|

Indigent are most likely to get sick or injured

but rarely have insurance

by Will Sands

|

| An ambulance waits for its next

assignment outside Mercy Medical Center on Tuesday. Many people

without access to health care or without insurance end up

in Mercy’s emergency room as a last resort./Photo by

Todd Newcomer. |

Two years ago, Bruce Deile was diagnosed with Lyme disease during

a stint in Santa Rosa, Calif. At the time, he was given a three-week

course of antibiotics to treat the disease, but according to Deile,

“it didn’t seem to kill the infection.” The

38-year-old said that the disease is currently inflaming his brain

and spinal cord and, if left untreated, could paralyze or kill

him.

“After being diagnosed, I traveled to seven different states

and can’t get the intravenous antibiotics that the National

Institutes of Health say bring full recovery,” Deile noted.

Deile said he believes he can’t get the medicine in large

part because he is homeless, has been for the last six years and

can’t afford the expensive treatment. Deile’s quest

for health care arrived in Durango two months ago, joining numerous

others without housing or health insurance who face a steep path

to recovery. This picture may worsen before it improves.

John Gamble, Volunteers of America division director and supervisor

of the Durango Community Shelter and the Southwest Safehouse,

said that the homeless population faces a doubly hard health picture.

First, they are often more susceptible to health problems.

“There’s a vulnerability in the sense that you’re

often living in the street, your nutrition is less favorable and

in the case of some homeless people, your lifestyle choices are

less favorable,” Gamble said. “There are people who

every winter live in stick and canvas lean-tos in the hills, and

those people are vulnerable.”

Second, these people who are most likely to get sick or encounter

health problems are also least likely to have health insurance

coverage.

“The lack of access to health care for low income and homeless

people is really a reflection of a growing national problem,”

Gamble said. “Durango is full of employers who don’t

supply health insurance. At how many hundreds of dollars a month

does it become feasible for a homeless person to even think about

having health coverage?”

The net effect is a situation that spirals downward to a disastrous

end, according to Gamble and Teresa DeGuelle, program manager

for the VOA Community Shelter.

“One of the biggest issues is that these people may fall

ill, but they don’t get treated and it spirals into a more

serious condition,” DeGuelle said.

Gamble added, “You end up having folks who may delay access

to health care for one reason or another and they’ll wait

until they get sick and go to the emergency room. And we all know

that the emergency room is the most expensive health care you

can pay for.”

And while the common perception of the homeless person is of

a male drifter with a substance-abuse problem, Gamble said that

Durango’s homeless population does not fit the stereotype.

Instead he pointed to a large number of local individuals and

families who have fallen on hard times. Deile also contrasts the

stereotype and is proud of the fact that he has been clean and

sober since 1985, long before he became homeless.

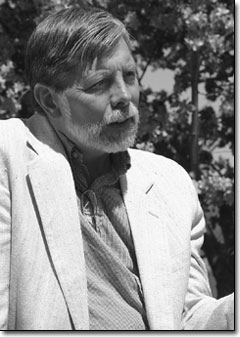

|

John Gamble, of the Volunteers of America

Community Shelter and the Southwest Safehouse, talks about

the state of health care for the homeless. He said problems

with health care access also impact low- and middle-income

segments of the local population./Photo by Todd Newcomer. |

Gamble also commented that 40 percent of Community Shelter residents

are women and children, and that all of the residents of the Southwest

Safehouse are women and children. With these factors in mind,

he said that the lack of health-care access is particularly upsetting.

“We have a large number of children in this community with

no access to health care and that’s so wrong,” Gamble

said.

He added that health care access may be visibly difficult for

the local homeless population but also impacts low- and middle-income

segments of the local population. “I think it’s important

to recognize that this is a problem demonstrated in the homeless

community, but experienced by working families all over this city,

state and nation,” he said.

Despite an apparently bleak health-care future for these segments

of the local population, Gamble said that Durango does have an

upside. Mercy Medical Center’s open-door policy does offer

some hope.

“I can’t say that I’m aware of people who are

homeless and dying on the streets,” he said. “The

medical safety net in this community is Mercy. When all else fails,

they will pick up the pieces.”

David Bruzzese, spokesman for 4 Mercy Medical Center, commented,

“We’re the safety net for everyone, homeless or not.

If you can’t afford health insurance, it doesn’t matter

to us. We serve everyone regardless of their ability to pay.”

To this end, Mercy wrote off $3.9 million in unreimbursed Medicaid

and Indigent Care costs during the 2003 fiscal year.

“What distinguishes us is, we are open 24 hours a day and

care for everyone who comes through our doors regardless of their

ability to pay,” Bruzzese said.

The one caveat is that the care is only for people who come through

the emergency room doors with an immediate life-threatening condition;

there are no provisions at Mercy for indigent primary care. Three

weeks ago, Diele went to the Mercy emergency room seeking treatment

for complications from his Lyme disease. At that time, he did

not receive the intravenous antibiotics he says are necessary.

“I’ve gone to the emergency room most recently here

in Durango because of the neurological manifestation of the disease,”

he said. “I’m told that Lyme disease is a chronic

condition and that they’re not obligated to treat it because

it isn’t acute. I’ve been told I’m only qualified

for the cheap treatment.”

Bruzzese said that Mercy is not a primary care provider and that

often makes the emergency room the only option for people like

Deile. “We don’t employ primary care physicians, so

for most people who can’t afford primary care, the emergency

room becomes their last option,” he said.

Still, Bruzzese said that Mercy and its employees deserve credit

for the service they provide to those in need. “It’s

not only Mercy as an organization that supports the community,

it’s the care providers that make sacrifices and help people

heal and repair their bodies and improve their well being and

condition in life,” he said.

Although Gamble wholeheartedly agreed that Mercy is providing

an invaluable service to the community at large, he said that

more is needed. One cooperative step between the VOA and Mercy

that has been successful is the Community Shelter’s “Medical

Respite Bed” program, he said. Over the years, the shelter

has helped homeless people with everything from broken bones to

Lou Gehrig’s disease recover. In 2002, the program saw more

than 500 user nights. Last year, it had more than 250 nights.

“Mercy realistically can’t discharge a seriously

ill person into a situation where there is not care,” Gamble

said noting that the “Medical Respite Bed” helps fill

that void.

“It costs us about $25 a night to have someone in that

bed,” Gamble continued. “I don’t think anyone

can get out of the door of the hospital for less than $1,000 a

night. With this bed, we’ve been able to save enormous amounts

of money for the community. It’s been a very successful

partnership.”

As a further solution to the problem, DeGuelle said it would

be nice to see the return of a community clinic to Durango. “I

think a community clinic that was on a straight sliding scale

would be very beneficial for everyone here,” she said.

And Gamble said that primary care providers could also help lend

a hand to local people in need. “We realize that you can’t

go to the well too often,” he said. “But if a medical

office could see one person a month or some other modest level

of commitment, that could help to address the problem.”

Still, more global solutions are required not just for the homeless

but for everyone who struggles with the expense of health care,

said Gamble. “The final sad commentary is that the wealthiest

nation in the country spends more than any other country in the

world on health care and yet we have the worst access to health

care,” he said. “There is something evidently wrong

with this picture.”

As evidence, Deile said he is seeing his search for health care

go nowhere. He considered travelling to the East Coast in hopes

of finding the remedy, but travel is becoming harder. Instead

he is resolving to accept the worst-case scenario. “It’s

gone on so long,” he concluded. “It seems like it’s

the reality that treatment is not going to be available.”

|