get up near Rockwood and wait for the two engines

to separate. As the train disappears through the cut,

we pull into the yard and come to a stop. Armstrong explains

that the train has a 5 mph speed limit over the high line,

and the track cars can’t easily be driven that slowly.

Soon the gang car pulls behind, and the crew gets out

to wait with us. The camaraderie of the men is evident.

Some have been working on the railroad for years, some

for decades. Sometimes they work together maintaining

the roadbed, bridges and drainages using the heavy equipment

parked nearby: a cutter, tamper, crane and digger. In

winter they’ll plow and blow snow. Sometimes they’ll

work together off the tracks cutting cat lines and reducing

fuel loads in the forest. Today they’re working

together as scouts and firefighters.

Armstrong tells me the risk of fire will be worst on

the steepest climbs. When the engines have to work harder,

more burning cinders are released in the exhaust, despite

the wire screens and smokestack sprayers. “If we

can’t put out the fire by hand, these guys have

300 gallons of water.”

Jeff Taylor, the road master, says that if his crew can’t

put out a fire using its tools, there’s a thousand

gallons of water and 400 feet of hose in the boxcar at

the front of the train. When the fire danger increases,

the Readiness Plan calls for a diesel engine to pull a

7,500-gallon tank car behind the train. In the most severe

conditions, it could soak the right of way before the

train comes. In an absolute emergency, the diesels could

pull the train instead of the steam engines, thus ensuring

4 that the D&SNGRR cannot be shut down again because

of fire danger, as it was in the disastrous summer of

2002. The governor of Colorado has publicly praised this

million-dollar fire readiness plan.

Soon we’re heading out of Rockwood and on to the

high line traverse. The spectacular view from this narrow

shelf cut into a cliff is what the passengers come to

see. But passengers only get to look out the side of the

train. On the putt putt car our view is an open panorama

of the tracks ahead of us and the breathtaking drop off

to the river below.

|

| Track inspector John Martinez consults

with Armstrong about the timetable during a brief

stop near Elk Park./Photo by Todd Thompson |

As we make our way forward, the river slowly rises up

to meet us and we are soon crossing the bridge into the

upper Animas canyon. The river is churning violently,

seemingly impassable, but farther upriver some kayakers

and rafters are braving the boil. We catch up to the train

where the engines are recoupling for the next climb. The

brakemen are out inspecting the undercarriage and wheels.

Hand signals are passed back and forth along the line,

and the train is soon under way again. We stop to inspect

the water tank and Armstrong explains that both engines

refilled their tenders here to take on enough water to

get to Silverton. “Sometimes in the winter, we have

to burn diesel-soaked ropes under the pipe to keep the

water from freezing.”

Not far up, the train has made an unscheduled stop. Armstrong

radios the gang car to stop at a certain mile marker.

One of the engineers radios the dispatcher to report a

faulty boiler injector. A huge plume of smoke and steam

rises ahead of us. Evidently the engineer is satisfied,

and the train resumes its climb. Then the conductor is

on the radio reporting a “strong smell of wood smoke.”

Sure enough, when we get to where the engines stopped,

there is a small fire burning beside the tracks. Armstrong

rushes out with a shovel to begin containment. By the

time the gang car pulls up, the fire has spread to a 5-foot

diameter. Road Master Taylor starts up the water pump,

and his crew quickly extinguishes the blaze.

|

| Inspecting tracks, ties,

ballast, tanks and drainage features requires a lot

of footwork./Photo by Todd Thompson |

Up near Elk Park, we meet Track Inspector John Martinez,

who is waiting for us to pass. Martinez has been working

for the railroad for 41 years. He came up ahead of the

train to make sure the tracks were safe and to take notes

on the rough spots. “I’ve seen a lot of changes

on the road, for sure,” he says, “but we still

do about the same thing.”

In the final length of canyon before Silverton, Armstrong

points out a new section of roadbed. “We had a 5BD-foot

rock come off the mountain in a landslide,” he said.

“It blew out the tracks. We repaired this about

two weeks ago.”

By the time we arrive in Silverton, the train has disgorged

its passengers, and we can hear the brass band playing

on Blair Street. The mood is festive with Victorian dress

in abundance.

But for Armstrong, this is an opportunity to catch up

on the maintenance of his track car. After lunch, the

train passes by and Armstrong pulls his car back onto

the tracks for the long putt putt home.

|