W e decided to stop by Patzcuaro

at the last minute. My boyfriend and I were sitting in an

outdoor cafe in the university town of Morelia, enjoying our

daily dose of guacamole and flipping through our guidebook

for Mexico. The village of Patzcuaro was between us and the

coast. Why not stop by? The pictures of fishermen wielding

beautiful nets in the town's mountain lake looked cool.

But we didn't get to see the trademark fishing nets, because Patzcuaro was

in the throes of a celebration that happens only every 100

years.

Oblivious, we wandered through the streets of Patzcuaro looking

for a cheap hotel. We noticed that the bright banners and

the plaza full of musicians and vendors did  seem

festive, but Mexico itself is festive, so nothing seemed too

unusual. The hotel was sedate, the owner slow to answer our

ring for service. He mentioned something about the Virgin

of Health, but he was mumbling so we didn't really pay attention.

seem

festive, but Mexico itself is festive, so nothing seemed too

unusual. The hotel was sedate, the owner slow to answer our

ring for service. He mentioned something about the Virgin

of Health, but he was mumbling so we didn't really pay attention.

We emerged from the

squalid hotel back into the plaza and penetrated the crowds to

discover a massive "sand painting" project under way. People of all

ages were carefully using stencils to create bright art that

extended along the peripheral sidewalk of the main plaza. The

material they were using was actually not sand, but dyed sawdust

that formed a colorful chain of intricate flowers and brilliant

suns.

We watched the

meticulous precision of the artists until a noisy procession caught

our eye. Musicians and singers were pouring down a steep hill

toward us, while flanking a flatbed truck carrying a crucifix and a

bloody Christ. When the procession had finished its

circumnavigation of the plaza, we headed up the hill from where it

had come.

To our astonishment, we

found a full-scale town picnic under way, with every family eating

identical boxed lunches. We bypassed the long lines for the free

food, though not without employees of the sponsors calling after us

in English, "Drink Pepsi!" and giggling.

We wandered over to the

aging church, La Basilica de Nuestra Se`F1ora de la Salud, which

was adorned with powder blue and white streamers branching out from

its roof. Inside, another brass band was playing as hordes of

worshippers bowed to a small figurine about a foot high, perched in

a glass case above the altar. This was Maria herself, La Virgen de

la Salud. She was made from a corncob and honey paste by 16th

century Tarascan Indians and was still revered on January 20, 2000,

the day of her centennial celebration.

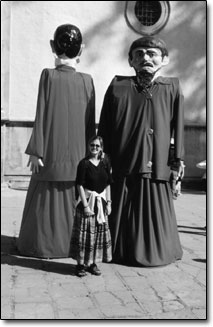

At another plaza, which

commemorated the death of a female revolutionary by firing squad, a

band was blowing itself red in the face as children played with

plastic airplanes and helium balloons. Strange "marionettes" twice

as tall as humans danced into sight with the string band that

followed them. One figure, half the height of the others, was

manned by a small boy who paused briefly to stare at the gringos

staring at him.

By this time we'd

started to catch on that this was a special day, so we fueled up

with a good dinner (graced, of course, by guacamole and Negra

Modelos) and reemerged to find night had crowded the plaza with

thousands of townspeople. We joined the expectant mob and I struck

up a conversation with the young woman next to me. What were we

waiting for? The appearance of the Virgin of Health. I asked if

this event was celebrated every year, and she snorted at my

ignorance, protesting, "No, no! Cada cien a`F1os" every 100 years.

What timing! When the Virgin finally arrived, led by a procession

of clergymen, I couldn't help joining in the vehement chorus of

"Maria! Maria! Rah Rah Rah!"

Fists in the air, the

locals continued their cheers as the Virgin was transported over

the lovely sidewalk paintings. Like Navajo sand paintings, this art

was created to be destroyed, as a testament of devotion. Elaborate

strands of fireworks exploded alongside Maria as she slowly

traversed the plaza. When she headed back up the hill toward her

church, local boys set off fireworks that shot like missiles

towards the sky, and Bryan and I noticed the moon wasn't full, as

it had been the night before. The celebration was coinciding with a

full lunar eclipse!

We joined the town as it

headed up the hill after Maria. The celebration peaked as we all

watched the tiny Madonna returned to her glass case, not to be

touched again for another 100 years.

There was more music and

cheering and fireworks as the celebration wound down. Women near

the church doors ladled out free cups of scalding fruit cider to

warm the families on their walk home. We cautiously sipped at the

liquid and watched the moon disappear. Local people resented

questions about the festival being connected to the eclipse; the

day was all about Maria, and the moon should not detract from her.

But while adults ignored the moon, the children holding their hands

couldn't walk straight they couldn't help staring up at the

phenomenon overhead.

This crazy experience

cemented my love for Mexico. Since then, Cinco de Mayo has become

more than an excuse to drink Mexican beer and tequila on May 5.

It's a day to remember how much Mexico kicks ass.

Jen Reeder